You can download an mp3 of the podcast here.

Mark Roberts’ tips:

- Use Post-it notes to find out what they don’t understand (02:54)

- Use non-verbal gestures for better behaviour management (08:06)

- Don’t give negative managerial feedback (14:14)

- Stop talking about grades (23:34)

- Rephrase to amaze (34:48)

Links and resources

- On Twitter, Mark is: @mr_englishteach

- Mark’s blog is: markrobertsteach.wordpress.com

- Mark’s books are: Boys don’t try and The boy question

Subscribe to the podcast

- Subscribe on Apple Podcasts

- Subscribe on Spotify

- Subscribe on Google Podcasts

- Subscribe on Stitcher

View the videos from Mark Roberts

Podcast transcript

Craig Barton 0:00

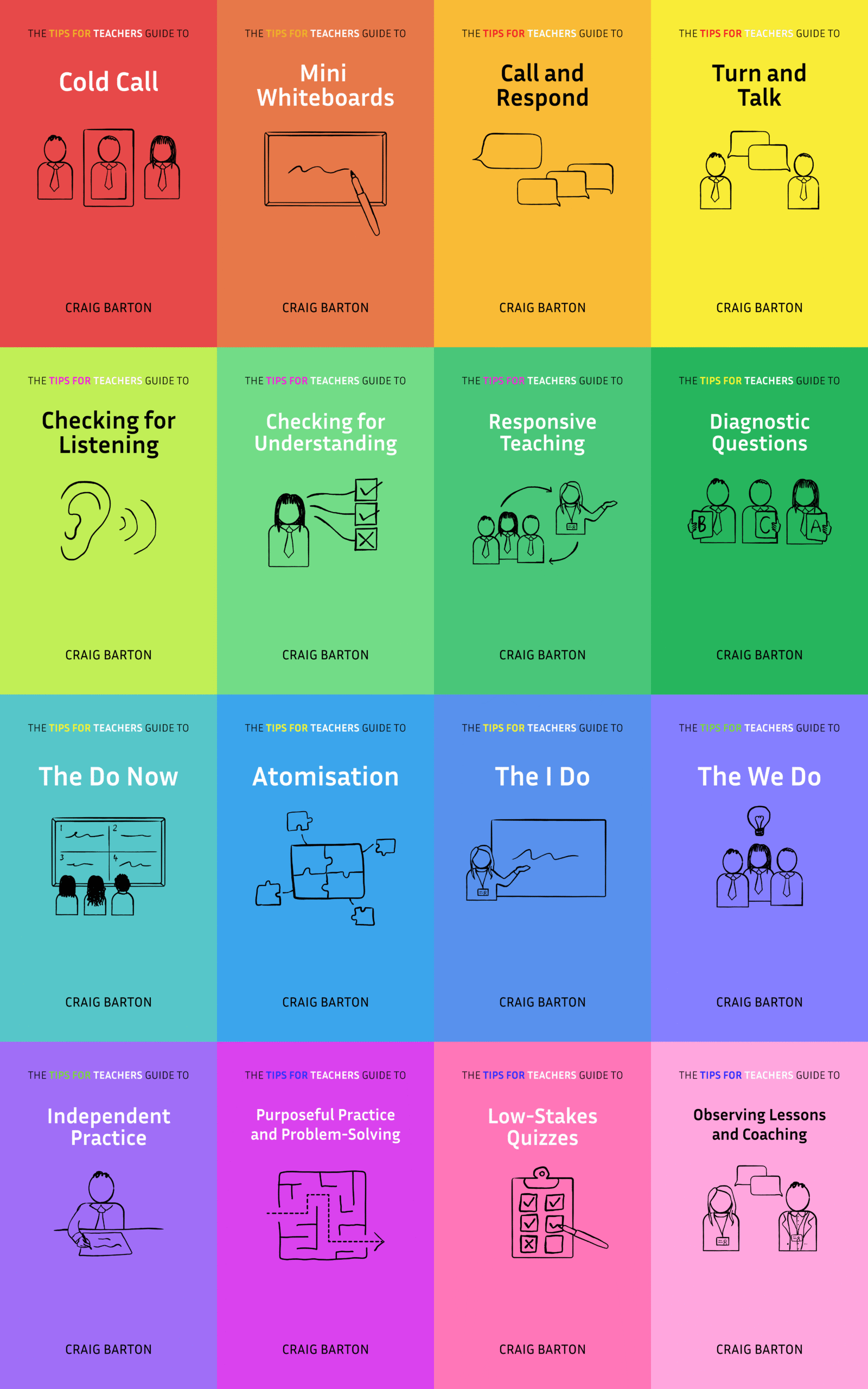

Hello, my name is Craig Barton and welcome to the tips for teachers podcast. The show that helps you supercharge your teaching one idea at a time. This episode I had the pleasure of speaking to English Teacher and Author Mark Roberts and this is a great one. Four quick things before we start. Firstly, sponsor slots for the podcast are open. So if you want to let the world’s most interesting listeners know about your book, product or event, just drop me an email. Number two, you can view videos of all marks tips on the tips for teachers website. These videos are great to share in a department meeting or training session. Number three, you can sign up to the tips for teachers newsletter, to receive a tip in your inbox most Monday mornings to travel with your classes in the coming week. And finally, and this is probably the most important one for me on a selfish level. If you find the podcast useful, please could you take a moment to review it on your podcast player of choice. It really does make a difference. Thanks so much. Okay, back to the show. Let’s get learning with today’s guest the wonderful Mark Roberts spoiler alert. Here are marks five tips. Tip one, use posting notes to find out what they don’t understand. Tip two, use non verbal gestures for better behaviour management. Number three, don’t give negative managerial feedback. Tip Four stop talking about great. Tip Five, rephrase to amaze. It’s a really good old machine. If you look at the episode description on your podcast player, or visit the episode page on tips for teachers.co. UK, you’ll see a timestamp to these tips. So you jump straight to anyone you want to listen to first of all we listen. Enjoy the show

well, it gives me great pleasure to welcome Mark Robertson the tips for teachers podcast. Hello, Mark, how are you?

Mark Roberts 1:56

I’m fine, Greg. Good evening, it was good to speak to you.

Craig Barton 1:59

Good to speak to you too. And for the benefit of listeners. Can you tell us a little bit about yourself ideally in a sentence?

Mark Roberts 2:05

Yeah. So I currently work at Carrickfergus Grammar School in Northern Ireland. I’m the country’s first director of research. And I also teach English as well.

Craig Barton 2:16

Amazing, right? I’d say well, let’s dive straight in, what’s your first tip you’ve got for us today.

Mark Roberts 2:21

So my first tip is to make sure that you use post it notes to find out what they don’t understand. Now, this is specifically a particular time in your curriculum sequence. And I use these post it notes in the lead up to assessments. And the reason I do this, I’ll explain first of all, what I used to do, and then why I do what I do and how it works in practice. But what I used to do is say to students, does anybody have any questions about this assessment that we’ve got coming up? And sure enough, you know, one or two students would put their hands up? Because I’ve since realised that asking students any questions is just about the most pointless question that you can ask. And that there’s actually research that’s been done into students their response when you ask them any questions, and they don’t answer because they’re worried that if they put their hand up and say, I don’t understand this, that they’re gonna look stupid in front of their peers. So I wanted to get around this. And it took me a little bit of time to cut them onto the fact that they did have questions, they just weren’t going to publicly admit them. And I tried different things where I’d go round and ask each table, you know, can anybody tell me one thing that worried about and that wasn’t working either. So So one dad said, Okay, I’ve had enough of this, gave them all a post it notes anonymously, I want you to write down, every single person has to write down one thing about the upcoming assessment that they’re worried about, that they don’t understand that they’d like me to come over, go over again. It can be anything at all, there’s no stupid questions, everybody’s got to do one. And then what they do they come and stick them on the board whenever they’re done. And what I do in the lesson, if I can cover them, or if not in the next one or two lessons, I go through these post it notes and I answer them one by one. But I say one by one actually, what you find is that tends to be patterns where students usually have the same kind of worries, the same kind of misconceptions, the same kind of things that I’ve not taught effectively, are not explained carefully. And I start to group them together, and we’ll start to answer them within topics. And one thing that’s particularly helpful, it gives me immediate feedback in terms of areas that I need to cover rather than just asking them generally what they think. And secondly, I think it’s really reassuring for students to know that actually, they they’re usually worried about the same kind of things and that they’re not this anomaly where they they’re stupid and they’ve struggled with something and that is something that is brought about from students saying, you know, No nothing I want to ask to having some fun from every single person in the class.

Craig Barton 5:04

While I love this, I absolutely love this right. So 211 kind of observation. And one question for you here, Mark. Yeah, so the observation is, I completely agree with you with this. Anybody got any questions? I used to ask that for years and years and years. And I’ll tell you the mistake I made, I assumed that silence was a signal of understanding. So if nobody said anything, I just assume everyone must get it. But of course, it’s, if anything, it’s the complete opposite. If if if people aren’t saying anything, and it’s either that they’re, as you say, too scared, they don’t want to be embarrassed in front of their peers, or sometimes they’ve such a lack of understanding that they can’t even formulate exactly what it is they want to ask the question about. So yeah, getting rid of as anybody got any questions, that’s been a big improvement in my teaching. So I love that. But here’s my question for you. Whenever REM I use diagnostic questions, and I say to students, okay, 321, show me your answers. And they vote ABCD. What you often get is like a tactical delay, where you’ll get some kids who just wait that extra second just to check what their mates have done. And then they’ll either swap their answer to match that, or they’ll stick with their answer if a lot of other people have gone for it. I’m just wondering, even though you anonymized the post it notes, you get that some kids just want to wait a little bit until a few post it notes are on the board is is there a way that you just ensure that even with this strategy, you’ve got that students are still kind of open and willing to share their questions, if that makes sense?

Mark Roberts 6:28

Yeah, it’s a fair point, I think that the beauty of of sticking them on the board, even students who sat really nearby can’t actually read what are on the other students post it notes. So there’s less that that sense of I’ll just put what they put. And also I get them to do it right at the start of the lesson. Usually when I’m doing my retrieval practice, and it’s very much individually in silence. And I’ll go around and just make sure that that’s not happening. So I usually get questions from from our students. And there’s usually a range even within the same topics. And some of them are really, really basic questions such as, can you tell me how long the assessment is? What what do we do if we can’t remember a quotation or things like this, whereas others will be particularly specific and technical? You keep mentioning this one particular word, can you give me a definition of it again, because I’m still struggling with it. So you get a whole range of questions. And I just find it particularly useful and I’ve not had any kind of pushback or complaints about it. It’s something that they all just just go along with now. I love it.

Craig Barton 7:32

I love it. All. Right, Mark, what is tip number two, please.

Mark Roberts 7:37

So tip number two is to use nonverbal gestures for better behaviour management.

Craig Barton 7:44

Tell me why you’ve intrigued me straightaway.

Mark Roberts 7:46

I’m gonna give you seven reasons why I think students, white students respond much better to nonverbal gestures, rather than being told explicitly. And I think that this is something that I’ve posted about before I’ve tweeted about this, and it’s gathered a real lot of attention. And for me, it’s something that I just always assumed was a bit of a no brainer, that the less that you have to talk as a teacher is a good thing. So the first thing is that it saves your voice I know is we’re coming towards the end of the year, that’s a really important thing. As a teacher, I know when I get to this stage of the year, I start to get increasingly croquet. So on a very practical level, just putting your finger to your lips, instead of having to say can you be please be quiet is saving the vocal cords. The second thing is it stops you from disrupting the flow of your explanations or if you’re reading aloud or something. So say for example, today, I was reading to my, your eighth class, notice that a couple of students were just having a tiny little off task, little giggle at each other very low key, but I could kind of give them the signal, look down your phone. And I could carry on reading at the same time. So it’s really seamless. And it stops me from having to add that kind of cognitive load of stopping the rest of the cluster to tell some one off. The other thing is that it doesn’t draw attention to those particular students. If I just said the two students names be quiet, immediately, it brings attention to them. And some students like that attention because it brings them that the kind of kudos of the social rewards of being shown that you’re messing around. So it takes away the opportunity to do that. Which also The next reason is it avoids any kind of conflict. You know, you’re always picking on me, you’re always, you know, saying I’m doing stuff wrong. And I know there’s a few students that I teach that if I said to them, you know, can you stop doing that? It would immediately get their backs up. But if I if I just kind of give them a lock or if I kind of point to say sit down or something like that, immediately, it reduces that sense of confrontation. Now, the other thing is, and I think this is massive for teachers, is it’s proactive, it’s preventative. So rather than allowing things to escalate, and getting to the stage where I’ve got to stop giving out warnings, and demerits, and so on, it enables me to do something in a way that’s nipping something in the board, without really anybody else noticing, immediately. And that the next part of that is that it really can reduce your stress levels, you can be really calm by not having to raise your voice, you might kind of raise the intensity of your stare when you give them that look, things like that. But it’s something that a lot of the research that I’ve read around teacher wellbeing shows that that proactive gestures can really cut out this sense of stress and anxiety that we feel when we get into that kind of conflict situation. And the final reason is that these signals are pretty much universally understood. So there’s not really that that issue around am I saying something in a potentially sarcastic tone, I’ve said something that comes across as a bit snappy. Instead, if I if I turn my fingers around like that to say, sit down, it’s obvious what I’m saying. And they all understand that. So yeah, seven reasons why you should use those nonverbals.

Craig Barton 11:24

I love I love anything like I love anything that like this, these little kind of micro Tips and Tips within tips. I absolutely love this right up my street, there’s so so again, same thing, kind of one observation, the flow thing isn’t something I’d considered before. But you’re absolutely right, there is nothing worse than when you’re mid flow through an explanation or a student’s given a response. And then you have to stop because somebody’s messing around. And then you’ve then got to try and reset and think where you’re at. And you know, you’ve lost a load of the kids and are so annoying. So this nonverbal, I absolutely love that. Now, the thing I was gonna say is, so I record these interviews, we put these out as an audio podcast, and we also chop them up as videos and put them in as videos. I’m always trying to push more people to the video. So this is a perfect opportunity. Give us some of the best gestures here, Mark What so this is for the benefit of the podcast listeners, you’re gonna have to watch the video on this. What are some of the big hitters? So you’ve done the the kind of turn around? I’m

Mark Roberts 12:22

sure she’s obviously well, no, you’ve also got the kind of settle down yet like you should be reading now. Ah, nice. You should be writing now. You’ve also got the kind of the finger work should not be should not be doing that. And then also you can do the kind of like referee Get a move on on of signal. Yes, yes. Come here. Those kinds of things. So yeah, so that’s the ones that they kind of come to mind. And then of course the classic the teacher stare

Craig Barton 13:06

I love it. I absolutely love those. So podcast, listeners will have to hop on the video to see the full range of those. I also love just the final point, HELOC. The fact that it almost again, I never considered this before to you’ve just mentioned that the fact that you can be more consistent with these nonverbal ones because there’s not that change in the either the tone of your voice, the pitch the volume of your voice. So you can I mean, we all were always told with behaviour, that consistency is a really important thing. You deliver these signals in the same way to every single child that so it’s not the case that sometimes you’re a bit more tired, you’re in a bad mood yourself, so you lose it a bit more. It’s always a sign that feels like it’s a really important part of this. Yeah. Fantastic. Robach, what is tip number three?

Mark Roberts 13:51

Okay, this next one is a little bit bigger. So, when you’re giving feedback, don’t give negative managerial feedback. I’m gonna have to explain that that term. It’s a term that I first came across in the work of Carolyn Morgan 2001, this study came out. And she defined negative managerial feedback is feedback that is obsessed with task completion, presentation, those kinds of study habits, rather than necessarily the work itself. And the reason I became really interested in is in it is that she found in her research that boys are far more likely to get that kind of feedback, whereas girls are far more likely to get feedback that improves them as learners. So the kind of thing that you often see with written feedback, you should have finished this. Why are all the boxes filled in? I expect more detail for this. This is to scruffy, you need to use pencil instead of pen. Those kinds of things I’ve even seen is this it question mark written on unbox and my hamsters those were clearly obviously it is it because it had demography it wasn’t, but those kinds of things. Now, I’m not saying that presentation is not important and I’m not saying that productivity is not important but when we obsess with how much boxes have been filled in rather than looking at the actual quality of the work and what they’ve done that could be improved and, and getting down to the nitty gritty of the success criteria. When we do that we’re sending out these messages that say, we we care more about whether boxes are filled in rather than you think in art. And I know that Mary Maya speaks and writes about this really eloquently as you would expect. And it’s something that I see frequently that teachers are doing. And when when teachers say, Well, you know, I want to I want to control the presentation, I don’t want it to be sloppy, and so on. And so what you can have those kinds of conversations, but don’t make that the main feature of your feedback, don’t make it the only thing that you pick out on if you’ve bothered to sit down and mark their books, or you bother to give them verbal feedback. And all you’re talking about is those kinds of things, you’re creating this really negative relationship, whilst at the same time, you’re not really helping them know what they need to do to get better. And this research shows that it leads with students who get this kind of feedback, it leads to them enjoying activities, less, they lose confidence in their own ability. And they do also start to dislike the teacher. So there’s various reasons why you shouldn’t do it. But I think it’s something that teachers often fall into the trap of doing this, you know, they’re frustrated, they’ve marked 17 books, and they keep on seeing this same kind of trend. They’re frustrated and they kind of take it out on the on the ink and and that’s something that I think we need to really reconsider. While this

Craig Barton 16:57

is a good one, you’ve you’ve got me thinking again, you Mike I love there. So so the first thing that springs to mind, I don’t think I’ve done one of these interviews yet where I haven’t referenced Dylan William, I always like when he says about feedback that it should improve the the learner, not the work, not the specific task. And this feels right up the street of of second second thing says, I’ve been guilty of all these mark, because it’s so easy to give that kind of feedback, isn’t it? Because it’s very visual, isn’t it? Like if you see a scruffy piece of work, it’s the first thing you notice is that it’s scruffy. Or if you’ve given some rule, like you’ve always got to underline whatever, it’s so easy to spot that hasn’t been done. So I’ve definitely been guilty of all that. I find it fascinating that the research suggests that it’s given to boys more than girls, it’s one of those things now doesn’t surprise me that you’ve sat at some thinking that’s exactly what I’m doing when or when I’m giving feedback to buy. So this This is terrible. So my my big question for you is, and it’s a bit of an unfair question, but I’ve got to ask it. So if you’ve got someone in your class, who is really, really their work is really scruffy, it’s really poorly presented. And the thing is, we know that their work, like there’s some good stuff in their work. But we also know that if they produce that kind of work in an exam, they’re going to do well to get a lot of the marks because the examiner is not going to take the time to read it perhaps that we would do and so on and so forth. How do we help that child improve their presentation, because my go to would be to write those kinds of things on their work. But now I realise that’s not a good idea.

Mark Roberts 18:21

So let’s say a student’s work is genuinely illegible. That is a massive issue. And we can’t leave that we have to do something about that. So I’m not necessarily talking about students, so you just can’t understand it. That’s a real problem. And that has to be tackled. But we’re talking scruffy is different to illegible. And if it’s something that it’s indicative of a kind of poor attitude towards their work and not really paying attention and so on, rather than the fact that they’ve not got particularly neat habits in my exercise books were never particularly needs, my handwriting is pretty, pretty ropey. But if it is something where you think this is an issue, what I’ll do is when I’m giving my feedback to them, and usually I do this verbally, I’m not a big fan of market. I’ll talk to them about their work, I’ll talk to them about things that I want them to improve on real areas that they can develop. And then often a bit later, usually on the way I’ll ever quit work with them. I’ll just say one other thing I want you to think about is just look at the state of your book and just show to me that you really care about it. And just smarten up a bit with your efforts. And I think that that because I’ve spent a lot of time giving them that that helpful feedback, they’re far more likely to take it on board.

Craig Barton 19:38

Absolutely. And final one just on this mark. Now, if anybody was sad enough to listen to these and do a drinking game at the same time, many whiteboards will be a good thing to have a shot to because it comes up every single conversation. I’m thinking here that I visit quite a lot of high performing schools that aren’t particularly bothered about students exercise books, and I’m talking from a maths perspective here, because they realised that the the kind of the the way to get good at maths is just to do maths. And if you spend in 10 minutes trying to set a question out really neatly versus 10 minutes answering five questions, as long as they’re legible as you say, you’re better off doing doing the latter. I just wonder whether mini whiteboards another potential benefit of them here is for those students who are a bit scruffy, one encourages them to write a little bit bigger to you don’t have that permanence that is like scruffy work in their book that’s always there. You know, it doesn’t matter. If you scruffy the mini whiteboard, hold it up, and now we can rub it off or what watch it. What’s your view on that?

Mark Roberts 20:34

Yeah, I think that makes sense. And I, I think that the question you’re asking, though, is kind of what what are our exercise books for? Yeah, if they’re there that is just there to allow you to do lots of practice. And to, you know, to write down the answers to retrieval practice and things like that, that’s fine. But I suppose that we were hopeful that they’re going to be really useful when it comes to revision as well, when it comes to them using them for study skills. And I suppose this is where the presentation side of it comes into it. And people think, Okay, well, if they take really effective neat notes, they’re far more likely to use them. I think that it is a bit of both isn’t that I think that you on the one hand, you don’t want them to obsess about everything being neat and underlined carefully and spending hours on that. But on the other hand, you would like to think that there are certain parts, at the very least, where they’re using Cornell notes, and so on, and that they’re going to be really effective. Basis is for the study. So I think a bit of both to be honest, but yeah, there’s certainly no reason why you can’t make greater use of the mini whiteboards as a way to get away from this obsession.

Craig Barton 21:41

Just just one bonus question on this mark. I’m always I love speaking to non mathematicians about this. So my theory or my view on maths exercise books is that kids never ever use them for revision, like once they’ve been used in the lesson. Forget it, because it’s so hard for two reasons. One, it’s so hard to find what you know, in your exercise, but what you want to revise, it’s often kind of scattered all over the place. But to that it’s very hard to wait. It’s quite a poor technique to revise math simply by rereading your notes or whatever you want to really be doing it. And it is quite hard to quiz yourself using an exercise. But how does it work in English, like Dickens genuinely use their exercise books and classwork to revise in an effective way.

Mark Roberts 22:24

I think certain parts that say for example, we watch a documentary that allows enables you to have context into the background of one of the novels that you’re studying. And you get them to take notes using the Cornell notes format. And that’s something that then can be put into flashcards and they can use them as part of their revision. One of the things that I strongly encourage my students to do is if if we write practice paragraphs in lessons and they do a really good practice paragraph, or maybe they write down my model paragraph or something like that, I then ask them to try to memorise chunks of that to use in the exam. So they might use bits of it that are going to go on to flashcards or that they might use them to incorporate them into new practice essays. So I think there is a little bit more of a sense that they are useful springboards for revision.

Craig Barton 23:14

Got Fantastic. Okay, Mark, tip number four, please.

Mark Roberts 23:20

Okay, it’s funny, you mentioned that deliberately. And because I’m going to mention him in this next one. And it’s about teaching in the classroom trying to stop talking about grades wherever possible. And I think there’s, there’s various reasons for this one, I will go back to the classic William Black 1998, or the black box stuff, where if you stick grades on marking, we know that they don’t focus on the actual feedback. And we know that it can lead to them avoiding Tricky, tricky work in future. And there’s all of the kind of issues around settling for the expected grades, the minimum grades, those kinds of things. And I think that’s that’s something that a lot of teachers probably understand that if we keep saying to a student, you know, if you work on this, it will, it will change it from a grade three to grade four, it might limit them to thinking only about just getting a grade four. But I think that the deeper issues with it as well. And it comes down to all of ideas around intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. And I think that the more that we talk about grades, which are really these external factors, this idea of passing grades, getting a certain grade passing exams to get something out of it, you know, you get a place onto Sixth Form to do a levels. Or you might get some kind of reward from your parents, if you do particularly well. Or you might see that it is a kind of a stepping stone to a particular career where you’re going to be well paid off, or all these kinds of things. Or it might be that you get the recognition of doing really well and you get one over your peers and so on all these kinds of external extrinsic factors, the research, particularly around boys shows that it’s not a healthy type of motivation to have. And that students who are intrinsically motivated by the fact that they study and they learn for the joy of knowing more about their topic and becoming more knowledgeable and being more skilled at a particular subject, that’s far more likely to lead to long term academic success. So I think that if we keep on going in our feedback going on about grades, and going on about Mark schemes and going on about Mark bands, and so on, we’re falling into this trap of encouraging students to have these extrinsic motivations rather than the more intrinsic if you if you would develop this, you’re going to become an even more skilled mathematician, that kind of thing.

Craig Barton 25:54

Another biggie, this one flipping, right. Okay, so a few few things on this. So the first is, yeah, I mean, I won’t name the particular school. But one, one school I worked at the policy was the all the kids as soon as they got a new exercise book at the front of the book, big on the I’m talking on the cover here. They’re big target grades. So whether it was a or six or something like that. And you’re absolutely right. The problem was for some kids, like that target grade for start was based on SAT scores, and they had a tutor for the SATs, and they were never gonna get it in a million years. So they were so far away from it, that it was no motivation whatsoever. And if you say all the kids will just settle on that, and think, Well, I’ve got that in a particular assignment. So let’s just ease off for the rest of the year. So yeah, definitely, definitely see that along. And now, when I was writing my first book, I tried to get my head around all the literature on rewards and extrinsic. And actually, it’s a flipping nightmare markets, really, I find it really confusing. So one of the things I picked up on is that whilst intrinsic motivation is obviously the dream that we’ve got to go to, sometimes you perhaps need a bit of extrinsic motivation to kind of kickstart this kind of virtuous cycle where you then put a bit more effort in, then you find out you’re doing a bit better, you enjoy the subject a bit more. So you put a bit more effort in and so on, would you bind to this degrades play a role in that in in any way? Like, if a kid’s like not doing much work? And you say, What, you’re in danger of failing here. But if you put a bit of effort in or Well, now you’ve improved it by too great. Does that play any role in the short term? Do you think at all?

Mark Roberts 27:28

No, I’m not convinced, I appreciate that the kind of dichotomy between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, it’s not that simple. And we all have certain elements of extrinsic factors that motivate us and so on, you know, obviously, we go to work because we’re paid. But we stay in jobs in the long run, because we get the satisfaction out of the job, we feel valued. So yes, there may be these these kind of little short term influences. But I’m convinced that that taking grades out of your conversation in the classroom, really reduces that not just the the intrinsic motivation for students reviews reduces the concept of extra extrinsic factors, it also takes a bit of pressure off them. And there’s not this sense of constantly having to think about the exams all the time. And when students say to me, you know, what’s my target grade or stuff like that, I’ll say what you mentioned, you know, I can go on the computer if you want, and I can have a look. And it’ll tell me, what you should be getting based on what the computer thinks you will like it 11, we can do that if you want. I don’t think that’s going to be particularly useful. But we can do that if you want. And I always say to them, if you do what I’ve asked you to do, and if you keep working on these particular areas, the greater the exams will take care of themselves. So let’s not get bogged down by worrying about that. As far as I’m concerned, we’re going to work on becoming better at English. And over time, anything can happen. And I just think that this is something that we start to limit students ourselves as well. If at the start of the year you go on and have a look at all your classes target grades, you start to think okay, well, yeah, yeah. Okay, so he’s gonna be a baby. And I want I want to do this, actually, again, I won’t name schools or anything, but I want to have a teacher at the start of the year, start of year 10. Set out all the rows of students, the grade fours are at the front, grapevines, the next, and so on. And I was like, why are you doing that? Oh, well, it enables me to get around and offer them more kind of precise differentiation. And I said, alright, well, you’ve decided what they’re gonna get right at the start of the year, in a two year course. Oh, yeah. I’ve not thought of it like that. So I just think that it influences also influences students and whilst there may be some short term boost out of it, in the long run, those kinds of performance goals, those kind of performance targets, don’t help them it makes students lose Confidence, it makes students feel as if they’re going to be found out in the long run. And it makes them more likely to avoid complex tasks. Where if we just say, Okay, let’s not worry about grades, let’s just worry about becoming better at this. And we’ll see what happens.

Craig Barton 30:14

Right. Okay, let me let me push it a little bit on this one. Now, I will say for the record, I’m almost entirely on board with you here. But let me just ask you two things. So the firstly, just on a practical level, if you mark an assignment, or maybe even a mock exam or whatever, do you put a grade on that? Or is it just a mark? And could you argue the Mark has the same impact as the grade? Or are they different?

Mark Roberts 30:37

There’s certain times when you This is unavoidable. So absolutely, when it comes to these big assessments, where my school we key stage three, we use a percentage out of 100. We bounced that up against the average score within the year group, and so on, so that they parents get an understanding the students get an understanding of where they are roughly. And when we get to do so, so us and we do mock exams, yes, we give them a percentage, and we give them a grade. And that’s unavoidable. It’s something they have to do. But I noticed as soon as I give back the papers for them to look back at the feedback, what did they do? First of all, they look at the grades and they all share, what did you get? What do you get what you get? And I want to reduce that as much as possible, I want to take that out of the equation as much as possible. So whilst I have to do that a few times a year, the rest of the time, I’m not going to play that game.

Craig Barton 31:32

Right. Okay. Last point on this one, before I hand over the final tip. What about let’s picture this scene? What about you’ve got a kids and I’ve taught a few of these, and maybe you have two, who is genuinely motivated by by grades and getting better, you know, you’ve got this kid who prompts you know, they they’re currently that they’ve done an assessment or whatever, they’re on a grade six, and they say, you know, I really want to get this grade nine. So I’m going to keep working hard, and I keep it and you You’re, you’re saying, Okay, well keep working out, but I’m not coming in to tell you where you’re at and so on. Could you think that there is an argument to be made, that grades can be intrinsically motivating or not?

Mark Roberts 32:12

So I see it in those kinds of circumstances, a student who’s aiming for the very top, you’re you’re not going to limit them in any kind of way. I would say, Okay, well, this is what you need to do to be trying to present the best possible essay, the best possible answer, the best possible story? Is this going to get a great mind? But I’m not sure. I think that if you put all these things together, it would probably get that, but it’s something that is out of your control. And you know, the old cliche about controlling the controllables, you know, worrying about am I going to get this grade nine, we know as teachers that only about two and a half percent nationally get it. And I’ve taught lots of students who’ve got it. So I’m not saying it’s not, it’s something that’s out of reach. But I suppose that I tried to reframe it and just say, Listen, you want to get a really, really good mark for this, that’s absolutely fine. I’m gonna show you how to do it, you do this? Let’s see what happens. And I just think, again, you can minimise it, whilst at the same time not dampening down their motivations. And we’re gonna,

Craig Barton 33:21

yeah, sorry, I was just gonna say, I guess the same thing would apply. You’ve got a kid who, though they really want that grade five, because it’s going to open some doors or something like that, I guess it would be the same argument, right? That, you know, it’s let’s not focus on the grade five, let’s focus on doing all the work and then hopefully, it’ll take care of itself. Would that be the message?

Mark Roberts 33:39

Yes, I’m just thinking of a student who’s just just sat is GCSEs. For me. And I know that we do modular in Northern Ireland still, so they did some exams in November. And in the lead up to the exams, he kept saying, I’ll be happy with a CMA if I can get a C in English, I’m sorted. And I’ve got a little bit cross with him only for the benefit of the rest of the group and descent, I won’t be I think you’re, you’re capable of doing really well. And I don’t want to want to see anyone settling for less and just, you know, being comfortable and coasting. And he got his modules and in one of the exams, one of the units he got an A and I said to him at a point you’re saying to him afterwards, you know, that’s why I wasn’t happy with the see for you. And he he saw that and that’s something that I think can be a really valuable lesson for them. And yeah, we ended up talking about grades in that occasion, but it was one of the reasons why we fall into this trap. Earlier on we start to limit

Craig Barton 34:35

cheese that that would have been some story could have ended up getting a d at the end of that but looking Alright, my last tip number five, please.

Mark Roberts 34:44

Okay, so tip number five is my little kind of one of my little favourite sayings. When I’m talking to teachers about the kinds of things that you can do to boost students confidence is rephrased to amaze. So rephrase to amaze is my little catchphrase for when you’re questioning students, and a student gives you a response. And this response is correct, but very basic. So it’s lacking say, in technical terminology, is lacking in detail is lacking impressive vocab, something like that. And what you do is you rephrase it, and you add in the technical terminology, you add in the extra detail, you add in a bit more impressive vocab. And guess what their answer is suddenly really impressive. It’s really impressive, because you’ve done a lot to embellish it and to to make it sound amazing. Now, that is something that I think some teachers do that already and that’s fine. But the thing that I do that I think is something that other teachers might find particularly useful, is you don’t just leave it there. You come back to this, this answer at some point, either in the lesson or preferably in future lessons, where you say, you remember the other day when we had that amazing answer about how volcanoes erupt. And you remember how we looked at the concept of bursts and we use this particular word and so and the student who’s given this answer is motivated because they’ve given this this amazing answer. And the other students start to look to to them as this kind of resident volcanologists, this resident expert within within the classroom, and it’s a little bit of a it’s a bit of a cheat. It’s something that you orchestrating get a little bit and it might not be for the teaching purists. But I found that this is a really good way to switch on demotivated students, and I’d never do it have an incorrect answer. If it’s incorrect, I’m gonna say no, because that would be that would be wrong. And that wouldn’t be helpful. But if it’s correct, but but basic answer, yeah, go to town with it and make it sound brilliant.

Craig Barton 36:55

All right, this, this is interesting. So let me see if I’ve got my head around this. So is this is it the case that student gives a correct but basic answer, and do you say then rephrase to amazing, then they do the work? Or do you support them with a rephrase it? How does it work?

Mark Roberts 37:11

I just rephrase that. So so say I say to a student, okay. Why do we think that Dr. Jekyll is creative, Mr. Hyde? And they come back with a basic answer? Well, he wants to be able to get away with with doing things he wouldn’t be able to get away with otherwise? And I say, yeah, absolutely. So what we’re looking at, what you’re telling me is this idea of duality. And the idea that Dr. Jekyll has been able to have this kind of facade of the respectable gentleman, but secretly is indulging in all these secret vices. And then later on a couple of lessons later, you remember having the conversation the other day where Steven gave us this answer about duality and the repressed Victorian gentleman. Let’s think about that again now and stuff like that. So that’s, that’s how I tend to do it. Or this,

Craig Barton 38:03

I’ll tell you what we could be ending on a controversial note here, Mr. Because this, that we need a bit of conflict here, this might not 100%, I agree with this, I’ll make my case. And then you can come back at me here. And so I can completely see it from a motivational point of view, I can completely see how for some kids, and probably most kids, that’d be a really powerful experience. And I’ve never thought to do the coming back, you know, the next lesson that feels like something really powerful. My fear is that the child will think they’ve understood that concept to the level that they need to because you’ve kind of reframed it. And I think like Doug Lemov, would call this rounding up, where they’ve given an answer and but you’ve then kind of added the the key ingredients that make it a real sophisticated answer, my fear would be that that child thinks are brilliant, I understand that amazing. So I can almost kind of stop thinking about that now. Whereas if you kind of say, Alright, great answer, but you’re not quite there, you need to can you think what else you need to add? Maybe then that kind of extra effort goes in to get all that what would you say to that,

Mark Roberts 39:04

you’d need to check for understanding to make sure that this is something it’s not just you kind of pontificating and, and showing off and not actually going through. So I would then be be looking at examples of work, modelling, using these kinds of ideas, checking that students are using this kind of language, making that a real focus of some of the work and going back and just checking this embedded, because yeah, there’s no point having these fancy debates, discussions, throwing words around like confetti unless they’re actually being used in exercise books, and you’re seeing real evidence of it. So I might say, Okay, well, let’s go back to this idea. I think that we’re still not quite grasping actually what this concept is about, you know, Steven gave us this really good example of it, but let’s just have a look at it in a bit more detail and really break down exactly what’s going on there. And I think that that you would have to do You can’t just expect that because you’ve said something fancy, they’re automatically just going to take it in. But it’s the first step in getting them feeling successful about themselves within English, which is going to motivate them to want to do more of it.

Craig Barton 40:14

That’s really interesting is one of the things I’m going to need to think about harder about this, because it’s, it’s kind of what is the trade off? Isn’t it you the motivation, such a powerful thing? And I can imagine for some kids, that’s exactly what they need. But then I can also possibly see the flip side where they, they kind of the message they take from that is, well, I’ve actually given that answer. So I’ve what’s actually what the teacher said, that’s kind of what I said. So you know, I’ve got that understanding, I just need to think that through my final thing on this, though, Mark, this is something I’ve been thinking about myself at the moment, and I just be interested to get your take on this. I don’t want when I first started my career, I was really lazy in the sense that I would knit. So I’m talking maths here, I would set the kids a load of questions. But I would never work out all the answers myself before the lesson. Because I’d think I’m a decent mathematician, I’ll just wing it and the lesson they’ll be fine. And that was terrible. Because I lost a load of time in lessons and sometimes a really bad question. It snuck in there and not the kids confidence and so on. When I got a bit better, I always would work out all the kind of written problems, and I’ll give the kids and that was fine. But one thing I never did. And I’ve only started doing this recently, and it seems to tie in to what you’re saying there is, if I was asking kind of a question where the kids were gonna give a verbal response, I would never think to kind of script out like an ideal answer, like the answer that I I really want them to do. Because again, I’d think well, I’ll just make it up on the spot. But what I’m what I’ve started to realise now is that if I don’t kind of map that out, I can forget it. Like I get so lost in trying to listen to what the child saying there’s a million other things going on in the lesson that actually, when I then do what you’re doing there rephrase to amaze or whatever it may be. I I never get it as good as I should have done because I’ve written it down. So would you be kind of writing these things down? Would that be something that will be something that you kind of advocate for these questions, just so you can guarantee that you’re going to get that explanation the way you intended? If that makes sense?

Mark Roberts 42:08

I tend not to do in this situation, it tends to be a little bit more ad libbed, really, depending on what it is that they say. But I think that when you’re talking about things like modelling really effective answers, I suppose in maths, you’d be looking at work at work two examples a bit more, I will often think very carefully. And sometimes I will write out one in advance. And then other times, I will just do one off the top of my head because I want them to see me edit and struggle and make mistakes and give them the insight into how my mind works as a writer. So I think there’s pros and cons with these. And I think you have to think about the stage that the classes are to begin with, I want them to have like a perfectly polished answer that sort of level that they can immediately find useful as a model. When once we get a bit more beyond that I want them to see me struggle and think on my feet a little bit more, particularly if I’m doing something like an exam question against the clock. But when it comes to the kind of rephrase to emotions, now, I tend to just come up with these off the top of my head, and some of them will probably be better than others. And if some of them aren’t great, I might forget about them. If some of them are particularly impressive, I might get them to write down something on the board. I often say Oh, I like that. Let’s all write that one down. You know, wasn’t that a good thing that I just came up by now. But we’re students I’d kind of I like that idea. We’re gonna write that one down and make it seem as if the students done it as well. So these things can be captured another way I suppose.

Craig Barton 43:43

Fantastic. Well, I’ll say what might they were five obviously really brilliant tips off loads to think of there so let me just turn it back to you. What should our listeners check out what what should they need to be looking at that you’ve you’ve been working on?

Mark Roberts 43:54

So if you’re more interested in reading my work around boys my most recent book that came out in June last year is the boy question how to teach boys to succeed in school that’s available via the Routledge website on Amazon if you prefer before that Ico Alfred boys don’t try which came out in 2019 Loads of people have got that already. And then if you are more interested about my writing as an English teacher, I released a couple of years ago worst timing ever because it was slap bang in the middle of no exams a guide to how to revise in English which is called you can’t revise for GCSE English? Yes, you can. And Mark Roberts shows you how snappy title. And then I did a follow up version of that which was the a level literature version of them. And despite the timing fiasco with the exams there, it has actually been very successful because lots of students are buying it now. But also lots of English teachers have bought it because it’s really helped them with little tips and techniques, the kinds of things Now that I’ve been mentioned in today, so those are things that you might want to check out. And of course, feel free to follow me on Twitter at Mr. Underscore, English teach.

Craig Barton 45:11

Fantastic Well, I’m gonna put links to all the all the work and your Twitter on the show notes page so listeners can check that out. Final thing I’ll say just before we wrap things up. I remember it was a research head national and it was I don’t know how many years ago this must have been. I’m assuming it’s pre COVID. But my sense of time has gone completely. And you and Matt would do Mani boys don’t try sessions and I don’t know what Tom Bennett was thinking but he put you on in some like little classroom or something. And I arrived I must be 15 minutes early. So I was desperate apps. I got the book and I was desperate to your loads of questions for you. And they were queuing outside it was absolutely absolutely pandemonium so I just got I couldn’t get into watch it. So that’s why I’ve been desperate to get you on the show. To to get some of those insights are some of those questions? So Mark Roberts, this has been absolutely brilliant. Thanks so much.

Mark Roberts 45:58

Thanks very much, Greg.

Transcribed by https://otter.ai