You can download an mp3 of the podcast here.

Emma Turner’s tips:

- Use talk cubes to encourage students to contribute (02:48)

- Encourage students to say “stop!” if they are confused during an explanation (08:45)

- Ask students “What was the most useful thing I did today?” (16:11)

- Plan for error (20:22)

- Keep spare mini-whiteboard pen lids (26:55)

Links and resources

- On Twitter, Emma is: @Emma_Turner75

- Emma’s books are: Let’s talk about flex, Be more toddler, and Simplicitus

Subscribe to the podcast

- Subscribe on Apple Podcasts

- Subscribe on Spotify

- Subscribe on Google Podcasts

- Subscribe on Stitcher

Watch the videos from Emma Turner:

Podcast transcript:

Craig Barton 0:00

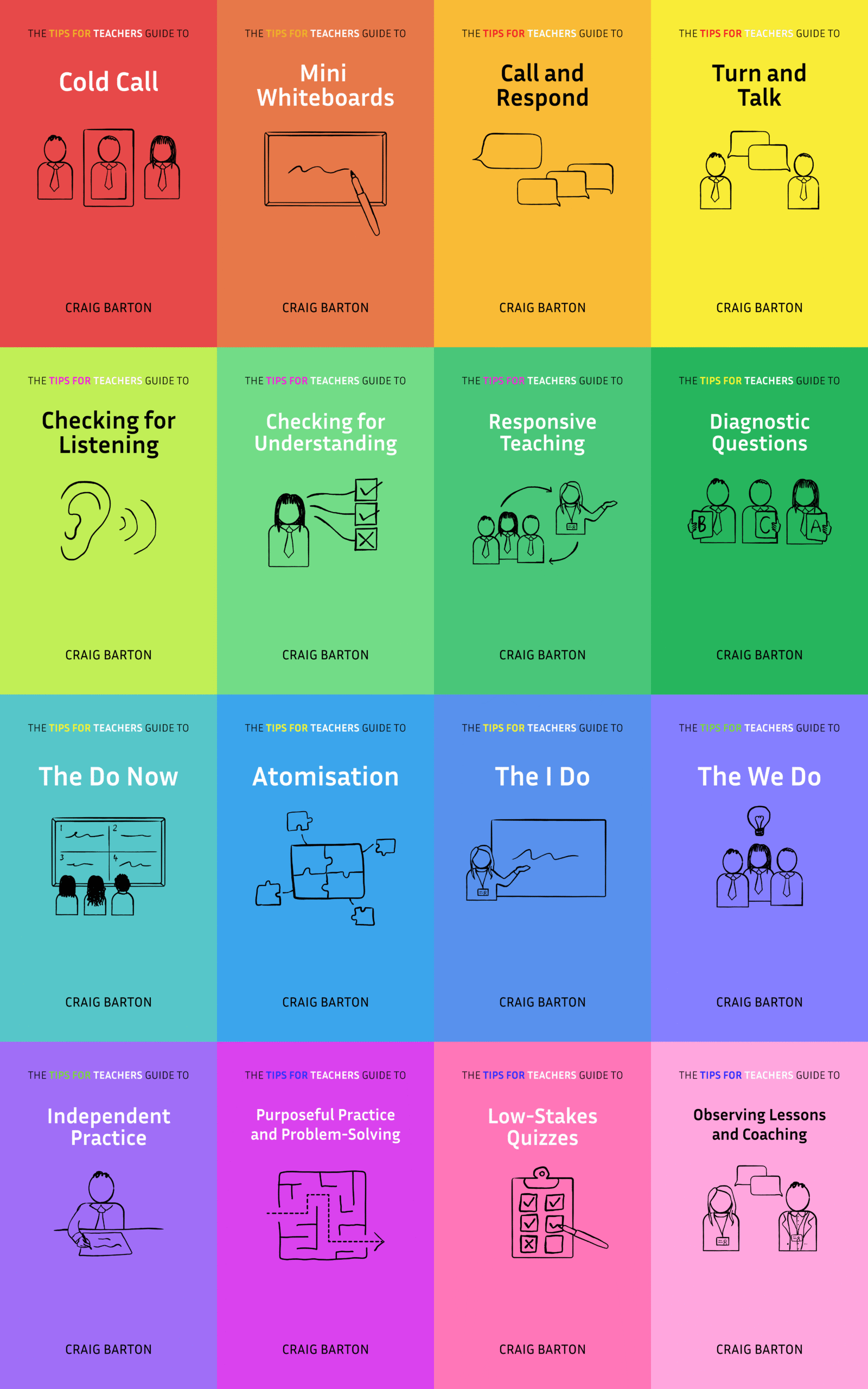

Hello, my name is Craig Barton and welcome to the tips for teachers podcast. The show that helps you supercharge your teaching one idea at a time. This episode I have the absolute pleasure of speaking to primary teacher PD lead and author, Emma Turner, and it is brilliant. Sponsor slots for the podcast are now open. So if you want to let the world’s most interesting and lovely listeners know about your book, product or event, just drop me an email. Two other quick things to remind you before we get cracking. As ever, you can view the video of all Emma’s tips plus the tips of my other guests plus all my video tips on the tips for teachers website. These are great to share in a department meeting or training session. Secondly, you can sign up to the tips for teachers newsletter to receive a tip in your inbox most Mondays and I’ve been pretty lapse with this over the last few weeks to try it with your classes in the coming week. And please tell your colleagues about this if they think you’ll be useful. Oh well extra bonus. I’m running quite a few tips for teacher CPD events in schools for the next academic year. So if you’re interested in organising one of those, I can work with maths teams or I can work across space and across subject. Just drop me an email all the contact details are in the show notes. Finally, if you find this podcast useful, please take a moment to review it on your podcast player. It really does make a difference. Right back to the show. Let’s get learning with today’s guests. And materna spoiler alert here aren’t in this five tips. Tip one. Use top cubes to encourage students to contribute tip to encourage students to say stop if they’re confused during an explanation. Tip three, ask students what was the most useful thing I did today? Tip Four, plan for error and Tip five spare mini whiteboard templates. Now, if you look at the episode description on your podcast player or visit the episode page on tips for teachers dot code at UK, you’ll see our timestamps each of the tips so you can go jump jump straight to anyone you want to listen to first or you listen, enjoy the show

well, it gives me great pleasure to welcome Emmett turn it to the tips for teachers podcast. Hello, Emma, how are you?

Emma Turner 2:23

Hello, Craig. Really? Well, thank you hope you’re alright. Very

Craig Barton 2:26

good. Thank you. Very good, right? And for the benefit of listeners, please, could you tell us a little bit about yourself ideally in a sentence.

Emma Turner 2:33

Okay, so I’ve been a primary school teacher for 24 years specialising in early math. I’m currently working as a research and CPD lead for a trust based in Leicestershire, and I write a few bits and bobs about education and curriculum. Fantastic,

Craig Barton 2:47

brilliant stuff. Well, let’s dive straight in. What is your first tip you’ve got for us today?

Emma Turner 2:53

Okay, so the first tip I’ve got for you is one that I share with all my kind of anchor youth, we’re not in cuties anymore. Are they? eects, in my cohorts that I have, and it’s about how do you get children who don’t want to talk in class at all? And how do you get those who are not keen to talk to stop talking myself and kind of dominate the conversation. So this is from primary. And very often in primary, you’ll have lots of children who are quite reticent don’t want to have a lot of confidence to speak about something. And then you’ll also always get one or two who love the sound of their own voice. And we’re quite happy to talk to Brett. So one of the ways around that that shows my ucts is to talk about talk cubes. So at the beginning of the lesson, you give everybody in the class A cube or a counter or something, and they have to get rid of it during the lesson. And the way that they get rid of it is by contributing to the lesson. And the reason I say it’s for those children who are a little bit reticent, and for those who are, you know really want to dominate is because if you’ve got a child who’s got an awful lot to say, you don’t want to clip their wings and sort of say that their contributions are bad. But sometimes I’ll give them three or five cubed and then say, right, when they’re gone, they’re done. So you have to think you have to think really carefully about the contributions you want to make. So is this a point that’s really important to you? Or is it just another chance for you to say something, so it’s kind of teaching them to recognise that everybody in the class would like to contribute at some point and to think carefully about the ones. So they either have three or five, and once they’re done, they’re done. Or everybody has at least one, so they have to contribute something. So there’s a lot of talk about cold calling, and you know, kind of asking any child at any point, but for some children, especially young children, that is again quite overwhelming. So just saying you just have to say one thing and think really carefully about when you’re going to say it is that really really works. It just helps if you’re trying to kind of roll out a more discussion based model of teaching kind of dialogic teaching, it’s just to help manage that so that’s one that’s my first tip about getting children to talk or not to talk too much

Craig Barton 4:52

i love it i really like this right let’s dig into this a little bit more. So first thing say with with these cubes I like you could Peyton this I like this this one to go big, does the kids get the same number of cubes? Or do you differentiate in terms of like the louder ones get more cubes? How do you do that?

Emma Turner 5:08

Everybody gets at least one. So everybody has to say something. Now, obviously, that’s the extreme sensitivity, because there are some children who just for whatever if their special needs, that’s just not appropriate. So it’s not a kind of a complete catch all for everybody. But for most of the class, everybody gets one. And then on occasions, if you’re trying to sit, if you’re trying to encourage children to talk with my mic, give them two or three. And then for other children who are really, really keen to share their ideas all the time, I’ve got one particular child in my head who always wanted to contribute. You’d give them a slightly more and say, when you’re done, you’re done. That’s it, you’re gonna listen to the contributions of others think about what they might be saying, and then you don’t completely exclude them. Because what you might do is then come back to them and say, What did you think to Sammys contribution that they made, just so you can bring them back into the discussion? But you’re they’re not necessarily dominating it like you potentially can have in a classroom? Got

Craig Barton 5:59

it lovely. And I think you’ve kind of half answered or maybe even fully, fully answered my follow up question there. Because one of my things with cold call, I’m a big cold call firm. But there’s always a danger. I think that once you’ve asked one child a question, and they’ve given an answer, there’s always a tendency for them to think that’s me, I can have a bit of a sit off. Now for the rest of the lesson. Particularly it’s 30 kids in the class, what are the chances of him coming back to me, I can just imagine with these cubes, if I was a bit of a nervous child, I’d be thinking, right? Let me get my contribution in pronto, give away my cube, and then that is me done and dusted. But I’m guessing is it the fact that there’s always the possibility you could come back to a child is that what kind of keeps them cognitively engaged, if that makes sense?

Emma Turner 6:39

But you’d sort of say, you know, what, do you think Tommy’s answer? Or do you think Sammys answer? Do you agree with them, you know, so it’s not necessarily that they are leading the discussion, but you would always draw them back in it’s not a once I’ve, once I’ve dropped my kind of cube at the end of the table, I’m done, I can just sit back and think about my birthday party or play town. I’m gonna be thinking about No, but it’s, it’s more to ensure that that everybody contributes at some point that you’re not got those kind of key characters always dominated the discussion. And that you kind of send that message that everybody has something to say, and we always have, we should always value what everybody else thinks and draw them into the discussion.

Craig Barton 7:17

Got it. Lovely. One final point on this, am I really, really like this. And it builds on something I’ve been discussing with Jamie, Tom. And also Chris, such, you’ve been the previous two guests. On the show. We’ve been talking lots about mass participation. And we’ve been talking about cold call, and particularly with Jamie talking about introverted students and so on. I’m just interested in the kind of messaging you would be giving to kids who perhaps are reluctant to contribute and you’ve given them this cube? How are you? What what kind of things are you saying to say, Come on, you know, share your answer, we evaluate what’s some of the messaging that works with these kids who are perhaps reluctant to contribute naturally.

Emma Turner 7:55

I say it’s different in primary because you get to build up that relationship with the church, because you’re with them all day. So you can do little things like you’re walking in after playtime, and you just put the cube in their hand and go, I know, you’ve got something brilliant to say, I can’t wait for you to hear this is your secret ticket to tell me I’m gonna be so happy when you get rid of. So it’s kind of just encouraging them that way. But then the kind of classroom culture that you build as well, the wider classroom culture is that everybody has something to say, and everybody’s got the chance to kind of to shut to shine. But you would do it as you do in private practice in multiple different ways. You don’t leave it to the moment that you’re going to ask the question, it’s that kind of wider, broader culture that you build up in the classroom that needs to sit with any kind of walking cold on a Monday morning, go right cubes day. It has to be so part of what you do.

Craig Barton 8:43

Fantastic. Okay, well, what’s the second tip you’ve got for us today, please

Emma Turner 8:49

write this kind of fits in a little bit with the talk cubes. And this, it’s this idea of stop. Now, when I was in my last school where I was the head, and I was a class teacher there. And then were the kind of Deputy Head assistant head teacher, we had this thing called stop. And we used it right from foundation all the way to year six. And it was this expectation across the school that the children would be responsible for their own learning. So if at any point during the teaching, they didn’t understand what we were on about, it was their responsibility to stop us and and ask us what we meant. So obviously, you caveat it with sometimes you’d be introducing the lesson. And you go right, don’t say stop just yet. I know you don’t. Because I haven’t told you what we’re doing. But you would you would create this culture in your classroom whereby the onus was on them, understanding what you were saying. And it’s amazing how many children would say stop and it to get another novelty factor of everybody that started that. They had to say, where they got lost. So they’d say, Stop, I was I understood it up to where you put that Seven, I don’t know where the eight comes from. And so they would have to articulate where they got a bit lost. And it was so powerful. And it worked right the way through from foundation up to year six, and it got, it got round that bit, where you send all the children off to do their independent work. And as for children go, I don’t get it. Why don’t you tell you don’t get it. And also, it helped for those children who potentially were a bit more introverted, because those confident children would say, I don’t know where you got that six from, and then all of a sudden, you’d see lots of little eyes light up, and you think they didn’t know either, you know, they didn’t know where the six came from. So you would explain it again. And then once that culture of it’s okay to be wrong, or it’s okay not to know it’s okay to stop the teacher. It was great. And it also made you aware of where children’s gaps in their understanding where misconceptions were coming from where they’re kind of, we’re just getting an incomplete Ravel you feel I won, I know what you think that or why you don’t think that and it made your teaching stronger as well. Occasionally, there would be a group of children who you thinking, I know, you’re not going to get this at all. So you would speak to them at the beginning and say, Don’t worry, I’m going to be working with you in a few minutes, we’re just going to set this lot off, and then I’m going to call them work, don’t panic, if you don’t know, don’t need to stop me, we’re gonna come and do some special work just as just as in our little gang. But it was just such a powerful model for the whole school and they loved it. And the children loved that they were in charge of their own learning, it was incredibly effective model.

Craig Barton 11:31

That’s really nice. I love I love this. So the first thing I wrote down immediately was, you could imagine the kids saying, Stop, stop, stop straightaway. But as you say, it’s almost like I’m picturing all this kind of a bit of a stop amnesty where you can’t say it for a certain amount of time until it kicks in that that feels like it’s an important part of part of that. I like that. And then the other thing is, and again, you’ve answered this as well, the fact that it’s not just you can imagine some some characters I’ve spoke I taught in the past, just wanted to stop me mid flow anyway. So just start with the fact that they’ve then got to articulate exactly where in the point they’ve kind of got confused, that feels like it’s, it’s kind of guaranteeing that extra buy in. So they take it a bit seriously, but also helping them communicate that feels like it’s a really important part of this as well.

Emma Turner 12:14

Yeah. And the other thing was you you draw in from the other children, you say, Okay, so, you know, Rita says she’s stuck, or she doesn’t understand where the six eight came from? Can anybody else explain where this has come from? So you’d kind of bounce it back to the class as well. So you’re drawing in all of the rest of class, you’re not just having this kind of tennis conversation with one child, then you’re actually pulling in the thinking of other people. And what happened, especially in my year, sixth class, was somebody say, Stop, I don’t know where they came from. And before I could even open my mouth, somebody else would have jumped in and go, I know exactly. I know why you’re thinking that I thought that, but then I realised it was from over this side off, you know, it was that side of the triangle, whatever it was, and they would, they would sort of bounce it around the room themselves a little bit with me kind of intervening when I needed to. So it was still kind of direct teaching. But they were listening very much more to the contributions of others and reflecting on where they were in their learning, and supporting the rest of the class with their contributions as well.

Craig Barton 13:11

That is incredible. So my final question on this, I mean, I’ve always stated you could not pay me to teach primary particularly younger years, I will be so out my death is not even funny. The fact that you’re saying that this I was already in here, here, when you say you this can be from kind of foundation age, right up to kind of as year six, any difference in how this would work with like, you know, four or five year olds versus 1011 year olds? Or is it pretty much the same?

Emma Turner 13:34

It was pretty much the same, you find a young child who doesn’t want to tell you what they do and don’t know. You know, they’re they’re really, really articulate, they will say, I don’t understand why why why it’s that’s just a natural predisposition for young children is to want to know why and to want to, and they’ll tell you, I don’t get it, I don’t understand it. With the younger children, obviously, there’s a little bit more caveats thing of, okay, we’re going to listen for a couple of minutes. And then I’m going to ask you, if you don’t understand it, this is where we’d say stop, can we go over it again. So there was a gradual buildup of it. But it was completely embedded across the whole school and it as it builds on their children’s natural dispositions to want to ask why or to tell you that they don’t know things. And if you build that has to be part of a wider culture. But if you build that culture in your school, it’s hugely powerful. And a bit discombobulating as a teacher when you first start to do it, I mean, what do you mean? Do you understand it, I have a gift to teach you. This explanation can’t be anything more perfect as an agent crafting only then get it. So there is kind of a little bit of a little bit of realisation that maybe your explanation wasn’t so great, or maybe you haven’t pitched it appropriately. So it’s a bit of a wake up call as a teacher, it can be a bit wrong footing, but usually developmental as a teacher to think actually, I didn’t break that down enough. I didn’t do it in small enough steps. I had assumed wrongly, a particular level of prior knowledge. So yeah, I I really like to talk about it with all of my code.

Craig Barton 15:02

I think it’s lovely. One more bonus question a lot. That’s just prompted by and this is always the advantage of speaking to primary colleagues, the fact that obviously, you teach a range of subjects, did this work better or worse in maths versus anything else? And was there any subjects where the stops tended to becoming more frequent than other subjects? Was there any variation at all across subjects?

Emma Turner 15:21

Not really, it was the more of the type of stops that you do. So in maths, it was fair, most of the time fairly procedural? I don’t know why the eight goes there. I don’t know where you got the 11. From? were things that are a or history, it was kind of I don’t understand why. So why did they think like that? Or what? No, I don’t, they didn’t necessarily understand the wider context things or they didn’t understand people’s motivation or, or how things were different. It was, it was still that they were stopping you because they wanted to know more or understand more about to do more. But it was dependent. It was kind of subject dependent in terms of the types of questions they were asking, rather than the frequency of them stopping you much easier in mathema, se to provide the answer.

Craig Barton 16:07

That’s what I like to vantastic about well, what is tip number three, please?

Emma Turner 16:15

Again, it’s sort of linked to what we’ve just been talking about is that at the end of every lesson, I always ask my classes, what’s the most useful thing I did today? is actually what was the most use went? When did the penny drop for you? Was it when I showed you a diagram? Was it when I got you to have talked with the partner about it was when I got you to make notes? Was it when I explained it again, or linked it to an analogy, or whatever it was? What was the most useful thing I did? And then I also get them to give me a piece of feedback about what was something that was new to them today. And what was something that they were just going over that they kind of already knew, but it was practice so that I could gauge. You can’t really gauge fluency in a lesson. But it was like, what was that kind of a moment being things and what was the bit where we were just kind of going over it. But asking them what’s the most useful thing I did today? places a different emphasis on your teaching, not in I teach like this, therefore, you will follow it. And what I found was that year on year, different classes were given me different feedback, as in some classes just seem to prefer a particular way of delivery. And then others prefer something completely different, just depending on their prior experience, their proficiency with language, their current attainment, it was there was all sorts of difference. But if I hadn’t had that conversation with them, I wouldn’t have known. And it also made them much more likely to talk to me about their areas or misconceptions. If I was saying that I am constantly learning how to do this and get better. So and the only way I can do that is by getting feedback from you.

Craig Barton 17:49

And that can be you’re dropping some gold there. That is another absolute. I like this. And I like the fact there’s all this theme of kind of teachers, teachers getting better improving from the kind of Pupil voice I really, really liked this couple of questions on this one, just the practicalities, how were you collecting these responses? particularly focusing on that? What What was the thing that you felt the most valuable throughout the lesson? Is it really whiteboards what works Beseler?

Emma Turner 18:14

I had a slide that I would just pull up at the end of every single lesson. And we had some nice stuff on there as well, like, who did you help today as well, but it was like a little kind of review of our learning for that session. But I would literally just say what was the most helpful thing I did? And I would have I’d talk about the lesson and say, you know, was it when I explained that using this diagram was it when you had a chance to talk to a partner. So I would kind of narrate what we’ve done very briefly and like the shape of the lesson, and they would just put their hand up or use a whiteboard, or sometimes I would put I put four corners of the board or the things I did and they just literally had to point to which corner of the board was was the bit that was been most useful. Really quick wasn’t labelled at all. But it just gave me that snapshot of what works with this class with this subject with this topic within the subject with this particular objective. What’s the most efficient way of getting that information over to the pupils?

Craig Barton 19:09

Absolutely fascinating. So I’m going to put you on the spot now. Just feel free to tell me that you don’t remember nothing springs to mind. But does anything spring to mind of a change you made as a result of this any surprising thing that came back from one of the times that you use this for the class

Emma Turner 19:23

shutting up. So one of the things was I would explain these things in maths and I thought they were beautifully scaffolded and lovely instruction. And it was I just needed to stop more and give them a chance to process that step. And to practice that bit and then come back to it because I was talking for too long. So they were sort of saying that. When you explain the first bit we’d like to practice the first bit when you explain the second bit. So I was explaining a whole process all the way through for sort of 1015 minutes and they were telling me we like it in little kind of smaller chunks, which was, you know, great feedback for me, because that’s what worked with them. And so I did and chop it up a little bit more. But as teachers, we like to do the full narrative don’t really like to go. Let me talk you through this children sit, sit back, and let me wow, you know, shut up, shut up and doing little bits, please.

Craig Barton 20:20

He’s fantastic writer, the what said Tip number four please.

Emma Turner 20:26

This again kind of links, it’s about misconceptions driven planning. So I talked to my ICTs about this. And I say, whenever you’re planning a lesson, don’t start with what you’re going to teach start with what they’re going to get wrong. So make a list of everything they could possibly get wrong about this every single possible misconception they could have. And then plan your lesson around that. So you kind of know you’re gonna go from A to B. But as you’re getting that kind of AFL information back whilst you’re teaching, you’re and you’re finding out, Oh, they’ve got this misconception, you don’t go? What do I do now, because you’ve already thought about it, and you’ve got a screen or two up your sleeve. And if you because you’ve prepared that in your planning, so every time anybody saw me teach, they knew I’d have like 40 or 50 slides for a topic in a lesson I might own, you know, I might only use four or five. But as I was going through, I began, right, we don’t need that one. That was it because I prepared loads of screens around a misconception, but then I just skipped through them if I didn’t need them, but I knew that one year or one class, I would need them. So it’s never time wasted. But listing the things children are gonna get wrong before you start and having something up your sleeve is so much more effective because nobody walks into a classroom, and all the children follow your thread perfectly. So why don’t we plan for that? We planned them the things that are gonna get wrong, rather than overlaying the duvet of learning and saying, like, I’m just gonna tuck you all in neatly underneath all of this, and we’re all going to sit beautifully and comfortably. Let’s actually say, Okay, right, what’s gonna, what’s gonna go horribly wrong? Let’s get that right.

Craig Barton 21:54

I love it. I love it. I will do very of learning as well. That’s, that’s great. That’s very good. Very, very good. All right, so a couple of things on this one. So I’m a big, big fan of this as well. One thing I’m particularly interested here is that I think, the less experience you have as a teacher, the more difficult you’ve you find it to predict the kinds of ways kids may go wrong, maybe this is a secondary math thing. But often, if you’re a secondary maths teacher, you tend to have been pretty good at maths as a student. So maybe you’ve not made the kind of mistakes that kids are likely to mate with maths. So do you find that less experienced teachers find this quite difficult to predict the errors? And are there any strategies that you can kind of you share with less experienced teachers to help them better identify these errors? If that makes sense?

Emma Turner 22:39

Okay, so whenever they’re teaching a particular aspects, something, say, an aspect of math, I just get them to write the problem in the middle of what the problem they’re going to be teaching on the aspects. And then I get them to a spider gramme, all the things you need to know, before you can do this. So is it place value to 1000? Is it understanding the the, the sign for each of the operations? Is it being able to do an approximate kind of an estimate answer in your head? Is it? Is it understanding what multiplication or division is? So all of these things? First of all, people don’t do that. They don’t look at an objective and think, what are the prerequisites for this? We’re just saying, Oh, just got out of the elevator on this floor. This is where we go, they don’t think about all the other stages at the elevators that to get to. So there’s that one? Yes, it comes with experience as well, because you’re never quite always astounded at how much in a tangle children can get themselves. Well, have you got that frog? Yes, it’s a constant surprise. But forewarned is forearmed. And also talking to if you’ve got parallel class teachers, or if you’re talking to the youth group before, as well, especially in the primaries, if you’ve got a year three classes, talking to the year three to year two teacher and saying, what did they find really hard last year? You know, what top what were the topics or areas that they really struggled with, again, can give you a heads a heads up, that they got in a massive mess with something. But I don’t I cannot believe that people think that starting with an objective or an overview or whatever you want to call it, and thinking I’m just gonna go from A to B, and I’m not even going to think about going wrong. It’s a bit like driving with the sat nav and saying, I’m not gonna have to make any details whatsoever, there is not going to be a jam on the 50 they’re not going to be able roadworks and therefore since I’m just gonna go this way, it doesn’t work like that. So misconceptions driven planning for colleagues is so important, but a it comes with experience, but be it comes with thought as well. And you do have to put the thought into what’s come before and what might go wrong.

Craig Barton 24:42

That’s lovely. That just one follow up question. One extra follow up question on this piece. I’m fascinated by how you describe your kind of PowerPoint that’s maybe got 40 or 50 slides and some of them you don’t. I’m a big, big fan of this. So when I’m interested in what is on the slides, so if you put detects a student may make a potential error. Is it kind of more practice questions? Is it more examples? Is it a different way of explaining it a visual? What are the kinds of things that would be in these slides that you may or may not use, if that makes sense.

Emma Turner 25:13

Sometimes it’s a link to prior learning. So sometimes it may be visuals or pictures of manipulatives that we’ve used in a topic that links to it. So say we’re doing percentages, there might be loads of imagery links to when we taught decimals. And when we taught fractions. So when we tried to relate fractions, we would use the same imagery of Satan at their fingertips. So I can kind of scroll back through the imagery there. There’s a thing. It might be example questions, it might be simplified questions, I might just get partway through a lesson and think, Oh, God, this is pitch. Hey, do I really need to ratchet it back a little bit. So I’ll have the step before up my sleeve as well. For though, for just kind of thinking, No, this is wrong. Or it might be an example. I’ve got partway through teaching something, and actually, they’re completely all at sea with the constituent parts of it. So we need to kind of do a little detour down there. And it might be looking at particular aspects of, of something and we do that before we then go on. So there’s, I’ve kind of anticipated the misconceptions of planned for those. I’ve also planned for the wrong pitch. So I’ve got something for that one. I’ve got maybe something that explores an aspect of vocabulary and something in in slower smaller steps, but most of the time when I’m teaching only here is Tap, Tap, Tap, Tap, Tap, Tap, Tap, Tap, because I’m just literally skipping through the bits that I don’t need.

Craig Barton 26:34

I can only imagine as well it’s quite potentially a powerful thing for the kids like to say I’m skipping through this because you’re understanding exactly where it needs to be on there. So I like this. This is good. This is really really nice. It’s like

Emma Turner 26:45

a buffet rather than a set menu

Craig Barton 26:50

you’re on fire here another great one. I like it. Okay, I’ve uh what is your fifth and final tip you’ve got for us today please.

Emma Turner 26:59

All sorts things. It’s kind of do you want to just a really practical yeah go for organising data. Right so up, Chris such who said you’ve had on recently didn’t want to do something similar for his tiny one of his tiny teaching tips about whiteboard pens and Fritz Stiglitz, never throw a led away. By my doors, the children used to come in. As you come in there was there were two boxes, one with whiteboards, and one with pens and three boxes, actually. A one with pens and rubbers and one with whiteboards in but then there was also a secret, another box there with lids, just lids. And whenever a pen went out, you put the lid in the box and nobody ever lost a lid because there was always a box of lids in the corner. And it makes classroom work like a dream. But I don’t stand people who hand whiteboards out. I don’t understand people who make a big room. Just put them by the door as they walk in, pick it up and come and sit. Pen board. Sit down done.

Craig Barton 27:57

I love it. I absolutely love it. I’ll tell you why. Because that was such a quick Well, let me just ask you one little follow up question about whiteboards. So right now, obviously, we were both big Twitter users and stuff. And it’s dangerous going on Twitter. So sometimes it’s all kicking off left, right and centre. And whiteboards are a real interesting area at the moment, right? Because you get someone like Adam boxer who is it who is has hated whiteboards for many years, but now loves mini whiteboards, and really thinks really hard about the intricacies of using them. And I find it fascinating to listen to him. But then you’ll get like primary colleagues. But beyond that someone will use mini whiteboards all the time in primary This isn’t this isn’t anything new. So I’m really interested here and I don’t want to get any big divide or anything like that. But is how many whiteboards are the absolutely prevalent across all kinds of prime primary primary classrooms and used in a similar way to secondary is your take on

Emma Turner 28:46

Sky flash, something that Yeah.

Craig Barton 28:51

For the benefit of audio listeners, you’ll have to go on the video to see that I was not stuck a middle finger operative, just in case I

Emma Turner 29:01

know that is the National Numeracy strategy for primary schools which came out in 1998. And just kind of rolled out 1999. And many whiteboards were championed throughout that framework and the mini whiteboards kind of started in maths for primary colleagues in the late 90s. And they kind of permeated every part of primary practice, you would be really hard pushed to go into a primary school and not find mini whiteboards. And we use them for everything for quick responses in maths to practising handwriting to making notes for literacy. They are they’re just used for everything, absolutely everything sometimes to great effect and brilliantly, sometimes as with anything just as a rather rubbish prop. But they are woven into the fabric of primary practice and has been for well over well over 20 years that I can’t help but have a wry smile that people have kind of discovered while I was. But going back a little bit, if you have a look at a picture of a Victorian classroom, it’s only a pimped up slate at the end of the day. So, yeah, they are absolutely ingrained in primary practice. And I know that some, some secondary colleagues love them, some loathe them, you’d be hard pushed to find a primary teacher who really hated them. I know a lot of them have got things about lids and pens and just dirty coffee we deal with in primary desktops. But no, they are they are inextricably linked with primary practice and have been for decades

Craig Barton 30:40

now. So amazing. I thought that might be the case. But I wanted to I wanted to hear for you. That’s brilliant. Well, they have been fired. Absolutely amazing tips. super quick, super practical. I absolutely love them. So let me hand over to watch your listeners to check it out of yours.

Emma Turner 30:54

Oh of mine, oh, books. I’ve got a couple out at the minute. So Simplicity’s is out, which is a handbook for primary curriculum and effective primary subject leadership based on a course that I’ve run for about 1215 years now, because there wasn’t anything out there that told you how to be a subject leader or how to actually write a primary curriculum. So I wrote that that’s going really well at moment. And then there is the extended mind inaction part of the Tom Sherrington inaction series, which are written with David Goodwin and Oliver Quigley only, which is out now, which is all about broadening the discussion around cognitive science. So that’s out there. So that’s, that’s a little bit heavier than my other works.

Craig Barton 31:38

Really well. We’ll put links to both of those on the show notes page, so listeners can check those out. Mr. Turner, this has been absolutely amazing quickfire as I say super practical, exactly what I’m looking for. So thank you so much for your time today. Thank you

Transcribed by https://otter.ai