You can download an mp3 of the podcast here.

Jade Pearce’s tips:

- Use explicit instruction for novice learners (02:39)

- How to ensure questioning involves all pupils (14:20)

- Understand the active ingredients of retrieval practice (25:45)

- How to improve feedback (38:45)

- The power of teachers reading research (49:50)

Links and resources

- On Twitter, Jade is: @PearceMrs

- Jade’s book is: What every teacher needs to know

Subscribe to the podcast

- Subscribe on Apple Podcasts

- Subscribe on Spotify

- Subscribe on Google Podcasts

- Subscribe on Stitcher

View the videos of Jade Pearce’s tips

Podcast transcript

Craig Barton 0:00

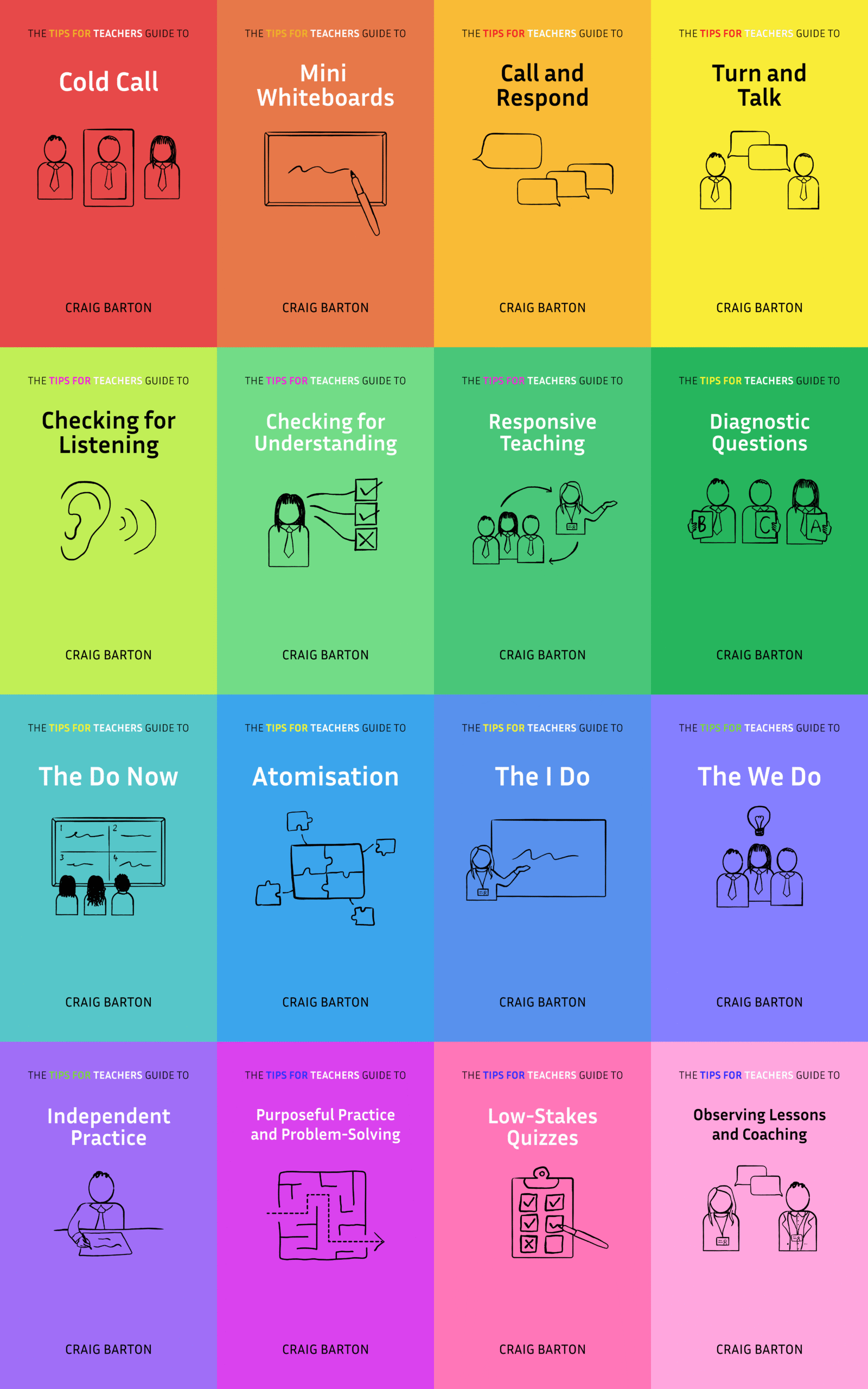

Hello, my name is Craig Barton and welcome to the tips for teachers podcast. The show that helps you supercharge your teaching one idea at a time. This episode I had the absolute pleasure of speaking to assistant head teacher and author of the fantastic book what every teacher needs to know JPS and it is a good one really quick one before we dive in last episode, I told you I’d started recording an online versions of my tips for teachers workshops, I hope to seven now seven out of 10. So available now our habits and routines means of participation, checking for understanding responsive teaching, planning, prior knowledge and the biggie explanations, modelling and word examples. So if you’re looking for some high quality on demand, reasonably priced, just go to my CBD store on your show notes. Anyway, back to the show. Let’s get learning with today’s guest wonderful JPS. Spoiler alert. Here are Jake’s five tips. Tip number one, use explicit instruction for novice learners. Tip two how to ensure questioning involves all pupils. Tip three, understand the active ingredients of retrieval practice tip for how to improve feedback. And finally, tip number five, the power of teachers research as ever, all the tips are timestamps you can jump straight to the one you want to see first. And also at other videos of Jake’s tips are available with tips for teachers websites, if you wish to share them with your colleagues. Enjoy the show. Well, it gives me great pleasure to welcome Jake peers to the tips for teachers podcast. Hello, Jade, how are you?

Jade Pearce 1:43

Hello. I’m great. Thank you. Thanks so much for having me.

Craig Barton 1:46

My pleasure. Right Jake, can you tell listeners a little bit about yourself? Ideally?

Jade Pearce 1:52

Yeah, so I am an assistant head teacher in charge of teaching and learning and CPD at a secondary school in Staffordshire. I’m an evidence lead and education for Staffordshire Rousset school. And I’ve just written my first teaching a learning book. And that is called what every teacher needs to know. And it’s all about evidence informed teaching and learning.

Craig Barton 2:12

Amazing, right? Let’s dive straight in. What’s tip number one, please Jade.

Jade Pearce 2:17

Okay, so my first tip is that we should use explicit instruction for novice learners. And I’ll just go into a bit of more depth on that. So first of all, I go through what I mean by explicit instruction. And by that I mean when pupils are fully guided through the learning process, when the learning processes are really teacher led, I mean that for teaching pupils new knowledge or new content and new skills. And I suppose the easiest way to think about it is it’s the opposite of Discovery Learning where we might require people to discover new knowledge or skills for themselves. And then I’ll quickly go through what I mean by novice learner because it’s something I always get asked when I do a session on explicit instruction. So a novice learner is a learner that doesn’t have a large amount of background knowledge on the topic that they’re studying. Now, what that means is, it’s not necessarily that because you are in year 11, on or in year 13, you’re an expert learner in all of the topics that you’re studying, if it’s a new topic, and you don’t have a lot of background knowledge on that topic, you haven’t done a lot on it before, you are a novice. And and there’s a few reasons why I’m saying that explicit instruction is most effective for novice learners. This is all to do with cognitive architecture and cognitive load. And so I’ll just explain what I mean by that. So cognitive architecture is all about our memories, and the fact that if we look at the cognitive science model of memory, we’ve got our working memory where we process new information, but that is really limited in capacity. And then we’ve got our long term memory, which is basically infinite in how much we can store in the long term memory. And that learning occurs when we move information from our working memories over to our long term memory, so that it’d be caught can be recalled in the future. But and I’m sure everyone listening to the podcast will know this. But if we overload our working memory, if we place too much demand on that working memory and ask it to process too much information at once, it becomes overloaded. And then that transfer of that new information from the working memory to the long term memory is hindered. And we will stay learn that and we’ll all have taught lessons where students have really struggled, and we’ve maybe asked them to do too many steps at once, and then they can’t remember how to do whatever we’re asking them to do. Or we’ve given them too much information, new internet new new knowledge at once. And then they forget some of it. And that’s because we’ve overloaded their working memories. And and what we see with explicit instruction is because it’s very teacher led and because you are breaking things down, you’re always thinking about the amount of load that you’re putting on learners, and therefore it’s more of deaf. Now if we contrast that with Discovery Learning, when we are using discovery learning, pupils have to hold lots and lots of information in their heads at once they have to hold all of the things they’re trying to try what they’ve tried so far where they’re trying to get to. And that places much more load on the working memory. And so it’s more likely to lead to that cognitive overload and cognitive overload and then hinder learning. So that’s the kind of first reason. And then the second reason, and it’s linked to that is that novices and experts learn differently. Now when we’re an expert, we have transferred that working memory into our long term memory. So we’ve got a really good scheme, and we would call it and have knowledge about a certain topic or how to perform a certain skill in our long term memories. And then when we when we then bring that back into our working memory is to use it because we actually need to remember that now we need to think about that content, it only takes up one chunk in the working memory. So it doesn’t cause anywhere near as much load as it would do for a novice learner. And again, for that reason, we need to make sure that we’re trying to be as explicit and guided as guide as possible for novice learners so that they don’t experience that out that overload.

Okay, so like I said, that’s the reason why explicit instruction is likely to be much more effective for novice learners. And then I think we can also look at the issue, the other issues with discovery learning, where we’ve asked students to work out new information for themselves or to work out how to, to solve a problem or perform a particular skill by themselves. And we all have done this. And you can see that there’s, there’s often cognitive overload, that maybe there’s misconceptions, because people think they’ve done it in the right way, or solve the problem in the correct correct way, or discovered this new knowledge, and then they haven’t, and it’s something that you actually have to correct. It takes more time. And it can be more motivating if pupils struggle to kind of discover the right content for themselves. So for me explicit instruction is a really big win. And then I think last, my last kind of point here, I’ll just clarify the kind of strategies that I think, are included in explicit instruction, because your definitions and strategies will differ. So for me, it is chunking. So Blake, breaking complex material into small chunks, and only introducing a small chunk of new information or a small part of the skill to pupils in one go. It’s making sure that your explanations are clear and concise. So you’ve really thought about as a teacher, what do the students need to know? And what’s the most concise way that I can tell them that you’ve used examples to make things concrete, you either use non examples or worked examples if that’s appropriate. I’ll then say modelling including teacher led modelling, modelling as a class deconstruction of exemplar material, or, or example pieces of work, scaffolding for complex tax tasks. So writing frame structure, strips, all that kind of thing. And then extended practice moving from fully guided practice where you are using that scaffolding, and then using guidance fading, to kind of reduce that over time until we get to lots and lots of independent practice. And that’s it. So

Craig Barton 7:56

let’s dive into this a little bit. Now, I’m a bit of a big, big explicit instruction found, but I’m going to play the role of devil’s advocate to Jade. So we’ll see if we can we can dive into this because every time I chat about explicit instruction with reference to maths, I get the same questions back so I never I’ve got so so let me hit you with these questions and see what so the so the first thing is, like, you often get like discovery learning. Very rarely, certainly math Anyway, do you see the weight sometimes presented in research papers very, very rarely will you know, it’s sometimes it’s, it’s held up as this thing where the kids just have to kind of figure everything out for themselves. Whereas what you want you see math and I’m interested if this is true in your subject, is it’s more kind of inquiry based in the sense that students are allowed to struggle for a little bit, then perhaps the teacher comes in with a bit of prompt and a support. And often that’s delivered quite explicitly. And then it’s a little bit more struggle, can they get to the next part on their own, and then followed up by a bit more kind of teacher kind of guided instruction, and so on and so forth. I think that’s the kind of thing that I see more than the kind of, you know, I guess, pure version of discovery learning, would that be true in your subjects? Would that also be problematic in your eyes?

Jade Pearce 9:10

So I agree that that was probably what we see more. And then. And that’s because I think as teachers, we don’t want students to struggle on productively for too long, which is probably the right thing to do, we only have a limited amount of time. And there’s a difference between, I think struggling because you’re thinking really hard about a task or some content and kind of struggling on your own because you actually don’t know what to do. And there are two very different things. So I’d say first of all, that’s a distinction that needs to be made really clear, explicit instruction isn’t making everything really easy for the pupils. It’s being explicit about what the new content is. And actually I found that when you introduce new content using explicit instruction, you’ve then got more time to move on to more challenging material as a class together. And, and I would say that that is still problematic because it still has the issue. Use of stop pure form of discovery learning, where if you’re allowing students to struggle, let’s say maths and you say, how do you think you might solve this problem, some of your brightest kids will be able to work out for themselves. They, especially with your helps if they’re struggling for a bit, and then we help them and then they’re struggling for a bit, and then we help them eventually they will work out the right answer, not all your children will be able to do that. And the ones that are least likely to do that, or those who maybe find that subject more difficult, aren’t as able, etc. And they’re the ones that explicit instruction would benefit the most. So I think that’s probably based on a really common myth that explicit instruction is, I’m just going to tell you everything, and you’re not going to have to think about it when it’s not, it’s not like I’m going to introduce you to the new content. And then we’re going to do loads, practice. But I don’t mean practices in solving the same equation again, and again, I mean, we’re going to look at it I’m Business Studies and Economics. So it might be we’re going to look at how this looks out in different countries. How does this look in different countries? How does it look in different businesses, we’re really going to analyse the benefits and the drawbacks and the evaluations. So I think it kind of allows you to get into much more challenging content and much more depth if you introduce any skills or knowledge explicitly from the start.

Craig Barton 11:15

So write two more awkward ones for you. So next one, I don’t know if you’re familiar with the with the research into productive failure, but this is always the kind of thorn in my side when I’m chatting about this. So for for the benefit listeners who aren’t aware of this productive failure is the notion that you essentially give kids a question that they cannot do, they haven’t got the knowledge to do it yet. But the fact that they struggle with it for you know, five minutes, or whatever it is, means that when you then do teach them it explicitly, they take it in a bit more almost as if they’ve the theory suggests they’ve been primed to it, they’ve already started to kind of activate parts of relevant knowledge and long term memory, and so on and so forth. What’s your take on productive failure as a as an approach? I find it problematic, but I’m interested in your view?

Jade Pearce 12:02

Yeah, it’s a really interesting question. And I would think I can see where the idea behind that would work in that you’ve started to think about, well, actually, what do I know about this topic already? And how can I then use that to solve the problem? I think I will just do that through recapping prior knowledge, prerequisite knowledge, whether that be through retrieval practice, or you explaining it or looking at, well, what have we done previously? And and again, I probably don’t think there’s anything wrong with that. If you’re doing that for a short amount of time, you know, you said five minutes, and then you explicitly explain. And because five minutes, one, you’re not wasting too much lesson time. But also, you’re not going to enable pupils to really develop an embed any of those series misconceptions. So I can see how that would work. And I think if it is that kind of five minutes, it’s probably less of an issue. But certainly, I would just reactivate their their prior knowledge, I suppose.

Craig Barton 12:57

I think I will, too, to be honest. Right is your last one. So this is awkward. So we know that? Well, we we think that explicit instruction is particularly effective for novice learners. And then you get this kind of expertise reversal effect, where once they become an expert, we give them less guided instruction, and so on. So I guess the big question is, when do we switch? Well, when the students go from being novice to expert?

Jade Pearce 13:21

Yeah, really good question. And it’s not something you can quantify, because you can’t say, well, when they’ve got a certain set of questions, right, or when they’ve, I think it’s this is, this is where the role of the teacher in research informed practice is so important, because you have to use your professional judgement as a teacher. And you’ve got to think, do they now have a good, good amount of knowledge about this topic? Can I think you can do it through through that guidance fading? So you know, you’ve done lots and lots of examples together, let’s say or you’ve modelled and then they’ve done some together, they’ve done some part completion questions, once they reach a point where they can independently recite that knowledge, explain that knowledge, show understanding, or performance skill, etc. Without that guidance, and that scaffolding probably that’s

Craig Barton 14:06

fantastic. Right jays, what is tip number two, please.

Jade Pearce 14:12

So tip number two is to ensure questioning involves all pupils, we should use either a whole class response systems, or a combination of wait time, cold call, and everybody, right?

Craig Barton 14:26

Like the sound of this.

Jade Pearce 14:29

Okay, so first of all, I want to explain why I think questioning is so important. And I actually think it’s a really neglected form of part of our teaching that we kind of assume that teachers know how to ask questions. Well, and I think that’s because when you watch an experienced teacher or a teacher who is an expert in questioning, it seems really easy, but actually, you don’t realise the amount of thought and kind of the teacher themselves developing their questioning habits. So I think it’s something which is really overlooked and therefore really important to look at And then questioning we know forms a huge part of assessing people’s knowledge and understanding, allowing for responsive teaching, making sure that you’re correcting any errors or dealing with any misconceptions, but also actually making sure that all of your pupils are engaged and thinking during the cognitive work. So questioning is super, super important. And so because it’s super important, it’s it’s crucial that our questioning involves as many people as possible as much as a time as possible. And so a really popular technique is to use a whole class response system, like mini whiteboards. And I know that lots of people have spoken about that in the past on the podcast, so I’m going to kind of miss over that. And I’m going to say, if you don’t want to use any whiteboard, how else can you make sure that you’re questioning? Just verbal questioning? Doors actually involve as many pupils? So the first thing I think, is that you have to give wait time, or by weight time, we mean the time that you give pupils to think it’s probably I actually call it thinking time, I think it makes it more obvious. The time that you give your pupils to think of an answer. After you’ve asked a question. And before you ask for a response. I think reacher research shows that teachers wait something like naught point two seconds, it’s ridiculously, like short amount of time in between asking a question and then either saying, okay, whoever you know, I’ll take, I’ll take an answer from somebody or answering the question yourself, if no one has put their hand off, you know, we’ve all been in that horrible situation where that’s happened. So we need to massively extend the thinking time that we’re giving to our pupils, and research that I’ve read, so something like three to five seconds for a factual question, but longer if you’re requiring a more detailed response. So if it’s just a short answer, then three to five seconds, but much longer. And if you think how much how often do you do that in your classroom, they’ll tell me when I watch teaching, when I watch teachers teach, there are very few teachers who consistently give that much thinking time. But if you do do that, what you will see is that it allows all of your pupils, not just the fastest thing because it allows all of your pupils to think it gives the expectation, I’ve given you the time to think about it. So you should all be able to come up with an answer. So you get way more volunteers, you get a better quality of response, you you reduce the number of pupils that say I don’t know when you’ve asked, because they’ve had that time to kind of gather their thoughts. So that’s my kind of first age is making sure that you give white time. And then I really like to combine that with everybody writes, and that is essentially what everybody writes down to the question. And I listened to a podcast, it was Oliver Lovell, and Anita Archer. And she was saying that she’d read some research where the quality of responses in doubles basically improves massively. When you make sure that every pupil writes an answer down to the question, you can and you can see that because actually, you you’ve had to really think about what what you think the answer is when you when you write something down. And and also, that forces you to give the wait time because the thinking time, because you’ve got to give pupils time to write an answer to a question. So I would say do that. And then so we’ve given our wait time, either to sue pupils to think in their heads or to write down an answer. And then once we’ve done that, we want to use cold calling. And that’s obviously from Doug Lemov. And that is basically where the teacher selects the pupil to answer the question, not just relying on someone who’s got their hand up, but also that you say the name of the person who’s going to answer after the wait time. So if you haven’t done everybody writes that, again, make sure that everyone is doing the cognitive work, because they don’t know that they aren’t going to be asked. And if you think as soon as you say, Craig, can you tell me to? Well, everybody else apart from Craig has stopped thinking because they know that they’re not going to be asked where if you say, right, this is the question, I’m gonna give you a minute, think about it, or I’m gonna give you 10 seconds, think about it. Okay. Then you ask? Whoever it is, I think that massively increases the engagement. And again, if we look at research on cold call, because there is really, really strong papers that have looked at classrooms that use cold call, pupils feel more confident in their answer, they feel more confident in answering questions, it becomes like comfortable over time, because they get used to it essentially. So do you wait time, maybe get everybody to write and then use cold calling. And actually, I’m going to share an additional tip here and this is one I’ve stolen? It’s not mine. It’s from two teachers at my school who use cold calling with an earache the positive so basically, what you do is you say, right, this is a question and I’m gonna give you however much time let’s say about 30 seconds to think of an answer and when you thought of the answer, or, or an answer, because often like a more open question, it’s not just you know, where there’s one right answer. I want you to put your hand up. And then as pupils put their hand up, you can rate that positively so amazing. I can see two people have already got an answer. Brill, keep thinking if you haven’t, don’t worry about it. If you haven’t got it yet. Just put your hand up when you’ve got one. Excellent. Now foot now now five Have you got an answer? Excellent. 50% did, and you keep going and going, and you get all the benefits of writing the positive about behaviours, where you see it positively enforced, everyone really wants to be involved. It’s the expectation in the room becomes that you will put your hand up to answer questions. So little additional tip from there that I’ve stolen. I like

Craig Barton 20:17

it. I love this right, lots to dive into here. So just a few reflections from me, then I’ll ask you a tricky question, if that’s okay, so, first of all that that wait time, yeah, it always blows my mind when I read the research into that it’s scary. And one thing I’ve started doing now is, as you say, I think three seconds is kind of one of the kind of golden times held up there. So however, whenever I’m ready to ask a child to answer I’ll just try to like, tap out three seconds on me like just to make sure just just to keep it in my head. Because otherwise, it’s so easy

Jade Pearce 20:47

isn’t and it feels like ages, doesn’t it? It feels so long, but you do have to get used to

Craig Barton 20:51

do Yeah, and the second bit as well, I found interesting, um, same research that I read, I think it’s the married board row paper is the wait time after a child’s answered before you evaluate that response. And that that’s a biggie as well, because like, so I say to you, okay, I’m gonna ask you a question, blah, blah, blah. Here’s what’s Pythagoras theorem, Jade, and you told me and then straightaway, I go fantastic, and then move on, you deny in the rest of the kids that opportunity to reflect on that answer, is it the same as what they thought and so on, and so forth. So, but whenever we talk about weight time, it’s always that first one that gets the emphasis. And the second one I get my understanding is really, really important as well. I love this. Everyone writes, I really like that I’ve started messing around with, I’m loosely calling this the holy trinity of participation. I need a better better name for this, but I’ll try and sell you all know that that sounds blasphemous as well, possibly. But I’ll try and I’ll sell you on the dream of it. And then they’ll ask you a question. So I like to do to ask ask is a question. And then everybody writes the response down on mini whiteboards? I like them to do if it’s a long question, like working out on the back, and then like the final answer on the front, so that when they hold it up, I can see the final answer. But they’ve, they’ve kind of written on the back. So I see everybody’s responses. And then so that’s kind of stage one of the Trinity, then it’s discuss your compare your answer with the partner, so you can swap many whiteboards, what’s the same, what’s different, and so on. And then you can either cold call or probably warm call, because you’ve seen some of the responses. So then you can say, you know, Alicia, whatever, tell me about what you’ve got, and so on. And I just like that combo of you get the mass participation from the whiteboard, you get the pair discussion. So everyone’s also verbally, but then you get the advantages of cold call, where you get to kind of build a response with the child, and so on. So I quite like that as I love that. 123

Jade Pearce 22:35

I actually, I actually didn’t put that question in my questioning, because I was thinking, I’m just like, mate, I’m trying to combine too late. It told me it’s not good. I completely agree. I very rarely ask pupils in my classroom to answer questions that they haven’t already discussed in their pair. I think pair discussions are massively overlooked. And actually the confidence that you get from having your answer confirmed, yeah, I’ve got that as well. And then how comfortable you feel in talking about that. And the benefit of reciting the answer. And your explanation is huge. So I’m there with you that

Craig Barton 23:12

I love it. Right. Here’s my awkward question then. So all of this rests on. Like, it’s always one thing, getting our kind of means of participation sorted. But if our questions are crap, we’re kind of wasting our time. And this is hard to do, as you’ve said, so how if we’ve got like a less experienced teacher or a teacher who needs to work on the question, how do you get better at asking good questions?

Jade Pearce 23:32

Yeah, really good point. So first of all, I’d say that it should be part I think of departmental CPD, especially if you’ve got tricky topics, that as a group you discuss what are the most important questions that we need to ask when we’re teaching these topics. So that’s one really powerful way of doing it. Because actually, as teachers, you realise, likely misconceptions, don’t you all, where pupils are going to get stuck or whatever, as you teach your topic, you can pre obviously you can preempt things, but actually, there’s lots of things that come out, and you’ve already taught a topic once or twice, and then you address that straightaway, the next time round. And so I think, definitely taking advantage of your more experienced colleagues who have taught topics before, is really important. And then is is putting thought into it and thinking, right, what actually, do I want to know that the kids understand? And what questions do I need to ask to be able to assess that, and that is a really important skill, but you’ve got to sit down basically. And when I was a new teacher, I’ll write my questions out like script and have them kind of with me, and I’d have right number one, this is the question that I’m going to ask. And then I’d have kind of like strands of sub questions that we’re going to ask stuff after that. So I think it’s just one of those things that takes time and looks natural once you are experienced, but actually, a lot of thought has to go into it. I agree.

Craig Barton 24:52

And just a final reflection, feel free to say anything to this or just move on. The The other thing I find tricky is Well, particularly when I work with less experienced teachers is you think of your question, but then you’ve got to think of that means of participation to assess it, because you can ask a brilliant question. But actually, maybe if it’s requires a long verbal response, you’re only going to hear from one student perhaps. Whereas you could ask, you could perhaps reframe that question in a way that makes it more suitable to mini whiteboards or a diagnostic question or so on. Because you want a good question. And you want as many kids as possible to answer it. And sometimes there’s a bit of a potential trade off, if that makes sense at all between the two. Yeah, completely agree. Yeah, tricky. Tricky. Right jays, what is tip number three, please.

Jade Pearce 25:37

So my third tip is that it is crucial that we understand the active ingredients of retrieval practice. Nice. So why I’ve said that is because we know that retrieval practice is a massively popular strategy. If you I think if you look at how schools are engaging with evidence informed practice where they are, there’ll be one or two things that are most popular retrieval or erosion science. And so, so retrieval is massively important, because it’s one because it has such a huge impact on learning, too, because, you know, it’s got hundreds of yours or 100 years of research, which has proved to be effective for long term retention, but also because of how widespread it is now. And I think that we know, in education, when things become widespread like that there is a risk of lethal mutations. And there’s a risk of retrieval practice not being implemented as as effectively as possible. Where if we understand the active ingredients, and what I mean by that is those parts of the strategy that make it successful, that make it impactful that make it most effective, and have the biggest impact on learning. When we understand those, it’s easier to implement it properly and avoid those kinds of lethal mutations. So, shall I go through what I think the active ingredients are? So okay. So again, I’ve kind of cheated here because I’ve combined lots of tips into one. I hope that’s okay. Okay, so my first point is that retrieval, we know retrieval practice is effective for all learners. And really recent research actually will help to, to prove that to us or to show us that so you’ve got the young Get out 2021, I think it was paper, where they’ve, they’ve shown us that retrieval practice is effective for primary pupils, secondary pupils, post secondary for female and male learners and across a key 80 academic subjects. And then we’ve also got Pooja agar walls 2021 paper, which looked at the research on retrieval practice, but just in classroom settings, and again, found that there’s a consistent benefit of retrieval practice and student learning. So we know that there’s this big impact in all subjects for all pupils. But actually, retrieval practice, to me has got to look different for different pupils in different classes and in different subjects. And that sounds obvious when you think about it, because how can retrieval practice look the same in science than in maths, to English, to PE, to music, to art, like, clearly, there needs to be different things, but also to a child who was in reception to in the fall to in year six to in year 13. So I think we’ve got to be really careful that certainly myself as a senior leader, and other leaders, or teaching or learning across schools, that we allow our teachers to have autonomy so that they decide what retrieval practice best look like, in their subject. So if I’ll give you some examples from my school, in art, for example, their retrieval practice is all skills based. So it’s all practising the skills that they’ve learned previously. And it’s all about encouraging risk and encouraging creativity, not answering five questions on five knowledge, questions on tone or shade, you know, it’s all about practice. Same in PE, you know, it might be that you’re practising a skill that you’ve learned previously even a different sport than then you’ve learned previously. In maths or maths department. It’s all about interleaving, and interleaved quizzes, because we know interleaving has a really big impact in maths not necessarily not the subjects in science. It’s a bit a bit of a mix of short knowledge questions, and they use online quizzing for that, but then longer questions, longer kinds of exam questions. So it should look different in different subjects is my first point. The second point is that retrieval practice must be done from long term memory. And again, this is where teachers have an understanding of that model of memory is super important, because if you understand that, what we’ve done is put in, hopefully, with our teaching is put information into the long term memory, but that we need to practice retrieving that from the long term memory back into the working memory so that it’s not forgotten. Once we understand that we know well obviously that retrieval practice has to be done from long term memory because otherwise it’s revisiting, it’s not retrieval, and you’re not going to get those benefits. So when we first introduced retrieval practice in our school that was about six or seven years ago now, one of the things we realised really quickly, I’d obviously done a rubbish job of introducing it because teachers were allowing kids to use their notes straightaway. Obviously not retrieval practice, you’re using your short term memory or you weren’t, you know, you’re not, or you’re not using your long term memory at all. So making sure that it’s not from long term memory, which also to me actually says that it should be done individually first, not as a pair discussion, because if it’s a pair discussion, one, people will certainly be using less of their long term memory than another if they’re using it at all. So individually and from memory festival, that we know the power of retrieval practice is improved with corrective feedback. So really thinking about right once they’ve done the retrieval task, how are you going to give give feedback so that you are highlighting any misconceptions or confirming correct answers, that it should be spaced from initial learning, and we can look at retrieval strength and storage strength there. And that basically, we need to allow some forgetting so that retrieval strength is lower to get the biggest gains in storage strength. So we don’t want to retrieve information straight away, actually, it’s got to be done after a delay. And that it should be repeated. We want people to encounter those most crucial concepts three or four times I suppose, and that they’re really fully embedded in the long term memory. And that we’ve got to allow pupils to be successful, because otherwise they haven’t actually done the retrieval if you if you’ve given them five questions to answer and haven’t answered any, the class might have done retrieval practice, but they certainly haven’t. So we might use hints or close questions to start off with or cues. But we’ve got to balance that with the need for retrieval practice to be challenging once we make it too easy. And we give too many cues. Again, we don’t get the benefit of that retrieval practice, because we’ve given them too much help and actually haven’t used the long term memories. And then that it should include both factual and higher order retrieval. And this is something that we’ve looked at in MySQL over the last couple of years, because when we first introduced retrieval, it was very much seen as just for factual knowledge, where now obviously, what we’ve seen is that, yeah, that will improve people’s factual knowledge. But it won’t improve their ability to analyse or evaluate or compare or contrast or any of those other higher order skills from memory. And so what we’re moving towards, or what we have moved towards really over the last couple of years is making sure that we’re thinking about right, we might start off with factual recall when we first retrieve a topic, but over time, we need to develop that so that we are expecting people to answer really big questions that combined multiple parts of the course or content for from memory. And that is it for my retrieval practice tips.

Craig Barton 32:32

Right. Okay. This is lovely, this j. So I think the point about the highroad is really important. It’s certainly Matthew, you see that quite a quite a problem quite quite often, I’ve done this myself, where you go a bit deeper when the kids are being taught the topic, but then when you do your retrieval, it’s back to kind of procedural shallow level stuff. So I think that’s a really, really important point. So three questions here. You mentioned that retrieval practice needs to look different across subjects. You also alluded that it looks different across phases, different age groups, Javad, anything more to say on that what what would it look like for younger students versus older students?

Jade Pearce 33:07

Yeah, so I think I for one, I’m a secondary school teacher. So I hope I’m not kind of doing a disservice to any primary experts out there. And I’m sorry if this is wrong, but from from the schools that I’ve worked with, I think that if you are, you know, going all the way down to reception, it is likely to be that we’re expecting a smaller amount of retrieval to be done maybe that you are maybe more concentrating on the factual stuff initially, that asked him some really good stuff. And this was these these ideas are from Emma Turner, so they are not mine I’ve stolen and she does stuff like a retrieval rocket, and they have to like write things that they remembered in their retrieval rocket and she had a spider template as well with like different bits of knowledge coming off the the spiders legs. And so I don’t mean kind of different in terms of we can still ask questions, they can still do a quiz my my daughter’s nine and they do our sticky knowledge quizzes, she calls them. Like, yeah, that’s, that’s retrieval practice. And so you know, where they are be doing some questions about a topic that they’ve taught they’ve learned previously. So I guess it’s the same in terms of the basic mechanisms, but the format, the level of challenge, and the level of support that you give might be different for younger pupils,

Craig Barton 34:22

got it to two more questions. When do you think the best time to retrieve is is there a particular time in our lesson? Is it shifting it to homework? Is it weekly quizzes? Well, what works best for you in your school context?

Jade Pearce 34:35

Good question. So again, we have we allow our departments to decide this completely for themselves. I don’t think there’s a particularly best time in terms of a start of a lesson or the end of a lesson or anything like that. There is research which shows if you switch too much between retrieval and learning new content that can be that can hinder new learning. So again, Yes, don’t switch from all the time. Well, I think that the right, there isn’t a all this is probably the best time, I think it just depends on your curriculum time, what the type of retrieval is, it’s probably, it’s probably important as well. So what we see a lot in our school is that they do factual retrieval at home, because it frees up lesson time, then maybe they do higher order retrieval practice and lessons where, as a teacher, you’re therefore more involved and can give the support to get those really high quality answers. So, I mean, it might object we, I only teach GCSE, you know, level. And we have three lessons a week. And one of our one of our lessons is a retrieval lesson. So basically, they do retrieval practice for homework. And then they come in, and they do a Start Quiz, or a starter activity, because now we’re introducing higher order retrieval. So it’s not always a quiz. And then we go through their retrieval practice homework, and that’s kind of like the single lesson, or the department’s just Do you have a homework or there’s do a start every lesson. So I don’t think there’s a right time.

Craig Barton 35:59

Perfect. And last question on this. And you mentioned, the best time to retrieve is at the point kids are kind of forgetting it most to get this biggest boost in retrieval and storage strength. How much do you go into trying to schedule in retrieval opportunities I use? So kind of, do you think okay, I’ve taught this now. So in one week’s time, I’m gonna ask another question, then in four weeks, how would you spend things out and

Jade Pearce 36:22

soak it all in. So we didn’t use do E, our retrieval used to be very much ad hoc, like, Oh, I’ve haven’t done this for a while, we’ll do that, or I’ve seen a good resource on this. So I’ll use that. Actually, what we’ve moved to now is what we call a retrieval practice curriculum. So you basically had your retrieval practice completely planned out alongside your new taught content. And we give a guide of a round of about four weeks I hate given a figure because obviously, it’s always completely different. But when you tried to be practical for teachers, they they do need some guidance. But then I also say that that will depend on the class, the pupils how difficult the material is, you know how much they’ve struggled with it if it was really complex, and he struggled with it, do it sooner. So we say about four weeks after initial learning, and then you kind of schedule it to recap over the course I suppose, for me at GCSE or the year if you if you’re doing a year group one. But yeah, I think, again, it’s one of those areas where you’ve got to use your professional judgement about what is going to be the point while there, they will remember, but they won’t remember it easily, if that makes sense.

Craig Barton 37:27

Yeah, I think for me that the biggest change has been kind of scheduling in this in advance I was very ad hoc myself, and particularly in math and if you find this in in business studies in economics, there are certain questions are a lot easier to quiz than other things or certain topics I should say. So it’s very easy to include a fractions question in your due now, it’s not quite so easy to include like a rotations question where the kids need a grid and tracing paper and so on. So those topics unless you schedule them in, they don’t tend to be the forefront of teachers mind.

Jade Pearce 37:57

Yeah, I completely agree. And or it’s things that you I do it well, I don’t really like that part of the spec. Just doesn’t jump to that when I’m writing my little quiz. It just never used to jump to mind, or I think it’s probably more resume mentored. And also, I really liked that in the same way of when when you’re writing your talk curriculum, your new content curriculum, really makes you sit down and have some good discussions about what are the most important concepts skills knowledge in our subject that we do want to make sure that we repeat more often what do students struggle with? So that kind of prioritisation, I guess, is a really nice process as well.

Craig Barton 38:34

Yeah, makes perfect sense. That’s brilliant. Okay, Jade, what is tip number four, please.

Jade Pearce 38:40

Tip number four is feedback must improve pupils performance or learning be timely, be acted on by pupils and not create excessive workload. So again, I’m sorry, I’ve got them all in together. So if I think about, I always hated marking, always. So this is I think this is my 15th year now that I’m going into as a teacher, and I absolutely love my job. But I hate marking and I’ve always, always hated it. And that’s because I think when I mark for the first five years or 10 years, probably of my career and feedback was marking you only ever marked it wasn’t actually feedback. It was all written comments. I marked everything as in I gave everything a mark, you know, six out of nine c or whatever the grade was, and then wrote some comments on the bottom. It took ages it was always massively delayed because it took me two weeks to get round to mark in that pile of books. And you give the kids the book the kids the books back and you’ve just spent that last night you know, three hours the night before sat marking, and they don’t even read the comments, you know, because it actually they see oh, I’ve got about nine doesn’t matter what she said because a guy and I or I got four out of nine. Oh my God, that’s rubbish. I didn’t want to see what she said. So and I hated it for that reason that it took so much time and I just didn’t What I was ever getting bang for my buck, I guess in terms of workload. So where now, I kind of say the changes that has come along in my practice and the practices my school. So first of all, I rarely give marks to pupils. That doesn’t mean that I don’t, I might record a mark in my mark Bach, but actually pupils, you know, we’ll do three kind of more summative assessments for our data captures at school, and I’ll mark those properly, to see how they’re getting gone. But now, feedback is about improving. It’s not saying how well they’ve done what they’ve done. And initially, kids really struggle with that. And kids, you say, but Miss, what have I got? I say, right. Okay. Let’s say it’s an essay in economics, and it’s a 25 mile cost essay and I say to you, you’ve got 20 to 25. What does that mean? Because we’ve done loads of the work together, you’ve only just learned the content, you know, I’ve modelled a paragraph for you, then you’ve written it, it’s not in time conditions, you haven’t remembered off by heart, you’ve used all your notes. So it’s not really a true reflection anyway. And then even if it is a true reflection, even if you’ve done it as a timed essay, what does 22 out of 25 mean, it’s not an A level paper, it doesn’t mean that you’re going to get an A, because who knows what you’ve got in the rest of the paper. So it’s trying to really show pupils that when you mark their work, the point is not to tell them how well they’re doing, it’s to give them feedback to improve. And then it doesn’t matter how well you doing, because we’re all going to get better, essentially. So moving away from marks, only formative comments, massively feedings forward. So essentially giving feedback before they do the task. And by that will mean scaffolding modelling practice, etc. So the idea there is that pupils know how to complete the task to a good standard before they do it. Well, what I used to do, and now I’m like, I cannot believe I did this is you’d let them write an essay, let’s say, and then afterwards, you told them what was wrong with how they wrote the essay. And I think why did I do that, that’s obviously a ridiculous thing to do. So making sure that they know that beforehand. And then really moving towards either live marking, or you’re marking the work and giving feedback as pupils are completing it. And they’re making the changes immediately, or live whole class feedback. So we’ll often do a paragraph or part maybe one question, and then I’ll say, right, let’s have a look, let’s get some kids works under the visualizer. What’s really good about this brilliant, add that into your work, how could we improve this work? Excellent. If you’ve made the same mistake, can you improve that for me, please. So it’s, it’s all about that kind of instant feedback. So they’re improving their work that that little bit of their work, but then obviously, you hope that they improve the rest of the work that they were going to write with the feedback. Or if you are going to live give delayed feedback massively. Now we depend on hopeless verbal feedback. So taking the work and having a read, making a note of common misconceptions, common errors, really good bits of people’s work that you want to share. And then I found that, because we’re the best will in the world, if you are marking 30 books, 30 pieces of work, and you’re writing, the most you can write is two or three comments, isn’t it because even if you’re willing to spend your entire evening marking that sort of work, the most you can write is two or three comments. We’re actually when you give whole class verbal feedback, the amount of the feedback and the quality of the feedback and the depth of the feedback that you can give is so much better, because you don’t just have to say something like, You need to analyse this further. You can say this is exactly what I mean by analysing further this is an example of when we haven’t analysed this as an example of we had when we have analysed, right, improve your work for me, please. So just massively more beneficial. And that’s, that’s my feedback now, based on that tip.

Craig Barton 43:36

Right, this is nice. So a couple of another biggie and a couple of things that dive into here. How does that play out in in other subjects? Are there any subjects that find that model or approach more difficult than?

Jade Pearce 43:49

Yeah, so definitely, I think English, I think modern foreign languages for similar reasons. In that obviously you are, may be more concerned with the quality of written work. But I think that’s a misconception. The misconception on a whole classroom of feedback is that you’re not picking up on things like spag because you just given kind of general stuff, you still should be. So you should still be taking a note of Spark. And then if there’s a pupil who, let’s say, hasn’t used capital letters, just write their name down. You don’t have to write on their word, use capital letters, although obviously you could do, I would just write Joe, capital letters. And then I would say to Joe, in the next lesson, haven’t used capital letters, correct it for me now, please, before you start anything else, and again, if there’s, you know, spelling mistakes or anything like that, so I think, I think that’s really important. But what I would say is, again, this is all about teacher autonomy. And we now at my school have no requirement for written feedback. So you do not have to give written feedback. But if as a department you decide actually, there’s these however many pieces a year, three, six pieces a year, where we want to give written individual feedback, because we think in this case, it’s going to be really beneficial, and that’s fine.

Craig Barton 44:58

Interesting, interesting, um, I’m really interested in obviously, you’ve got two perspectives here, you’ve got you as a teacher, but also as a senior leader. And when I work with the law schools and obviously, I just chat about maths, this you still you still get schools that have to take in books every two weeks or whatever mark would teach them arts or the classwork, right, all these comments and you get things like Gordon, well done, and all this kind of stuff. And the kickback is always well, SLT need evidence they need evidence and so on and so forth. Are you What’s your stance on this? Or are you not concerned about that as

Jade Pearce 45:35

one? What do you need evidence of, because if it’s, I don’t want to see written marking in books, because I’m like, that is evidence that you are wasting your time. And that actually, you’re probably not giving good quality feedback, because you’ve written two comments there. And unless you’ve combined that with verbal feedback, they’re not that clear, actually normally, about how to improve their work, you know, use more description, well, if the kid could have used more description, they would have done that. So unless it’s, to me, written feedback is often poor quality, and not as clear what the pupil has to do to improve what I want to say. And we do look at books we don’t take books in. But we look at books, when we go, you know, drop into lessons, what I want to see is that there’s a good quantity of work, that there’s good quality of work, that there’s evidence of, of challenge, I want to see evidence of the things that we know are effective. So is there evidence of modelling? Is there evidence of self assessment? Is there evidence of verbal feedback, which is then being acted upon? I don’t have to see the teacher, you know, writing verbal feedback in the margin, because if it gets corrected their work, they’ve used feedback to correct that. So I think it’s just thinking about what what are you trying to evidence? And it’s not necessarily written feedback, which would be the best evidence for that anyway. That was never wrong.

Craig Barton 46:54

No, it’s good. No, it’s really good. And if I’m just gonna take this opportunity to ask you a bit of a curveball question that’s related to what we’re talking about when we’re not necessarily to feedback about books. So often, again, when I visit lots of schools, there’s always different policies knocking around for what has to happen in box, right? So some schools, it’s got to be lesson objectives, written out, title, date, all this kind of thing. Now, whenever I talk about using tools of mass participation, like mini whiteboards, or ABC cards, or whatever it may be, or lots of pet discussion. One of the kickbacks I often get is well, we can’t do that because SLT wants to see evidence in books. And if they if they look through a book, and they saw today, the only thing written down is like a worked example. But everything else has been done on mini whiteboards or discussion. So it’d be it’d be a problem. So where do you stand on that? In terms of kind of what what for you is SLT would you like to see in books? Or is there a minimum you’d like to see there?

Jade Pearce 47:50

No, I am honestly not bothered what I see in books, I want them. I want this really sad. I think that pupils are denied those learning opportunities, because it’s not written down in a book, I can’t believe that, that still happens. It’s a it’s a really narrow view of how learning occurs, I think and on what, why don’t work astounds me that we’d have to provide written evidence of our pupils learning. Now, there’s nothing I want to see in books. And actually, we don’t have books across the school. Some departments use folders, some, some do use books, it’s completely up to them. And I just think you want to see, not necessarily in books, but because it’s more I think, going into lessons and talking to pupils, you want to see evidence of learning. And by that I mean, long term learning, because if you’re looking at a book, what are you going to look at? Oh, it’s neat. Well, okay, I get that that might show pride, and it might show high expectations, absolutely fine. They’ve done lots of written work. They’ve completed a worksheet, what does that mean that they’ve completed a worksheet does? Do they actually understand it? They did that four weeks ago? Do they remember it? And actually, those things are much, much more important to look at when you’re in lessons, and so much more evidence of learning that you can talk to a child and they can say, at the moment, we’re learning this, this is what it is linked to this that we’ve done in the past a few weeks ago, we did this did it and then the fact that they’ve got a nicely filled in table in their book, for example. So I think we’ve got to understand the difference between performance and learning. We’ve got to be brave and trust our teachers, I think is the most important thing and give them autonomy. And realise that learning isn’t necessarily what they’ve written down in the books was what they spent the whole lesson copying that off the board. How much learning had they done? They’ve got a lovely book loads of notes in but probably zero learning. I guess. Sounds a bit ranty too. Sorry.

Craig Barton 49:46

No, by kinda. That’s brilliant. Right Jade, what is your fifth and final tip, please?

Jade Pearce 49:50

Okay, so it’s a bit of a different a different one. Because not related to a kind of individual teaching practice was something that I think is super important. I’m super, super passionate about it. And that is the power of teachers reading research. So when I first started when we I guess as a school actually first started our journey towards evidence informed teaching and learning, as a leader, leader, our teaching learning, I saw it as my role to read everything and then kind of distil that, whether that be in a CPD session or and I used to do a really long Teaching Learning newsletter, which no one ever read, or that kind of thing. And so now, whilst I still see it important that actually teachers are time poor, and there’s very few of us who want to go home at night and read recent papers, read research papers, I mean, I do, but there’s not that many of us that want to do that. So I still think it’s important that we are distilling research for teachers, but also I think equally is important is that we’re giving teachers to read teachers time to read research for themselves, I think it leads to a much better understanding of evidence informed practice, if you read something for yourself, and much bigger commitment to evidence informed practice, if you’ve read research for yourself, it promotes the idea that reading research is the norm, we’ve got an amazing culture in my school now where we’ve got teachers who regularly read research who share blogs, we’ve got, I’ll go through some of the ways that we’ve kind of made sure that teachers can read research, but just a really great culture of a middle leader came to me the other day and said, Can I set up a middle leaders research group where we’re going to read research about middle leadership and house How was best to lead quality assurance in your department, or how best to lead CPD in your department. So we’ve got that kind of culture now. And I think you only get that when you start reading research, we will all have, at some point in our career not had been that interested or not having engaged that much with evidence informed teaching and learning and with evidence with research, you get that little spark, don’t you and you read one thing, you want to read another thing, then you want to read another thing. So I think that initial engagement makes that more likely to happen. And then actually just kind of helping me, it means that you’re not always standing, standing up and saying, well, the research shows or the research says, and actually, teachers are getting that from another voice. And it gives much better credibility to what to what you’re then saying. So I’ll try and give some practical ways because that all sounds like amazing, doesn’t it, but I’ll try and give some practical, practical ways that we can do that. So in my school festival, we’ve got a teaching and learning research group. Now that’s a voluntary group. And we meet once every half term. And we read a piece of research and I send out some questions in advance. And actually, I think that’s really important, because it gives teachers confidence that they feel prepared, especially when you’re starting off, it’s quite daunting to read, you know, quite heavy articles sometimes. So publish the questions in advance. And then we meet and we discuss that as a group. And we talk about well, how is that going to impact our teaching. And then this year, we also have done that with pastoral research group that isn’t led by me it’s led led by some of our pastoral leaders, and they meet and read research regarding pastoral issues. And then like I said, from September, we’ll have our middle leadership one starting as well, which will be great. We do what what I call Flexi insect sessions at my school. So two of our inset days every year are disaggregated. And you accrue the 10 hours during the school year, and you can have those two extra days off. And so one of the things that you can do to accrue those hours is to attend a research session where it’s very much like the Teaching Learning group, but you you’re just recruiting growers, so you call him you read your piece of research, you discuss it, and you bank an hour. And we also for that those hours, allow teachers to do independent reading as well. So I publish a reading listening to our Teaching Learning priorities, we’ve got a really good CPT library, which are advertised with, you know, some information about what you might read if you’re interested in a certain area of pedagogy, but then also stuck in contact me and say, I really want to know about, I don’t know interleaving in maths or

homework, effective homework, and then I can suggest some reading that they can do. So we’d all know things. And then we also do a teaching and learning Inquiry Group. And again, that’s voluntary, and that is where we normally focus on one aspect of teaching and learning. And it’s normally something that we’ve identified that we want to focus on as a whole school. So last year, yeah, that’s just finished, we looked at questioning and checking for understanding, because we noticed that that needs to be a whole school priority for us from September. So basically, I do a reading list and each member reads a piece of research on the reading list. And then we meet in the first meeting or discuss our findings, share the strategies that were kind of advocated by the literature that we’ve read, you choose two or three things you’re going to trial in your teaching over the year. And then we meet kind of regularly to evaluate that say how it’s going. And then at the end of the year, we produce a little guide. So that’s really nice, because next year when I introduce questioning as a as a whole school priority, we’ve got 25 members of staff who already have been focusing on that for a year. And but also we’ve we’ve trialled things in our own contacts and our own subjects with our own people. So we’ve kind of put together a Best Practice Guide. That’s it.

Craig Barton 54:56

Wow. That is That’s brilliant. Okay, I’ll love this I love I love the fact how you structure this. And I love the fact that you make time for it that feels like the most important component of this. I like that incentive as well to bank your hours. And just couple of questions here. How do you choose which papers to kind of direct staff towards? Do you have any kind of criteria that you use?

Jade Pearce 55:20

Know, it’s normally stuff that I have read that I think links in really well with something that we’re focusing on in school. So for example, when we’ve looked at retrieval practice in the past, it might have been the young paper or the Ag wall paper on Bloom’s Taxonomy, taxonomy showing that we need higher order retrieval practice. It’s not always research papers, it might be parts of like the great teacher toolkit or papers like putting students on the path to guided learning, where it’s not necessarily a research paper, but it’s a kind of a journal article. So no, I just tried to find things that I’ve read and found useful. And because we have like a CPD curriculum, where we try to focus most of our CPD on our Teaching Learning priorities, so that we haven’t got loads of people focusing on loads of different stuff, we’re kind of driving towards these things that we’ve identified as being most important. I basically suggest, though, a number of things under each heading five or six things under each priority, whereas if you are working on retrieval practice, or challenge or literacy, these are the things that will be most useful to you to read.

Craig Barton 56:21

Got it? Got it, I’m gonna ask you one more question. And I’ll give you a bit of time to think about it well, so I’ll just shut away for a second, I’m going to ask you to pick out a couple of papers that have had the biggest impact for some of your staff that you’ve suggested. The reason I asked, this is what one thing I wanted to do with tips for teachers, and I’m really pleased this is happening is that people are sending him around the videos of the tips. So for example, at inbox, so with these mini whiteboards, or recently, Chris such on literacy, and that can be quite nice thing, you’ll watch a five minute video seven minute video on this. And then let’s discuss that in a departmental meeting. Because often you’ll get people who’ve distilled the research into into hopefully quite an accessible way. So I like videos and medium alongside audio and alongside reading as well, too, as a way to share this research around. But yeah, anything sprang to mind in terms of kind of big hitters have been big.

Jade Pearce 57:09

In terms of kind of more general things not linked to a specific aspect of teaching. I’ll definitely recommend the great teacher toolkit. I think that’s really extensive in the amount that it covers. I would say in terms of like the cog size stuff done last year 2013 paper, and then there’s actually been a recent one hasn’t that by Hattie where he’s kind of looked into more depth about the findings. So that’s really interesting kind of addition to that. Putting students on the path to guided learning is a really nice accessible one about explicit instruction. And then the longer paper to that, which is why just why? What is the title of it? It’s not on my head. Why Discovery Learning harms learning I can’t believe I can’t remember it, cuz I must have read it. But that one is really nice.

Craig Barton 57:59

Yeah. Minimal guide. Yeah. Well, I

Jade Pearce 58:02

mean, minimally guided instruction, harms learning, I think is what it is. And then in terms of we’ve we’ve looked at cognitive load, and the cognitive load theory, research that teachers really need to understand, you know, the kind of New South Wales I think it is green green booklet is really good. So I think this depends, there’s some general things right and trans principles is obviously very general has lots of implications for lots of areas of teaching and learning. And then I think you’ve got to look at your individual priorities, and there’s lots of papers that would link specifically to each one of them.

Craig Barton 58:37

Got it. Fantastic. Well, Jay, this has been absolutely brilliant. There’s been huge areas we’ve we’ve covered a lot the way you’ve sneakily tipped off Ah, that’s brilliant. So let me hand over to you what should listeners check out of yours

Jade Pearce 58:49

Okay, so I’m you can get me on Twitter and I’m at PS missus on protect because So Mrs. PS. And my book like I said at the start is out for preorder now, and it’s released on the fifth of September I think and that’s probably like lots of this stuff today is obviously from from the book and the most important things I think about teaching so that as well.

Craig Barton 59:14

That’s fantastic. That is brilliant stuff. Well, Jade, this bill, absolute pleasure. I’ve wanted to get you on the show for a while. I’ve followed you on Twitter for a long time. So this has been really, really loud. So thank you very much for taking the time. Thank you so much for having

Jade Pearce 59:25

me.