***You can purchase a book in paperback or on Kindle on observing lessons and coaching, or a 90-minute online workshop on supporting teacher change that you can share with colleagues at a CPD event or departmental meeting***

- Diagnosis

- Evidence

- Part 1: My lesson observation template

- Part 2: Format of the coaching session

- 1. I thank the teacher for letting me watch their lesson

- 2. I draw the teacher’s attention to the phases of the lesson that I watched

- 3. I ask the teacher to tell me the good things they did during the time I was in the lesson, and why they did them

- 4. I prompt praise

- 5. Diagnosis, Hypothesis, Evidence

- 6. We discuss actions we can take to solve the problem

- 7. We plan for an upcoming lesson

- 8. We rehearse

- Conclusion

- Want to know more?

- Implementation planning

- Book and 90-minute online workshop

Whether it is part of a formal coaching programme, high-stakes performance management, or within a culture of lesson drop-ins, observing lessons and giving feedback is a universal feature of school life.

Diagnosis

You are observing a lesson:

- How do you decide what to look for?

- What sorts of things do you write down?

You are giving feedback:

- How do you structure the conversation?

- How do you support your colleague to make change?

Evidence

Teaching is hard. My favourite quote to encapsulate the complexity of the job teachers do comes from Lee Shulman in The Wisdom of Practice:

After 30 years of doing such work, I have concluded that classroom teaching … is perhaps the most complex, most challenging, and most demanding, subtle, nuanced, and frightening activity that our species has ever invented … The only time a physician could possibly encounter a situation of comparable complexity would be in the emergency room of a hospital during or after a natural disaster.

In this short video, Dylan Wiliam puts a positive spin on this challenge:

At one time, André Previn was the best-paid film-score composer in Hollywood and one day, he just walked out of his office and quit. People said ‘why did you quit this amazing job?’ And he said – because I wasn’t scared any more. Every day he was going into his office knowing his job held no challenge for him.

This is something you are never going to have to worry about.

This job you’re doing is so hard that one lifetime isn’t enough to master it. So every single one of you needs to accept the commitment to carry on improving our practice until we retire or die. That is the deal.

Those of us lucky enough to help support our colleagues to improve have a duty to do so to the best of our abilities, using all of the best evidence avaialable.

I have been doing some version of coaching teachers for over 15 years. The problem is that I was pretty rubbish at it for many years. I would observe a colleague teach, make vague notes, and then give meaningless, unactionable feedback like: You need to work on your pace.

Terrible.

Over the last few years, I have tried hard to improve at observing lessons and delivering the subsequent coaching sessions. Any improvements I have made have been down to four people: Adam Boxer, Josh Goodrich, Sarah Cottinghatt, and Ollie Lovell. At the end of this section, I will link to the specific aspects of their work that have helped form my process.

Using lessons from these three greats, I have built a template I fill in in each lesson I observe and then use to support each coaching session I deliver. I will walk you through it, in two parts:

- What I put in each section during a lesson observation

- How this supports a structured coaching session

In each case, I will provide a concrete example from a teacher I coached, Tom so you can follow the journey from start to finish. I will also add examples from other teachers I have been lucky to work with so you can see the variety of things that could happen.

Part 1: My lesson observation template

High-level overview

Here are the seven sections of my template:

- Context

- Lesson commentary

- Specific praise to prompt

- Hypothesis

- Critical evidence

- Diagnostic questions

- Suggested action

At the top of my template, I have the following image of the Six Fundamental Problems of Teaching from Josh Goodrich’s Responsive Coaching book, as they help me identify specific praise and form my hypothesis.

Here is a Google Doc version of my template to download if it is useful.

The technology

I have this template on an Evernote doc. I am a big fan of Evernote as it allows me to easily import photos into the template (as we will see, photos play a big part in my observation and coaching process), and I find the search function powerful.

However, this template could just as easily be used with any note-taking app or simply with pen and paper.

I also use the voice recorder on my phone to capture audio from the lesson.

Finally, I offer the teachers I work with the opportunity to have their lesson videoed. In this case, I use the camera on my iPhone, mounted on a tripod at the back of the lesson, with a Bluetooth clip-on mic attached to the teacher.

1. Context

I write anything I have been told in advance that may be relevant to the lesson or the teacher taking part in the coaching. Examples include:

- How experienced the teacher is

- The set / prior achievement level of the class

- Where in the curriculum this current lesson sits

- Any specific area of their practice or the lesson they want me to pay particular attention to

Example from coaching Tom

- 8 years of experience

- Middle-set Year 9

- Topic: Simple interest.

- This was the second in a series of lessons on maths and money.

- Tom has not given any particular focus

- I will watch the first 30 minutes of the lesson

2. Lesson commentrary

As soon as I enter the room, I take a photo of the teacher’s board. I find photos the most useful medium for reflecting on the lesson, and—as we shall see—they are powerful as a frame of reference or catalyst for discussion in the Specific praise and Diagnosis part of the coaching session. I will continue to take photos of the board throughout the lesson.

For the same reasons, if a teacher is about to begin an explanation, give some instructions, or orchestrate some questions and responses, I will often hit record on my phone’s audio recorder.

I also keep a brief timeline of the teacher’s and students’ activities. Again, this is useful for me when reflecting on the lesson and can also provide objective evidence in the coaching session.

Example from coaching Tom

Time-line:

11:15 – first bell rings, Do Now on the board

11:22 – all students in the room, door closed

11:27 – teacher begins going through the Do Now

“Everyone I saw remembered that anything to the power of 0 is 1”

11:36 – teacher finishes going through the Do Now

…

Example from another teacher

10:28 – students attempt the We Do in their books

10:30 – students given 5 questions to complete in their books

10:35 – students given a worksheet to do independently

3. Specific praise to prompt

Throughout the lesson, I look for specific things the teacher is doing well. Specific is the key here. So, not things like: I liked your questioning. Instead, it is: I liked the question you asked Isaac about the first step when factorising a quadratic. The more specific, the more meaningful, and if supported by evidence such as a photo or a quote, even better.

I aim to find two or three specific things to praise the teacher for, and never more than five because the effect of each is diluted. Josh’s diagram at the top of my template helps here, giving a hierarchical checklist I can use.

Example from coaching Tom

- The use of mini-whiteboards throughout the Do Now was impressive as it enabled the teacher to check the understanding and effort of every student instead of hearing from just one or two.

- There was a lovely moment when the teacher gave an explanation and then checked whether a boy at the back of the class had been listening (he hadn’t). The teacher reinforced the importance of listening, asked another student, returned to the boy and got him to repeat what they said, and then (this was my favourite bit) returned to the boy a few minutes later to check if he was still listening (he was).

I made a note of these in the Specific praise to prompt section of my template:

- Mini-whiteboards in the Do Now for mass participation

- Conversation with Reece about him not listening, returning to him to check again

We will see more examples of specific praise, along with how this praise is used, in the coaching section below.

4. Hypothesis

This is the fun bit. I try to spot something in the lesson that isn’t going as well as it could be, or as well as the teacher thinks it is. As with the praise section, I find Josh’s diagram on the Six Fundamental Problems of Teaching beneficial here as it gives me an ordered checklist to work through:

- Is the lesson pitched correctly? Yes.

- Does the teacher have the students’ attention? I’m not sure…

Then, I need to form a testable hypothesis. The hypothesis must be framed in such a way that I can gather objective evidence within the lesson to either support or refute it.

Where possible, I form multiple hypotheses. This allows for the possibility of one or more hypotheses being refuted by the evidence, or allows me to choose which one is the most impactful for the teacher to focus on in the coaching session.

Example from coaching Tom

Because you have asked the students to show you three answers simultaneously on their mini-whiteboards, you will miss some wrong answers.

Examples from other teachers:

- Because you have not checked for listening, some students have not heard your explanation

- Because of your choice of example, some students will be unable to answer this question

- Because you have not assessed prerequisite knowledge, some students will get stuck on the We Do

- Because you have not addressed the fact that Sophie called out an answer, Sophie will call out another answer soon

- Because you have not moved on when student responses indicate their understanding is secure, your Do Now will take longer than the planned 10 minutes

- Because you have not given instructions on how to structure the Turn and Talk, some students will not contribute to the discussion

5. Critical evidence

I then spend the next few minutes gathering evidence to support or refute my hypothesis. This evidence must be clear and objective. Examples of good critical evidence include:

- Photos

- Video

- Audio recording

- Timings

- Data – eg the number of students who got a question wrong

- Direct quotes from students or teachers

I hope my evidence-gathering leads me to conclude that my hypothesis is wrong, because that means that students are learning more than I feared. If my hypothesis is wrong, I must ditch it and form a new hypothesis despite my belief that the teacher could do something better.

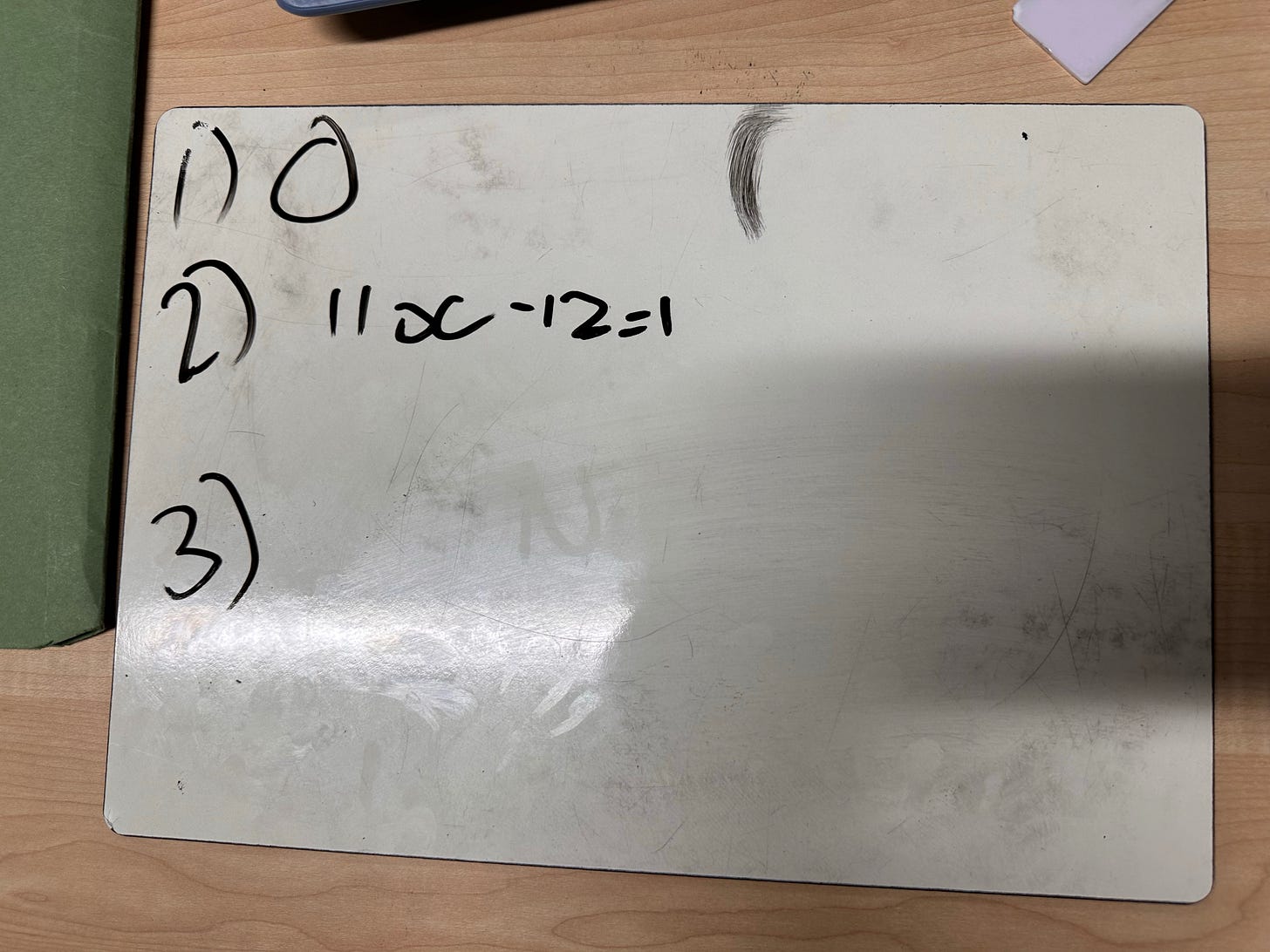

Example from coaching Tom

Quote from teacher referring to the answer to Q1: Everyone I saw remembered that anything to the power of 0 is 1

Photos of four students’ mini-whiteboards from the back row indicating that several students have got this question wrong or left it out:

Examples from other teachers

- Audio recording of a teacher saying the name of the student first and then asking the question when using Cold Call:

2. Time taken to review various questions in the Do Now:

- Q1 where all students had the correct answer: 6 minutes

- Q4 where only 4 students had the correct answer: 2 minutes

3. Student responses when asked what word means “The order in which we multiply does not matter”:

- Inverse

- Community

- Can’t remember

- Begins with T

- Commutative

4. Data on the number of students who got the correct answer to a question: 5 out of 30

6. Diagnostic questions

These are questions I use in the coaching session to draw the teacher’s attention and support their recollection of the phase of the lesson related to the hypothesis and critical evidence.

There are two types of diagnostic questions I use:

- Situational questions – these prompt the teacher to describe the phase of the lesson

- Tell me about your Do Now

- Talk me through your explanation

- Awareness questions – these direct teachers to think about a specific aspect of the situation

- How did you check for understanding during your Do Now?

- How many students were listening to your explananation?

I typically write these diagnostic questions after I have come out of the lesson when I am planning the coaching session.

Example from coaching Tom

- Talk me through this phase of the lesson (I showed a picture of the Do Now)

- Describe how you collected your students’ responses to the Do Now.

- How many students got Question 1 wrong?

Examples from other teachers

- Talk me through how you asked students to participate in this phase of the lesson?

- What specific instructions did you give them?

- How many students contributed to the Turn and Talk?

- How did you go through the answers to the Do Now?

- How did you choose to allocate your time between the questions?

- Which question do you think you spent the most time going through?

- How long do you think you took going through this question?

- Talk me through your choice of example here

- When do students first meet this concept in primary school?

- How many students could have answered this question correctly before you explained it?

- Talk me through how you explained this procedure?

- How many words do you think you used?

- How long do you think the explanation took?

We will see how diagnostic questions are used in the coaching session below.

7. Suggested actions

The final part of our lesson template outlines the actions the teacher could take to address our discussed issue.

As we will see below, the suggested actions can come from either the teacher or the coach, or be a collaborative effort. However, it is always worth planning a suggested action in case the teacher cannot find a suitable solution.

Example from coaching Tom

Reduce the amount of data on the mini-whiteboards by asking students to copy only the final answer to Question 1

Examples from other teachers

- Ask checking for listening questions during the I Do

- Plan a specific phase of the lesson to assess prerequisite knowledge

- Structure the Turn and Talk so students know how talks first and when to switch from talking to listening

- Give students time to write down their answers before you Cold Call

- Count our 3 seconds after a student has given a response to allow students time to process the answer

We will see how the suggested action plays out in the coaching session below.

Part 2: Format of the coaching session

In his book, Responsive Coaching, Josh Goodrich outlines three external reasons why teacher change is hard:

- Schools are time-pressured, stressful environments

- Schools are filled with ‘noise’ and conflicting messages

- Professional development often lacks personalisation

The coaching session must address these issues by:

- Not being rushed – I insist on at least 30 minutes for a coaching session, ideally longer

- Just focus on one action step – two or more things to work on reduces the chance of successful implementation and also makes it impossible to determine which has had an impact

- It is my observation of the teacher that determines what we will work on, not some predetermined whole-school focus

Josh goes on to identify five internal reasons why teacher change is hard:

- Awareness: Can we see what we are aiming to change?

- Insights: Do we have an accurate understanding of how learning works?

- Goals: Do we prioritise aiming to change our practice?

- Steps: Do we have the technical knowledge to control an aspect of our classroom?

- Habits: Do we use the right techniques at the right times in the heat of the moment?

Again, the coaching session must address these issues. Josh puts this better than I ever could:

Let’s see how the notes we have taken in the lesson, together with our awareness of the challenges of teacher change, come together in the coaching session:

1. I thank the teacher for letting me watch their lesson

Watching a colleague teach is a privilege, and for many teachers, it is a big deal that they will have felt anxious about. It is important to begin the coaching session by acknowledging your gratitude.

2. I draw the teacher’s attention to the phases of the lesson that I watched

Teachers have a million things on their minds when in the classroom, so I must make them aware of the phases of the lesson I was present for. Once again, images play a key role here. I will show them a picture of the board from when I first entered their classroom, and then a picture of the board when I left. These frames of reference immediately put the teacher back into the lesson, setting them up for the discussion that follows.

3. I ask the teacher to tell me the good things they did during the time I was in the lesson, and why they did them

Much like the diagnosis phase that follows, I want to allow the teacher to identify the strong aspects of their practice. This gives me key information about the strength of their mental models. Are they aware of what they do? Do they have insight as to why they do it?

As well as a lack of awareness or insght, many teachers fail to respond here due to modesty. So I don’t push too hard for a response. But I always allocate a few minutes to give the teacher time to think.

4. I prompt praise

I will then share anything from the Specific praise to prompt section that the teacher has not picked up on. I do this one point at a time. I describe the action they did or decision they made that I liked – such as the question to Isaac about factorising quadratics – but then ask them to tell me why they did it.

Prompting praise, as opposed to simply giving praise, serves four purposes:

- It continues the positive start to the coaching session

- It reveals the strength of the teacher’s mental models – are they aware of why they do the things they do, do they have insight as to why they do them?

- It makes the praise more potent and meaningful as it is part of a conversation as opposed to a monologue

- It engages them in the coaching session from the very beginning – instead of receiving praise, they are actively involved in analysing it.

If the teacher is initially unable to tell me why they do the good things they do, then I will keep probing. If they still can’t, that suggests their mental model is not where it needs to be, so I will need to be more directive in my support and recommendations for the remainder of the coaching session.

Example from Tom’s lesson

- I liked how you used mini-whiteboards in the Do Now. Why choose this particular means of participation versus, say, Cold Calling?

- I loved your exchange with Reece, in which you challenged him for not listening and then returned to him a few minutes later. Talk me through your decision-making here.

Examples from other teachers

- I liked how you have your worked example visible on your board while students are working on the You Do. Why do that?

- I love how you have a visible timer during the Do Now. Why choose to use that?

- I really liked how you went straight to Callum when you set the students off on their worksheets. What informed that decision?

- I really enjoyed the questions you asked students during the I Do. What type of questions were they, and why did you choose to ask them during this phase of the lesson?

- I thought your decision to ask Hollie to move seats when you did was the right one. Please talk me through your decision-making process here.

- I loved the way you initiated a Turn and Talk following the first mini-whiteboard check. Why do one at this stage of the lesson?

- Your use of Cold Call is so consistent. Why do you always put the name at the end when doing a Cold Call?

5. Diagnosis, Hypothesis, Evidence

Next, I draw the teacher’s attention to the phase of the lesson about which I have formed my hypothesis. Once again, a photo is really helpful here as it provides the frame of reference and catalyst for recall.

Returning to Josh Goodrich’s five internal factors, I need to determine:

- Awareness: How aware is the teacher of the issue?

- Insight: How much insight do they have as to why the issue has occurred?

- Goals: Can they identify a big-picture solution?

- Steps: Can they identify the steps needed to get to the solution?

- Habits: Can they identify the habits they will need to build to regularly follow these steps in the classroom?

In other words, how strong are their mental models?

I begin by asking the teacher a situational question. Something like: Talk me through this phase of the lesson.

If the teacher diagnoses the problem immediately, we can immediately start thinking about goals and steps. I may not even need to share my hypothesis and the critical evidence I have gathered to support it.

However, if they simply describe the events, I will ask an awareness question. Something like: How did you check for understanding? Or even more directly: How many students got the answer correct?

With each new question, I am guiding the teacher towards the issue, and learning about the strength of their mental models.

If the awareness questions still do not prompt the teacher to realise the issue, I will tell them, using my hypothesis and the critical evidence I have gathered to support my case.

This is the most critical and potentially perilous part of the coaching process. If the teacher is not on board, we might as well wrap things up there.

The importance of critical evidence in this phase of the coaching session cannot be overstated. Without it, the teacher can, quite rightly, say, “Well, I don’t agree. And where do you go from there?” With some clear, objective, evidence presented sensitively, however, most teachers jump on board and are ready to embrace making a change to their practice.

Example from coaching Tom

I asked began with a situational question:

Talk me through this phase of the lesson (I showed Tom a photo of the Do Now)

Tom began to describe the choice of questions for the Do Now. I realised my question was too vague, so I asked a more focussed situational question:

Describe how you collected your students’ responses to the Do Now.

Tom’s response was to talk me through the mechanics – he used the mini-whiteboards – but then he started describing some element of the third question that was not relevant to what I wanted to talk about.

So, I changed tact and asked an awareness question:

How many students got Question 1 wrong?

Tom thought for a moment and said:

At most 3.

I was really careful about how to handle the next bit. Tom was mistaken, and I had the evidence to prove it. But this is not a gotcha moment where I reveal how smart I am and how foolish the teacher is. I said I thought it might be a bit more than that, and so I tested it by taking photos of the students’ boards on the back row.

The moment he saw the four photos, he was with me, nodding furiously.

I was tempted to dive in and tell him why I thought this had happened, but I wanted to allow Tom to provide the solution.

Straight away, he had it: There is too much data on the boards!

And then we were off!

6. We discuss actions we can take to solve the problem

The overriding goal and steps to solve this problem can come from the teacher or the coach. After presenting the critical evidence and establishing that the teacher is aware of the issue, it is always worth asking: “What do you think we can do about it?”. If they have a strong suggestion, then that is great as they are likely to buy into it more. If they are unaware, this tells you something valuable about their mental model, and determines how directive you need to be.

The solution steps must be specific and actionable. Just as you don’t want something vague like: Ask better questions, you also don’t want some mega-complex twelve-step process that will be cognitively overwhelming for the teacher to follow in the heat of a lesson. The key here is a specific step that the teacher can implement the very next lesson.

I hope the ideas in the rest of this website will be useful when choosing an appropriate action step to address the issue.

Example from coaching Tom

When shown the photos, Tom realised there was too much data on the mini-whiteboards, and wanted guidance on how to reduce this without fundamentally changing his Do Now routine.

The solution we came up with was that students would do their working on their mini-whiteboards as usual, but when it came to going through the answers they would copy their just final answer for Question 1 from one side of the board and write it nice and big on the other. This will reduce the amount of data that Tom needs to process to just one per board. Students would then repeat this for Questions 2 and 3.

7. We plan for an upcoming lesson

There is no point in improving the lesson we just discussed. That lesson has gone, and the teacher might not teach the topic for another year. It is far better to plan improvements for an upcoming lesson.

Plan the step together. Co-script precisely what the teacher will say and do. This helps with buy-in, improves the chances of success, and also reduces the stakes for the teacher due to the shared responsibility. I often say: If this doesn’t work, blame me!

Example from coaching Tom

Together we wrote a series of instructions the teacher would give his students when it was time to go through the answers to the next Do Now:

8. We rehearse

The impact of the suggested action phase lives and dies on whether you rehearse. Research suggests that allowing the teacher to approximate the action they will take in the coaching session enhances teaching performance more than if that step is just discussed.

Not rehearsing is like presenting your students with an explanation and then saying “Does that make sense?” without checking their understanding with a follow-up question. Rehearsal allows you, as a coach, to see if the teacher has understood what has been discussed. It also allows the teacher to try out the idea in a low-stakes environment with the opportunity for immediate feedback, as opposed to in the carnage of a lesson under the gaze of 30 pairs of eyes.

Once again, Josh Goodrich’s book, Responsive Coaching, has some excellent protocols to enhance the effectiveness of rehearsal:

- Specify and plan cues – select the classroom cues that should be used to trigger teacher actions during rehearsal

- Rehearse – run repeated rehearsals of this moment in the lesson

- Feedback – give feedback after each rehearsal round

- Change cue – cycle through each planned cue.

- Randomise cues – increase challenge by randomising cues

- Raise challenge – for example non-compliant behaviour or student confusion

Rehearsal can feel weird. Here are some strategies to stop that happening:

- Explain in advance that it will happen – the last thing you want is a teacher being surprised by the rehearsal element.

- Don’t apologise – I made this mistake for months. Celebrate the fact that rehearsal will be taking place.

- Explain why we will rehearse – here are some ways to help teachers see the purpose of rehearsal:

- Be positive yourself – if you make it awkward, it will be awkward

- Go first – if the teacher is hesitant or confused, offer to have the first crack

- Coach in small groups – coaching in small groups, where everyone has an opportunity to rehearse on their specific step can take the pressure off and reduce the intensity of a 1-to-1 session. Of course, this can go the other way, so use it carefully.

Example from coaching Tom

I played the role of the student. Tom rehearsed, giving the instructions we had written, and checking I was listening. The first time he forgot the third one, so decided to have the piece of paper with him to act as a cue – something he would also do in the lesson.

Then we rehearsed instructing students (ie me) to copy their final answer to the other side of their board, hover the board face down, and only show on 3, 2, 1. At first, I followed his instructions. But as he got more confident, I started not to follow them to the letter so he could rehearse how to deal with that in the classroom.

Conclusion

I am by no means an expert at observing and coaching, but this template has undoubtedly helped me to get better. It provides a clear structure that I follow, with each component having a clear purpose. I hope it will prove helpful when thinking about your observing and coaching.

Want to know more?

These people know far more about coaching than me:

- Adam Boxer – in particular, his Hypothesis model, this thread about coaching, and our podcast conversation.

- Ollie Lovell – our monthly podcast conversations regularly include coaching reflections, for example, this one and this one

- Josh Goodrich – his fantastic Responsive Coaching book, and our podcast conversation about it

- Sarah Cottinghatt – her Cognitive Coaching newsletter, in particular, this post about three lessons Sarah has learned, and this post about praise.

- Peps Mccrea has a great thread about rehearsal.

- This research paper from the StepLab team talks about effective ways to support teacher change

- I also regularly revisit Harry Fletcher-Wood’s book, Habits of Success, when thinking about supporting change that sticks

Implementation planning

Here are the ideas we have discussed:

Part 1: My lesson observation template

- High-level overview

- The technology

- Context

- Lesson commentrary

- Specific praise to prompt

- Hypothesis

- Critical evidence

- Diagnostic questions

- Suggested actions

Part 2: Format of the coaching session

- I thank the teacher for letting me watch their lesson

- I draw the teacher’s attention to the phases of the lesson that I watched

- I ask the teacher to tell me the good things they did during the time I was in the lesson, and why they did them

- I prompt praise

- Diagnosis, Hypothesis, Evidence

- We discuss actions we can take to solve the problem

- We plan for an upcoming lesson

- We rehearse

Use these to complete the prioritisation exercise here.

Book and 90-minute online workshop

***You can purchase a book in paperback or on Kindle on observing lessons and coaching, or a 90-minute online workshop on supporting teacher change that you can share with colleagues at a CPD event or departmental meeting***