You can download an mp3 of the podcast here.

Ollie Lovell’s tips:

- How to overcome the limits of working memory (03:39)

- Backwards plan. ALWAYS backwards plan! (22:16)

- Check for understanding (34:03)

- Inquire into mechanisms (44:25)

- You can learn something from everybody (57:43)

Links and resources

- On Twitter, Ollie is: @ollie_lovell

- Ollie’s website is: ollielovell.com

- Ollie’s podcast is: the ERRR podcast

- You can buy Ollie’s book, Cognitive Load Theory in action, here

- And his book, Tools for Teachers, here

Subscribe to the podcast

- Subscribe on Apple Podcasts

- Subscribe on Spotify

- Subscribe on Google Podcasts

- Subscribe on Stitcher

View the videos of Ollie Lovell’s tips

Podcast transcript

Craig Barton 0:01

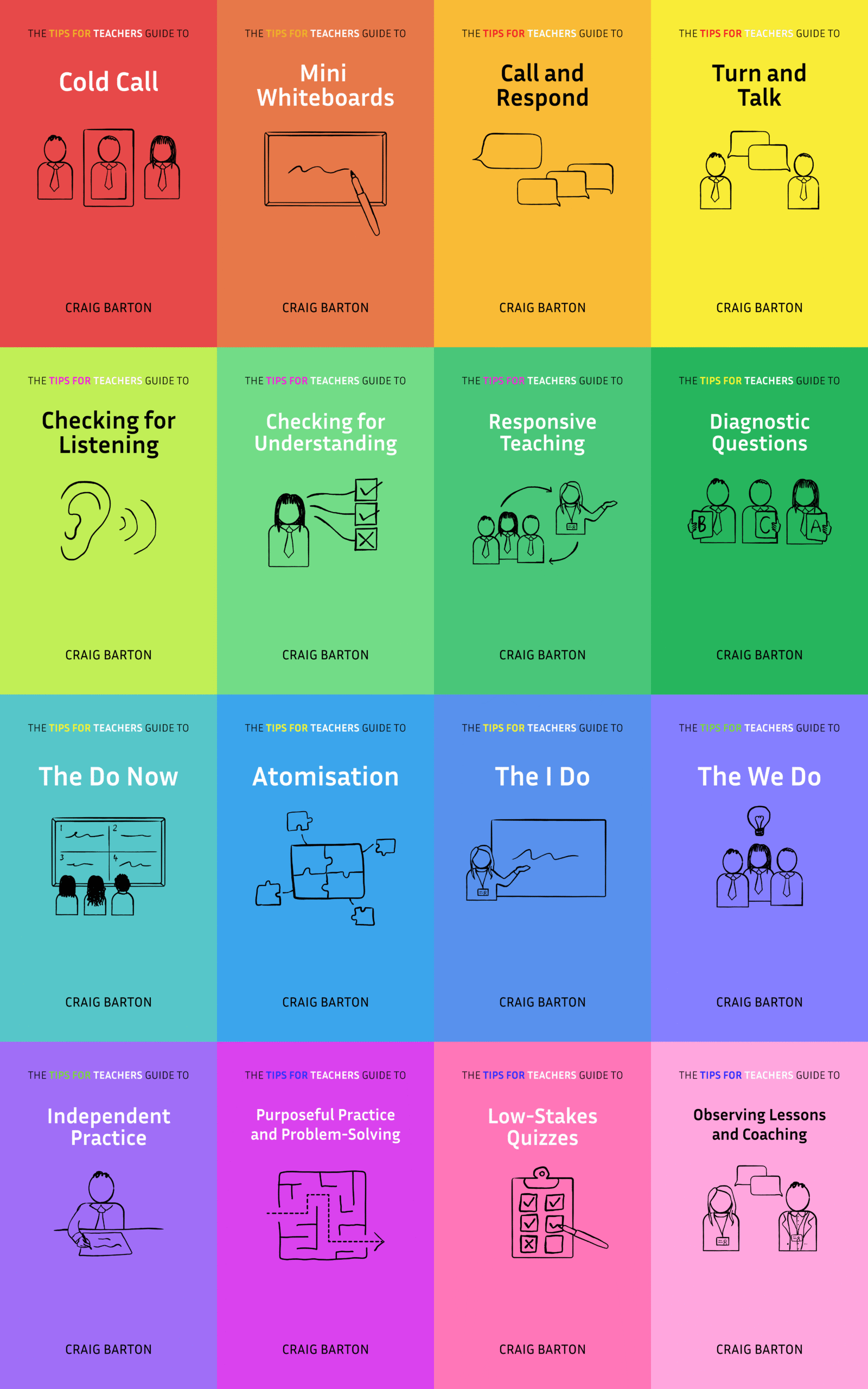

Hello, my name is Craig Barton and welcome to the tips for teachers podcast, the show that helps you supercharge your teaching one idea at a time. This episode I had the absolute pleasure of speaking to teacher, author podcaster. And I’m gonna say it global phenomenon. I’ll leave two pieces of news before we hear from our way. First, a reminder that I’ve now completed the recording of all 10 of my premium online on demand tips for teachers workshops. And here’s the list of the 10 workshops those habits and routines. And number two is the means of participation. It’s one of my favourites when you are checking for understanding responsive teaching, planning prior knowledge. The biggest one explanation is modelling your words examples. Then you’ve got a workshop on student practice, memory and retrieval and homework market feedback. I’ve spent ages recording these the form of short, sharp videos, links to research links to resources, and they’re all available at a pretty reasonable cost. So they’re available on my online CD store. You’ll find a link to that on the tips for teachers website on that CPD and secondly I’m dead excited about listening to the teachers book is released on the sixth of January 2023. At this contains over 400 ideas to improve your teaching the very next time you step into a classroom. The production team at John CAPP done an amazing job, a beautiful looking book. Again, there’s loads of links to online resources and stuff in there. So if you’re interested in either pre ordering or ordering this, depending on where you’re listening to it, again, you’ll find a link on the tips and teachers website under the book section. Anyway, time for me to shut up. So spoiler alert, here are all these five tips. Tip number one, the limits of working memory are only overcome by chunking and automating into long term memory. Tip two, backwards plan, always backwards plan. Tip three, check for understanding. Tip Four, inquire into mechanisms. And Tip five, you can learn something from everybody. As ever, all the tips are timestamp so you can jump straight to the one you want to listen to first. And videos of all these tips along with all the tips from the tips of teachers guests are available on the tips of teachers website if you want to watch the video and share them with your colleagues enjoy the show.

Well, it gives me great pleasure to welcome Mr. Ali Lovell to the tips for teachers podcast. Hello, Ollie, how are you? Good.

Ollie Lovell 2:41

Thanks, Craig. How you doing?

Craig Barton 2:42

Very well. Thank you very well. I’ll eat for the benefit of listeners. Can you tell us a little bit about yourself ideally in a sentence?

Ollie Lovell 2:49

Sure. Well, a little bit about myself. I’m very confused because my face is being recording, not just my voice.

Craig Barton 2:58

I like it. I like it. It was a bit more I’ll give us

Ollie Lovell 3:02

Yeah, Teacher teacher in Melbourne, Australia, four days a week at the moment, while I do a few other things like run the education research Reading Room podcast, which is why I’m used to having my voice recorded but not my face. So I do strange things in my face. It’s weird, weird old habits. Sorry listeners and watchers in particular. Yeah, I teach maths as you do and have, Craig. And it’s always always a pleasure to have a chat with you.

Craig Barton 3:30

Looking forward to this one I’ve done well to had to go through your many PR agencies to get you these days. Are you getting big these days, but I managed to get a little bit of your time. So I’m very grateful for that. Right, let’s dive straight in. What’s tip number one?

Ollie Lovell 3:44

Tip number I’m not used to such such a little intro Craig, I’ve got to get on my horse straightaway. Alright, tip number one. Now, this is kind of a takeaway, there’ll be familiar to people who are familiar with my work. And that is the limits of a working memory are only overcome by chunking. And automating information in long term memory. So the kind of background the background of this one is essentially I when I was at school, I was always of the view that like why would I need to know anything? Why would I need to and particularly you know, I mean history when we were learning dates and things like that. I was like this is an absolute waste of time. Wasn’t until about 2014 When I started to learn Mandarin Chinese and get a bit serious about my learning and and read Dan Williams, why don’t students like school that I learned about this whole working memory long term memory thing? Now? I don’t know. What’s the level of background knowledge of listeners of this Craig, tell me if I need to go into things or if people if everyone’s already knows about the limits

Craig Barton 4:44

of Whoa, give us it always, always good to have a refresher. Anyway,

Ollie Lovell 4:47

I’ll Okay, great. So, and you timestamp all the all the takeaways as because I’m a listener. So I know people if they’re bored, they can jump straight to the next one. So human cognitive architecture. We can think of it in three main components there’s external. So this is the, or the environment, this is where everything is, this is where our ugly mugs are, Craig, if someone’s watching this or listening to our voices, it’s where the internet is. It’s where books are, it’s where colleagues are. And it’s an unlimited external store of information. So people can can access as much as info as they want, without able to access in the environment, when they people pay attention to information in their environment, can make its way into their working memory. And working memory is a limited internal store of information. So depending on whose research you look at, if you look at Miller’s research, it’s seven plus or minus two kinds of elements and, and associated interactions at any one time. And then when we think about things, when we sleep on them, when we connect them to things we already know, and things like that, that information can make its way up into our long term memory. And when it’s in our long term memory, that’s when we kind of say it’s been learned. So the thing is, you know, the odd the odd part out in terms of this whole architecture is the working memory, because it’s the actually the only limited store of information within this whole store of new information within this whole kind of architecture. And what that means is that when our students get overwhelmed when they get confused, and things like that, it’s usually because there’s some sort of overwhelm of their working memory. But then the question becomes, what if if students can only hold about seven plus or minus two things in their working memory at any one time? How can they why can they do more next year than they can this year? And why can they do more the year after that than they could next year, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera? And the answer is by chunking. And automating information in long term memory. And chunking just means we take multiple elements of information. For example, we take the letters in, in memory, M E, M, O ry, they’re originally a number of elements, and then we chunking them into a single word, and we can use that word flexibly, and then we chunk the word memory into long term memory, which then becomes a concept, which then we can use flexibly. And so this, I mean, for people who are familiar with this, this is covering old territory. But for me when it was new, this was absolutely revolutionary. Because I had always thought that noise was a bit of a waste of time, you know, I thought I was a reasonable thinker, I thought I could come up with creative ideas, yada, yada, yada. But it was only really when I learned well, actually, this knowledge is the foundation of all higher order thinking and, and more and more complex and deep thought is actually just more and more knowledge, integrated and interacting in better and better ways. I thought, wow, this is phenomenal. And I completely changed the way that I live my life, I started to be much more focused about building knowledge. And I started to use technology like Anki to try to memorise things. And and if I’m honest, I’m in terms of my ability, like in terms of what’s helped me to kind of build the knowledge required to continually run the podcast first to write sales and action and to write tools for teachers. In many ways, it’s because I’ve had such a commitment to just not forgetting stuff over the last 789 years or so. So that’s kind of that’s kind of the level one of the of the takeaway, I guess the level two of the takeaways is my my learnings since then, I feel guilty for using that word learning’s because I saw Dylan William, tweet on Twitter yesterday, something like, Is there is there a more aggressive word than learning’s? I’m asking for a friend. I didn’t follow the thread. But I thought, oh, no, I’ve got to stop using that word, but it’s probably too ingrained. Now. Anyway, I guess the more recent learning, for me in relation to this is is how important it is for knowledge to be connected in really authentic ways. So since I kind of learned about the importance of, of knowledge stored in long term memory, and in addition, the importance of kind of repeating information spaced repetition to build and consolidate that knowledge, I’ve kind of gone on this whirlwind, like cram stuff into my brain kind of a kind of a journey. And along the way, there’s been a lot of frustration and, and a lot of forgetting, and, and it’s taken me many, many years of trying to cram stuff into my brain to realise that, actually, there’s only so much that you can take in, and it’s only really the stuff that you you’ve in transfer you then apply you then relate to other new things and it kind of forms this like connected chain of knowledge that you can continue with building upon, that it actually becomes ingrained and part of that long term memory in a way that you can use usefully. And so I’ve you know, had to abandon various learning projects along the way. Recognising that I have just enjoyed reading Oliver Burke, Berkman is forfeit 4000 weeks Craig, recognising that you know there isn’t infinite time in our lives and To do some things well, we have to kind of reduce other things. And you know, a further thing. example that is like yesterday someone said, Ali, I was running a pay day they said, Allah, you do the podcast you teach, like, how do you fit it all in? And I said, I have no idea about like any sport in the world. I haven’t watched the sport match for many months. Don’t know what’s happening in the rest of the world. In terms of the news. I listened to like the news radio for five minutes, like the summary every morning, but that’s about it. And I don’t know my family’s names now that’s a guy with far but but really, I cut out I’ve just cut out a lot of stuff because because there isn’t time for it. But but also the The final thing about this is that I think that when we do recognise the importance of like these interconnected, progressively built knowledge structures over time, I think that might even raise questions about the way that we kind of structure school and the kind of breadth we expect our students to cover. And then expected to stick and expected to stick in meaningful ways. That yeah, that’s that’s that’s amusing. More than a conclusion or a tip.

Craig Barton 11:08

Love Ally Love it, right? And three things for me on this just to dive into thirst. I’m interested in how this practically plays out in your teaching. So how does this what you’ve learned about the limits of working memory, the importance of connecting knowledge? How does that change what you do day to day?

Ollie Lovell 11:25

Well, it really just means that I try to build in and I’m lucky enough to the school that I work at is very good at this as well, we try to build in really structured ways for students to re encounter core information, core ideas, but also not just kind of re encounter them actually retrieve them, and use them in practical practical ways. So I mean, something that I’ve been talking about a lot in like peds that I’ve been running recently is the benefit of daily reviews. And if you’re looking for someone, if you’re in a primary setting, and you’re looking for someone who does a really good job of this, David Moore Kunis has a great video on YouTube. So shout out to Dave. And if you’re in a secondary setting, there’s lots of different apps and stuff like you know, an inbox carousel, or there’s pudsey, which I’ve been using a bit recently. Or there’s just kind of making your own. So it’s really about trying to give students enough exposure to content over time. But also another thing is, is giving them and like helping them to overload it, and especially overload, like the core content. Because that helps really, really better down.

Craig Barton 12:30

Cool. Okay, just two more things on this. One of my kind of things I’m thinking about a lot at the moment, I’ll let it come back at me if you think there’s a load of rubbish is I think as a profession, we’re a lot more research informed than perhaps we have been certainly when I started teaching them, certainly things have shifted a lot in the last 10 to 15 years. But I think there’s still a bit of a gap from so the research has gone from kind of the studies to the teachers, but I’m not so sure it’s found its way to the kids. And I think as teachers, often we do a lot of things, but perhaps our kids aren’t aware of why we’re doing them and the reasons and so on. So I just wondered, how do we get our kids on board with this? Like, is it important that the kids realise the limits of working memory and so on? Or is it is it just more important, and we just do things in lessons that take account of that?

Ollie Lovell 13:16

I actually think it’s super important. So the podcasts I did just before my most recent one was with a group of two teachers, and a researcher, the two teachers are from Chechi grammar, church, your grammar is like super focused. I don’t know if you saw that episode, Craig, but Jeju grammar is super focused on teaching, or developing self regulated learners. And they’ve got like a four year programme that teaches students about retrieval, practice spacing, all these kinds of ideas, but they use like student friendly language. And, you know, in the research, we call it informed training, it’s basically training people but informing them at the same time, like what you’re training them about, and why you’re training them about it. And it’s, it’s to me, it’s like, it’s the most interesting frontier within education. It’s what I’m doing my PhD in at the moment, because I think it’s just we need to get it right. And it’s, I’m also really excited that the school I’m working on at the moment Brighton grammar over the next couple of years, it seems like we’re going to look into this space a little bit more in a bit more of a focus way. I’m super excited about that.

Craig Barton 14:23

Fantastic. And final question on this. Now, we’re recording this in the start of August. And so I think it was I think it was July, Tom Sherrington put out a really good blog that I know you retweeted and I did as well about quizzing and retrieval practice and how it’s become a bit of a lethal mutation that you know, there’s everyone thinks to do and retrieval practice lots of different ways of doing it. And one of the things that came up from Tom’s blog that really rang an alarm bell for me is this idea that kind of disconnected knowledge is not necessarily a good thing. You know, take your question on 10 Completely different areas. Is it is not, you know the way that we want students thinking about retrieval practice. But then think about how I might start a lesson off with, you know, four questions on four different areas of maths or how I might do a low stakes quiz, where I want 10 different topics from 10 different areas. And I think, Am I doing the wrong thing here? Am I? Because this knowledge isn’t connected? You know, there’s a question on fractions of the question on area and so on. Do you think is math just different in this sense? Are we okay to do that? Or is it something bigger going on here? And and how does it play out in your lessons your retrieval practice?

Ollie Lovell 15:31

So so on that connection point, I would say the important thing is not that the five questions they’re doing on a particular day are linked to the other four questions or the content of the lesson. It’s about the connection to the students prior knowledge. So if if we have five questions, which are meaningfully related to things that the students already know, such that they are able to actually retrieve the content and have a successful retrieving episode, or retrieval episode, or that when given a few tips or hints or working through with a teacher or a partner, they can build upon something that they’ve got stably in their long term memory, then I think that is meaningful, meaningfully interconnected knowledge. And that’s can be a valuable learning activity. I think the challenge comes if if that knowledge isn’t kind of bedded down sufficiently first, second, third time around such that the students really do you feel like this is five questions, all of which they have no idea what the heck they’re doing. And then they just kind of get demotivated or struggled to see connections that could be saying, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. So I guess that’s the way I’d say it in terms of what it means in for my own retrieval. It basically just means that I’m constantly adapting the kind of questions that I’m giving students based upon what I’ve seen, in prior lessons to try to make sure it’s in that kind of Goldilocks window of bringing stuff back. So it’s a little while ago, it’s not wasn’t just necessarily last lesson or the easy thing. But but more importantly, than the time break, it’s actually that kind of retrieval, strength break and in in a zone where there’s a bit of effort to retrieve it, but it’s not so hard that it’s out of reach.

Craig Barton 17:22

Got it makes perfect sense. Let me just check one more thing, before we move on to tip two. Another thing I’ve been thinking loads about retrieval practice. So Kate Jones has been on the show, and obviously, she knows infinitely more than than I do about this, I’ll tell you mistake I’ve made Oh, and I wonder whether you’ve either can relate to this or whether you just think what what has he been doing here? Right. So let’s imagine you’re teaching summer for two weeks, whatever it may be straight line graphs, fractions or whatever. By the end of that two week block, you would hope that you’re going a bit deeper into the concept, you’re asking students much more challenging questions, maybe they’re generating their own examples, maybe you’re weaving in other areas of maths, or the contextual stuffs coming in all that kind of stuff. But my fear, then is when we jumped to retrieval practice, so whenever I want to review fractions in a in a do now or low stakes quiz, I seem to by default, jump back to the procedure. So I dropped back to you know, just adding two fractions together, whatever it may be. And my fear is that students only ever go deep at the time when they’re studying the topic. And then retrieval becomes almost this kind of shallow level of knowledge. So what I’ve been trying to do now is build in a variety of questions into retrieval practice. So you do now it may have a couple of procedural questions in there. But also, then it’s going to have either a problem solving or a generating examples, or give me a boundary example, or a non example of this, and so on. Because my fear is if retrieval is always this procedural, shallow, shallow level stuff, the message we communicate to kids there isn’t great, right? It’s, you know, this is the only level you need to learn this. So just just to kind of thought and reflection of my own poor practice, does that resonate with you at all?

Ollie Lovell 18:52

Yeah, that’s really a good, really good point, Craig, I guess my thoughts on that is that retrieval, the function of retrieval can be thought of in a few different ways. And, I mean, this is something that I’ve learned from my own language learning, right? So I’m learning I mentioned learning Mandarin before, I’m trying to learn the German at the moment. And what I’ve found, like I use a spaced repetition software called Anki, it has like, you know, word like phrases in German with a missing word. That’s it, then in English, and I have to retrieve the German version to complete the sentence in in fully in German. And I find that those cards are usually created, they’re created by me from a rich learning environment. I might be listening to a podcast and might be reading an article or a short story or news article, something like that. So it comes out of content, it comes from context. Then I take it out of that context, and I create kind of retrieval cards for myself. Initially, it’s quite a quite a meaningful card because I can kind of remember the story, but over time, the context kind of falls away and it becomes this like, disjointed, like, abstract by it. self’s kind of thing unless it’s from like quite a meaningful chat or something like I’ve got a few cards I made from my recent trip to Germany and, and I think they will retain their context for a bit longer. But it’s also understanding like, how much to expect from retrieval practice. So what I’ve learned is that Anki with language learning is absolutely fantastic for keeping the knowledge of a word, kind of at the edge of my retrievability, such that when I do actually encounter it in a proper context, again, it’s not like it’s a completely pardon the pun foreign word, it’s actually, it’s actually of like, Ah, I know that word, or there’s a level of familiarity. And then I, when I, maybe I just need to check the definition, or maybe I hear it a couple of times in a couple of different sentences. And that’s enough to for me to get Oh, that’s right, it means this thing. And so I often actually see retrieval, as a bit of a placeholder to kind of just maintain this base level of familiarity with the content such that, you know, when we do spend, you know, 15 minutes on it to, in an in an like, in a, in a good classroom contexts, say you’re going to teach another lesson where you know, you’re going to actually draw on that, in this example, vocab, in the maths example, some some other skill, you can quickly activate it, activate prior knowledge, and then you can build upon it. Whereas if you hadn’t done that retrieval in between, the strength of that memory would have degraded so much that you wouldn’t have been activating prior knowledge you’d be re teaching. And so that relates back to the comment I was making earlier, in terms of like the scope of learning that we expect. And the rich enter retrieval can be seen in some contexts, unless, unless it’s really, really thorough, but if it’s a quick thing down at the site, it can sometimes be valuable to see it as like a main maintenance kind of a task for that knowledge. Which is only worthwhile though, if you’re actually going to build on it later. Because if you actually don’t build on it later, then it does become this completely disconnected and irrelevant piece of information. And quite frankly, a bit of a waste of time, because students will forget it.

Craig Barton 22:15

Alright, so what is tip number two, please?

Ollie Lovell 22:19

Do number two is backwards plan, always backwards plan. So this is the first level of this level, one of this tip is, is for people teaching to high stakes exams, right. So in my first year of teaching, I came into a school, there were very few resources. And I had to try to work out. It was actually my second year that I started teaching year 12, which is like the high stakes year here in Australia, I had to work out really quickly what on earth, I needed to teach my students for them to be able to have success in the interview exam. A similar thing has happened happened to myself when I was like at uni and I was doing a couple of subjects. And either there were clashes, so I couldn’t go to the lectures have one or I just been completely slack and left it till two weeks before the exam to try to work out what’s going on. In both cases, there’s there’s kind of there’s there’s a common a common approach, which is in the lecture scenario, like, go through all the lectures, or read all the chapters in the textbook, and then try and perform the exam or in the teaching example. Look at the curriculum, try to work out what’s going on, look at the textbook, use that and try to prepare your students using those resources that other people, ideally experts have created to prepare for the exam. But I am this may be this may be obvious to some people, but over the years, it’s taken me a while to realise that, actually, the hurdle, the bar we’re trying to jump over is actually that examination. And this is obviously in the restricted sense of teaching. But but when we are focused on that particular goal, hopefully we’re balancing with others. But when we’re focusing on that goal, that is that’s the bar we got to jump over. So backwards planning essentially just means work out, do a massive audit of what is in past exams, and use that as your teaching guide. So what this looked like for me, in that first year teaching year 12, and I had very little support to do it is literally printing out single sided, a whole heap of past exams like that 10 years worth physically cutting up every single question. And then, you know, getting on the math staff room floor over one weekend, and just moving them into piles that seem to make sense and be related, and then sequencing those piles and then relating those piles back to the study design. And then when I looked at the study design, and it had some strange thing, like, you know, making make adjacency matrix from a network diagram or something like that, I could go, okay, ah, that’s actually what they’re talking about. This is a thing, or it’s some other abstract point where you’re like, Well, that could that could be taken to eternity. You know, you could keep on analysing that idea forever. But it’s like, well, actually, they’re actually, they’re only going to ask you to analyse it in three different ways. And so by doing that, I was able to very, very quickly ascertain exactly the level of difficulty that was required of my students with the level of capability that was required of my students teach to that, and have a reasonable amount of success in that first year of teaching, and similarly have a reasonable amount of success in my uni subjects, even when I had slacked off on a couple of them throughout the semester. So that’s the that’s the kind of level one of this takeaway that I think the level that level two of this takeaway is when we do broaden out the question of what are we black backwards planning to? So I think the application of that backwards planning idea was very crystal clear when we think about an actual exam but but you know, what’s, what’s the goal of school? I don’t know. But one of the kind of goals is to prepare students for life more broadly. And if we backwards plan from life to school what is it useful for the majority of students to know so I don’t know I’m actually curious to ask you Craig in the last month or two what maths have you used and you know, talking blasphemy hear people say Get ready? What what maths have you used in your real life?

Craig Barton 26:20

Or flipping that call? You know, I’m supposed to be asking the questions here. Are you not allowed to just spring the spring these on? Well, I’ll tell you what, I can give a bit of a cheat answer only because I’ve been doing a lot of maths with my little boy Isaac, but that’s kind of in a bit of an inauthentic context. We’ve we learned about negative numbers this morning. absolutely blew his mind. So that that was nice. But in terms of terms of day to day maths, not counting on my YouTube viewers for this to project outward. So yeah, well, I’m going to hit some certain milestone, but not not not a massive I do quite a lot of recreational math. Sorry, I’m a bit of a geek with that kind of stuff. So I like that kind of thing. But I wouldn’t be doing that much kind of authentic maths, I guess day to day, how come?

Ollie Lovell 27:02

I’m just I’m just trying to backwards plan from life as to what we should be teaching, for example, disengaged your nine year nine students, you know, like, what should we be like? So I actually you know, I’m as I’m sure you do, I use I do use maths in my life, I kind of did a bit of brainstorm before I checked today. One of the one of the areas is around financial stuff, the idea of mortgages and amortisation. I think about a fair bit. And so I need to have a general sense of what’s going on there. Investment and debt are hugely important issues, I was chatting with a friend the other day, and they were trying to work out whether to pay off some loans or not. And the basic principle there is, you know, do expect that the money you’ve taken out on the loan, can you earn a higher return than the interest rate, and if you can, then maybe keep the loan, if you can’t, then probably pay it off. Time, time is really important. And a lot of people struggle with time to just telling the time, percentages, and the ability to use them, heaps ratios, the ability to use them. And, you know, dimensional analysis, I don’t know if this is something people have heard of, but just the idea that you can actually use the unit’s from a question or a scenario to help you work out how to work it out. Um, that’s something I actually use fair bit when I’m working at the prices of things or various ratios. And then the final thing is like spreadsheets, I use spreadsheets a hell of a lot. I’m always summing stuff up. I’m also always doing other weird stuff that like concatenation, and weighted averages and things like that. And, you know, lots of teachers use a lot of those functionalities as well. So, yeah, I guess for me like this, this idea of backwards planning, level one helps us to jump through hoops, and helps our students to jump through hoops. But level two, helps us to ask which hoops should we be jumping through? And which hoops you would be trying to help our city or hurdles? Should we be trying to help our students to jump over? And as a weekly, you know, this isn’t a criticism of particularly anything, the primary curriculum, I think, number sense, the things like that is absolutely crucial. And the way that primaries generally do that is is really valuable. But I think secondary, there’s some questions that should be asked, and it’s pretty, pretty productive to ask those questions. Yeah, but, I mean, again, this sounds like blasphemy. So to approach it one other way, that people who think I’m talking blasphemy might find valuable, it’s the quote Dylan William. And that’s to say that education is about opportunity costs, right. So it’s not about whether it’s valuable for your nine to learn trigonometry or your nines. No doubt it is. The question is, is there something that they could be learning that will be more valuable during that time? And I think I think that’s a question we don’t ask enough. And I think it’s a question asked worth asking. The answer might be well, actually, no algebra is the best use of trigonometry or whatever is the best use of that you know, in time, but I have a I have a sneaking suspicion and maybe not, and maybe not for the whole math curriculum that we have. So so that’s that’s the thing I’d love listeners to keep in the in the back of their mind. It’s not an argument against maths of the value of maths. It’s an argument for a conscious consideration of opportunity cost.

Craig Barton 30:16

Love it. All right. Okay, one, one reflection and two questions on this. So first, this was bad, right? So I remember, however, many years ago it was, I got asked to teach a new app, something I never taught before foot further, further maths was what our kids do. years 12 and 13. And I’ve never taught further maths before, I was always dead excited to do it. But the way I decided to teach it was the opposite. Well, the way I planned it was the opposite of what you did, right? So I didn’t look at any exams. I just had the textbook, and I tried to stay just kind of one chapter ahead of the kids. So the only exposure the kids would get to practice was the practice questions from the textbook. I know he got to the exam, we started doing pass papers, and it was nothing, nothing like the textbook whatsoever. And I’m thinking bloody hell anyway, we it turned out, okay. But the next year, it was very much exam focused, it was very much yeah, let’s let me get a sense of what kids need to do. And you see this with experienced teachers, right. They just know how to pitch things. They know what to put emphasis on, and what not to put emphasis on because they taught a course for many years. The flip side of that is a few years ago in the UK, our GCSE. So the exam our kids take at the end of year 11, the spec changed for that. So nobody had any exams to go off. And the exam boards would release a couple of kind of sample papers. And then you had a real dilemma because you have a real small sample size of things to go off. So do you just put all your eggs in one basket and teach, you know, to the kind of standard and the way these questions are styled? Or do you just kind of think, no, we don’t that’s too small, a sample size? Do we just do what we’ve always done and hope it still works? And it was it’s a real dilemma. So having having a big batch of those final summative tests is is really beneficial. But the flip side of that Oh, and this was the first question I want to ask you is how does that play out for lower years? So you know, your, you know, grade threes? Grundfos, they don’t have the this end of year exam? How do you know how to how can you backwards plan with them?

Ollie Lovell 32:12

It’s a good question. I mean, and I’ve done a bit of this in schools, it’s, I just keep on going backwards, basically saying, you know, we’ve we’ve identified what are your twelves need to be successful? What prior knowledge do they need such that when students come into your 12, when they’re exposed that content, it’s not going to be too big of a jump, and you just work your way backwards, that becomes the kind of core stuff that you know, like to create successful, quote unquote, students, when we talk about in terms of marks, that, you know, if we build our curriculum based upon this, it’s going to be successful. And then depending upon how rich you feel, that is how much time additional time you feel, feel you have, you can add in the the other stuff that you feel is likely more important or equally important. But hopefully, if exams are written well, the content contained within them represents the kind of key ideas and concepts from a domain such that if you do eventually backwards map from that all the way down to down to your seven or something, you’re still going to get to have a lot of quality content there.

Craig Barton 33:17

Got it? And final question on this all? Does this this strategy that was planning? Does it apply on the kind of per lesson basis as well? If you were thinking of teaching a lesson? Would you start at where you want the kids to get to at the end of the lesson and go from there? Or does it not? Does it not kind of transfer down?

Ollie Lovell 33:33

Yeah, so it’s like Oliver Caviglia, always good about this. It’s like put put ideas in containers or concepts in containers and sequence them along a path. So the concepts will be those parts exam questions, you put them in containers of related concepts, then you’ll sequence them along a path, which will become your kind of learning sequence. And then you basically just step cut that up into bite sized chunks that represent lessons. That’s that’s kind of the way to look at it.

Craig Barton 34:01

Fantastic. Right all what’s tip number three, please.

Ollie Lovell 34:06

Tip number three. So tip number three comes from, I’ve talked to lots of people over the years on the trip law podcast. And when I, I’ve asked quite a few pretty switched on people, including like, Tom Sherrington, what’s the absolute most important thing for teachers to do? And the answer is, check for understanding. Okay, if you’re not checking for understanding, you’re not working out the difference between between what you think you’re teaching and what your students are actually taking from the lesson for thinking about this in another way, Dylan William has essentially dedicated his whole career to checking for understanding that’s basically what formative assessment is, but they’re not just checking for understanding actually acting on the data that you collect from that checking for understanding. So I mean, what does that mean practically? It just means things like aux cord means mini whiteboards. It means stuff like Desmos. Teaching students to check understanding for themselves means stuff like up I had Paul Spencer Lee, a science teacher on the podcast, helping students to analyse the types of areas they’re making, things like that, you know, there’s teacher checking for understanding peer and self understanding. Great, great quote from Dylan William in a recent podcast is good feedback Wirtz works towards its own redundancy. So checking for understanding, in a way and supporting students to check for understanding in a way such that you don’t need to keep on doing it for them, but they start to do it for themselves. Coming back to that learn to learn kind of thing we were talking about, is really valuable. So that’s kind of the level one, this takeaway, the level two, helps us understand why it’s really so important. Check for understanding is the basis of working out what works in education? You know, if we think about what is a research study, a research study is essentially a systematic approach to checking for understanding, you do something for to one group, you do something different to another group, then you check for understanding to see what works. So if we do nothing else, if we never teach teachers in teacher education, how to do anything, we only taught them to check for understanding, they would derive pretty much every instructional principle that we have in every technique, because they would know what’s working along the way. And they would know what’s not working. And step back even further check for understanding in many ways is essentially the science the scientific method. So at the classroom level, we need to check for understanding what’s going on in our lesson. But it that process, that cycle of trying stuff out and checking if it’s actually working is the basis of all learning, both inside and outside of education.

Craig Barton 36:53

Love it all biggie. This one right. Okay, so a few things from me here. So first, just a reflection. I think you’re right. One of the things you said early on really resonates with me this, the response to that check for understanding, if you’re not doing that, you might as well not bother with a check for understanding. And when Joe Morgan was on the tips of teachers podcast a while ago, she said that whenever you go to CPD about responsive teaching and checking for understanding, the emphasis is always on the check for understanding it’s not so much on the responding because the responding is that odd, right? Like if you’ve got half the kids know it, and if your kids don’t, that’s when you’ve really got to think what you’re going to do. So yeah, if you’re going to check for understanding, preparing in advance how you’re going to respond for different scenarios feels feels really, really important to follow up questions on this whole. So you mentioned lots of different kind of mechanisms for checking for understanding cold call mini whiteboards, and so on and so forth. And this this often comes up a lot on the podcast, particularly mini whiteboards. If there was a drinking game on the tips for teachers podcast, it’d be have a shot every time somebody mentions mini whiteboard after the album, box or episode, everyone would be everyone would be hammered. But the thing that we think about a lot here is why if you had many whiteboards available, so you could elicit responses from all your kids. Would you ever cold call? Where’s the argument for cold calling if you can get all the responses?

Ollie Lovell 38:14

That’s a really good question. I haven’t thought about that before. And it’s relevant to me because I do both use mini whiteboards. And I cold call things I think I’d say it depends upon timing. Like how much time you have, it also depends upon the type of answer. So many whiteboards are great. In a like time press scenario, when you’re doing like multiple choice questions when you’re doing single answer questions, single word questions, things like that. The pace of the lesson kind of slow and things can get bogged down a little bit as soon as you start doing like extended written answers. Now, mini whiteboards are excellent for that because you can overcome the trends in information effect and you can take a student’s written answer you can put it under a dock a visualizer project up on the board and add to it and and go through it. And that’s awesome as well. But also, I think there’s a there’s a benefit to getting students to verbalise their thinking to vocalise it, and it kind of enables a bit more of a dynamic kind of problem solving, a discussion and refinement in the moment, as well. So yeah, and also, you know, if, if you’re trying to just quickly go through, like, often, I’ll often use cold calling when I’m actually doing like a second worked example. So I’ll do the first worked example, explain every step. Then I have my pop six in one hand, and my marker and the other. And I’ll do the first line of working and say, What am I going to do next, Craig? And Craig will hopefully tell me, that’s exactly what I follow. What am I going to do next? Based on the first work example, Harry and Harry will tell me. So I think it’s really good for that snappy stuff. Whereas if I said, what’s the next step? Everyone meaning whiteboards, it’d be like 30 seconds later, you know, what are they going Right, divide both sides by three or a symbol or like, you know. So I think there’s that kind of, in the moment just keeping everyone engaged kind of pop stick thing that I really like using, but then it’s like, okay, well, not all now we’re going to do a you do. And we’re going to check if like 80%, or more of the class knows before I set you on independent work. And then I know who to follow up with, or I know if like lots of people don’t understand. And then I can go through another couple of examples.

Craig Barton 40:26

Got it? Fantastic. I’ve actually just a couple of two bonus reflections before I asked you this last thing. First is I’m a big fan. Now I call this the holy trinity of checking for understanding. I love this now. So it’s the combo of you ask a question. I like the kids to do if it’s like a more extended thing that working out on the back of the mini whiteboards, and then the final answer on the front of the whiteboards and then I’ll say, okay, 321, hold them up. So I get a bit of a sense of what’s going on. And then without me evaluating it in any way, then they discuss with their partners compare what’s the same, what’s different, and then I warm call based on what I’ve seen on the whiteboard. So you’re getting almost, it slows things down. But you’re getting the best of all worlds, you’ve got the whole class response, you’ve got the pet discussion, then you go because I agree with you. The big advantage for me of cold call is you get that verbal interaction, they can refine the responses as well, well, so I love that I’m going to pay to them that that I think Holy Trinity is a phrase has been taken already. But if I can get the holy trinity of checking for understanding, I think we’re laughing there. Second thing I was gonna say this is a big, big shout out to you ally for one of your interviews. And also your excellent book. Was it who was a neater Archer, who was talking about the importance of we do and I always called out the way do you know what I’m doing? I do in a word to them, I always go from one example to your turn straightaway. And it was only when I listened to that conversation. And in particular, I found powerful when I read your book, and you almost kind of scripted out an example of a we do, where you can really play around with the different means of participation, a bit of call and response, a bit of maybe mini whiteboards a bit of cold call, I thought that was really powerful. So as a key check for understanding within the words example process, I think the we do is really important. But the final question I was gonna say to you is and it relates back something we discussed earlier on Ali, do you think it’s important to vary the types of questions we ask when we check for understanding because again, I’m guilty of this, I use a lot of diagnostic questions. And they’re quite, they’re very good at identifying single steps and multi step procedures, you can do a bit of a conceptual stuff as well. But it’s more kind of procedural. Or if I do like mini whiteboard stuff, as you’ve alluded to, it tends to be more of a kind of procedural question. And I just fear Same with the retrieval that unless we’re kind of testing the depth of understanding by varying these questions around a bit, maybe we’re only getting a sense of that kind of surface level. So where do you stand on kind of different types of questions you asked to check for understanding?

Ollie Lovell 42:50

Yeah, so good question. And again, not something I’ve thought about heaps. But I think maybe that’s just because it’s kind of different concepts and different understandings lend themselves to checking them in different ways. And this is this kind of back to that extraneous versus intrinsic, cognitive, kind of an idea. It’s a question of asking What the What’s what’s intrinsic? what’s at the heart of the knowledge that we’re trying to check for understanding because you’re gonna get that, and then that’s then going to determine how you’re going to check, check for that understanding. So some things if they’re if it’s more of an interrelated, interrelated, kind of a concept that has multiple moving parts, you probably need some kind of verbal, kind of dialogic thing or some written response. Whereas if it’s, if it’s literally what’s the first step? And why that can be a diagnostic question. But I think also good question is in any scenario will always always probe. So you know, that a misconception is revealed. And then the probing will start into with exactly the root of that. And that helps to direct how the kind of responsive teaching follows, because if you just like, Oh, yep, you’ve picked B, that means you have? Well, to be fair, in diagnostic questions, it probably does actually just mean that they have that misconception. But even then, asking a student to articulate it can help you to kind of hit it off even even more directly. So I think, I think to summarise the content determines how to check for understanding.

Craig Barton 44:23

Love it. Right. So what is tip number four, please?

Ollie Lovell 44:28

Tip for? You mentioned previously mechanisms. So Tip Four is inquire into mechanisms. So you might have when you might have tried something in the classroom. Or the your school may have mandated that you do something in the classroom, and you may get a good result, or you may get a bad result. Usually what we do there is we say, oh, that worked or oh, that didn’t work. But inquiring into mechanisms is essentially a nudge for us to go a bit deeper and to actually ask The why. So, for example, I mean, an interesting example is using your kind of sign worked examples, Craig. You know, it’s like, okay, I do sign worked examples, and students learn more. That’s, that’s cool. Like, if that’s the case, but we need to, then we can then ask the question, why is that? Is it because they have increased focus? And there’s there’s less distraction in the classroom? What if so, maybe actually, there’s a better way to do that than being silent tonight? Is it because they’re actually systematically following every step of working that you’re doing? Is that the active ingredient, if so, awesome, but maybe there’s a better way, maybe Michael person’s approach is better. Maybe there’s actually the silence, maybe there’s something about silence that helps students learn maths. I don’t know, in which case, you couldn’t take that silence away. So so when we inquire into mechanisms, we actually work out what part of the thing that we do is most likely to be generating the effect. And this is really valuable. It’s valuable be for a number of reasons, it’s valuable because it helps us to make more love, more reliable predictions of the future. Because if we know what the active ingredient is, we know if taken out, it’s probably not going to work as well, as it allows us to modify strategies and approaches without lethal mutations, which is a phrase that gets bandied around a lot these days. But, you know, a recipe is very, very good in a stable environment. But unfortunately, teaching is not a stable environment, different students, different days, different weather, different cohorts, different amount of sleep that you’ve had, and all these things are factors. And if but if we’re aware of the core part of what we’re trying to do that generates the effect, we can actually adapt what we’re doing in such a way that it’s hopefully has the intended effect, even through those adaptations. And in relating to adaptation, it enables us to save energy time resources, because maybe there’s a strategy we’re doing that has 10 steps, some feedback approach, or whatever it may be. And we know we’ve been doing it for five years, it’s it always gets really good at action from the students or responses from the students good learning. But maybe there’s only three of those steps that actually have have an impact. And we’re doing all these other things like cutting up the staples, or using different coloured highlighters, that’s actually a complete waste of time. So So that’s, that’s, that’s that takeaway, I can’t remember what we’re up to 4345. Now, inquire into mechanisms. That’s a level one. Level two of this takeaway is, I don’t actually know what a mechanism is. So to expand on that, one paper that talked about mechanisms a lot. Last year, October of last year, was won by the E FF from by sans themes. And their definition of mechanisms, a phrase that they use interchangeably with active ingredients was an active ingredient is a component of PD that could not be removed or altered, without changing the impact of the PD on teaching and learning. Now, that sounds sensible, that’s kind of relates to what I was saying. But does that mean that oxygen is an active ingredient of PD? I definitely agree that if you remove the oxygen of the PD, that would likely change the effect. But oxygen itself is like an entity. It’s like an element within it’s not is it a mechanism, I thought that the mechanism is something about that, like causality. So maybe it’s about the connection between. So that’s confusing me a little bit, then I thought, Alright, maybe I know that a really good way to describe mechanisms is with like, if then statements. So if we were thinking about cold call, I gave a presentation at this step lab conference recently, I was trying to look into the we’re trying to dissect the mechanisms of cold call. And this is one of the definitions that was come up with using the if then framework, if students are sufficiently motivated to appear knowledgeable to the class, then knowing that they may be asked a question at any time will drive them to engage with with it and prepare an answer. Right. So that’s one approach or another approach with describing mechanisms using the bias statement, which is I think, Bambrick Santoyo. So coming back to cold call, sustain a high level of student focus throughout the lesson by making it unpredictable when the students will be asked a question, right. But then when I started to think about and dissect that more, I mean, those things, they seem pretty clear. It’s like make sense. Part of the mechanism of cold call another one is the check for understanding part, of course, but then I then I started to think, well, maybe there’s is there actually anything different because then between a mechanism and just having a goal and a step? So the goal could be help students attend to instruction more and the step is, make it unpredictable when you’re calling them like what part of the goal versus step is the next And isn’t isn’t like the in between part? Is it? How they come together? Is it? I don’t know, Craig, I’m confused. What is the mechanism? So I think some other hypotheses I had were like, maybe it’s maybe it’s your ability to answer a number of why questions in between. So that shows you’ve got on samples kind of like this. I don’t know. I’ve read a lot of stuff about mechanisms recently. And I think they’re really important. I just don’t really know what they are. But maybe that’s love, you know, love is really important, but like, What the heck is love? So maybe mechanisms are important with love? I don’t know. Anyway, that’s my that’s the level two, I’m confused.

Craig Barton 50:38

Who were going deeper like this. So again, usual thing one reflection for me then then one question. Something, yeah, he hits home really early on, I’ve done this lots, you change too much. And you just you can’t I mean, even changing one thing, it’s hard to identify what impact it’s had to Dissector. But as soon as you start changing two or three things, it’s just a disaster waiting to happen. And I have this myself, you you listen to a podcast like your own or you go to a CPD session, get two or three different ideas. You think, right, I’m going to implement those tomorrow. And then the lesson either goes well, and you don’t know why, or it’s a disaster, and you don’t know why you’ve changed too many variables. So certainly, it feels before we get to the nitty gritty of mechanisms, it feels important just to narrow that change down to just one thing if possible. And the second kind of reflection before I ask you, the question is also sometimes when we change something, almost inevitably, when we change something, we have to stop doing something else. And I think that often gets overlooked a little bit, we may inadvertently stopped doing the one thing that was making all the difference. Sound teachers a good example of this, it may be that the teacher is speaking at that initial exposure. 20 amble is the key thing. And if we take that away, and replace it with sound teacher, maybe sound teacher brings another benefit to it. But we’ve removed a really key thing. So it’s always worth reflecting on what. And sometimes it’s hard to spot what have we taken away here to replace it with it with this new idea? But here’s my question for you all with with all the fact that you confused about these mechanisms, and I don’t have a bloody clue, I can tell you that much for free. What do you do when you’re instigating a change? Then what what’s your what’s your process? Let’s say you listen to a podcast or whatever, or you read some research, you want to change something? How do you go about doing it? And how do you know if it if it works?

Ollie Lovell 52:21

It’s a good question. I think it’s just coming back to maybe that thing I was referring to at the end there. It’s like to what extent can you suggest a potential causal connection between the proposed action and the desired outcome? And if you can say that, yes, there, there’s pretty clearly a causal path here. And you can articulate that causal pathway, which is something you would have seen me write about a little bit in tools for teacher as well, if you got to that chapter, then I think the mechanisms there. But I guess the confusion, for me is like, not whether a mechanism is present or not, but more about like, what part of the causal chain between action and outcome constitutes the mechanism? Is it the whole thing? Is it the step, the mediation? Is it the moderation? Is it the goal? Is it the action? I don’t know?

Craig Barton 53:13

It’s interesting, there’s just just just one final reflection on this all and it’s really interesting, you brought up sound teaching here, because sometimes I see two different things going on when you try and bring in silent teacher. So the first is often you get like a honeymoon period, where the kids because it’s so novel, they’re just like, What is this and their full attention is on it. So the danger there is you do this one or two times you think I’ve cracked it, this is the revolution I’ve been waiting for. But then obviously, the novelty wears off. And the maybe kids go back to being a little bit more disengaged, and so on and so forth. So I think when you bring in something new, be aware of the honeymoon period. But then also, I think we talked about this last time, when you were talking about tools for teachers on my Mr. Biomass podcast, this notion of this value of latent potential, when you bring in a new idea, often there’s a, there’s a, there’s a big lag before you start see the benefits of it, because it’s not been embedded. And students are really focused on the structure of the idea versus the content of the idea, and so on. So that’s just to add extra complications, right? When you when you try and make a change, you’ve got to be aware of this honeymoon period and aware of this kind of, you know, valley of latent potential. So you may only see whether this is work, and it may take a month or something like that. And if it’s not working, that’s a month gone by, you know, where, you know, the opportunity cost you kids could have been doing something more effective. It’s tricky, isn’t it? But yeah, have you considered that this this honeymoon, and this latent, potentially feels like they’re two kind of competing factors that come into play when we try and make a change?

Ollie Lovell 54:40

Yeah, yeah, it’s huge. And I mean, that relates as well to another really important point about mechanisms. And that’s the Hawthorne effect. So this is something that found it a lot of studies, simply by the act of conducting a study if people know they’re being studied, they try harder at whatever the thing is, I think traditionally it was kind of factory workers and their productivity. It’s like change, different change the lighting and the factory. The workers are like, Oh, someone’s watching us and measuring what we’re doing. So we better better act. And so like, what’s the mechanism there? Well, watching surveillance essentially. So, so often, it’s really quite difficult to, to kind of split it apart, I was gonna say something else, I’ve completely forgotten what it was.

Craig Barton 55:23

It’s tricky. And it will do just just that. last final bit of and just just to dig into it practically. Let’s say for example, after our chat today, you think, right, I’m gonna go for it with this silent teacher forget Pirsch. And he doesn’t know what he’s talking about. Sound teachers is the way forward? How would you determine whether it works or not? Like, what what are you looking at? And over? What period are you looking for, for it to to get this data back?

Ollie Lovell 55:46

Your question? First, I’ll say the thing that I remembered, I was gonna say before, what I was going to say before was, this valley of latent potential is particularly prevalent, when we come back to that learning to learn or self regulated learning stuff, right? Because teaching, like there’s nothing, there are a few things quicker and more direct route in terms of getting students to high performance to high performance than highly structured instruction, where the teacher is 100% in the driver’s seat, and the students are working really hard to keep up the whole time. And they managed to keep up I think that can you know, and we see a lot of really effective explicit instruction going on. And that’s absolutely fantastic, and a really important tool for teachers to have in their toolbox. But, again, opportunity cost, if we do that 100% of the time, we miss out on a lot of the potential gains and the longer longer term benefits in particular, of creating more independent learners. But when, at the time we’re trying to make that tradition, transition, should I say we’re likely to see a significant dip in scores for extended period of time. Which brings us back to the other question, you just asked how do you know if it’s working? Or check for understanding? Check to check your understanding. But but the other part other part you asked was over kind of what period of time? And like, I don’t know, I don’t know, Craig, to me, it kind of comes back to the what comes back to it does come back to mechanisms that does it seem like the effect that you’re expecting is happening, and doesn’t seem like it’s plausible, it’s happening because of the reason that you think it’s happening. But also, a lot of teaching isn’t all quantifiable. And sometimes you have to just get a sense of things.

Craig Barton 57:41

Absolutely, absolutely. Right. So fifth and final tip, please.

Ollie Lovell 57:45

Tip number five Craig, you can learn something from everybody. Let’s start let’s start with a syllogism. syllogisms are kind of logical puzzles, if you will. I’m going to give you a few Craig. All right, this. This is the classic one. So the challenge with a syllogism is to work out if it’s valid, if the logical if the logical thread within the syllogism is valid or invalid Is that logical fallacy. So, first one, very, very famous syllogism. Socrates is a man. All men are mortal. Therefore, Socrates is mortal. Sorry, I said moral I meant to say mortal. Socrates is a man. But hopefully Socrates is mortal. And this relates to something else I was going to talk morality, something else I was going to talk about, but I think I forgot to Socrates is a man. All men are mortal. Therefore, Socrates is mortal. plays at home can listen to the home can play as long as well. Do you think that was a completely illogical conclusion? From the two statements? Talk us through your thinking, Craig?

Craig Barton 59:01

Oh, geez. Right. Okay. Socrates. Socrates is a man. That was the first one right? Okay. And all men are mortal this way. I don’t like having you on the show early because most guests I can just ask them question. I have a little sit off. Socrates is a man. All men are mortal. So it follows that Socrates is mortal. Yeah, yeah. That’s got to be complete, surely, is it?

Ollie Lovell 59:32

Socrates is a man I forgot to check the answer in the back of the book for this one. I thought I knew it. But now you’re confusing me. Socrates is a man. All men are mortal. Yeah, therefore, yeah, so it’s man. Men are mortal. Socrates is mortal. Okay, I think that’s valid. And if we’re both wrong, then shame on us and someone better writing. Alright, here’s another one for you, Craig. Oh, sorry, the pain the pain is not over. This is again for the listeners at home. for all students, natural discovery should be supported. All students natural discovery should be supported. Some inquiry based teaching should be supported. Therefore, some inquiry based teaching leads to students natural discovery.

Craig Barton 1:00:25

Now that that feels like it doesn’t quite, I’m done kind of drawing circles here with almost like a almost like a bit of a vendor, and that feels like there’s some gaps. They’re gonna say that that’s not

Ollie Lovell 1:00:35

right, let’s try to let’s try another one. All learning is a change in long term memory. Some changes to long term memory should be strengthened by testing. Therefore, something that should be strengthened by testing is learning.

Craig Barton 1:00:58

Give that to me one more time. I

Ollie Lovell 1:01:00

hope everyone is having fun as well. All learning is a change in long term memory. Yeah. Yep. Some changes to long term memory should be strengthened by testing. Yep. Therefore, something that should be strengthened by testing is learning.

Craig Barton 1:01:30

I don’t know this one only? It doesn’t it’s certainly not as tight as old Socrates. I was I was all over him. You know, I was hoping for a few more of them. I don’t I don’t know this one. The I don’t like this. This. This was something chucked in there. It’s yeah, I don’t know this one. Are you then I do you know, this one is the bigger question.

Ollie Lovell 1:01:48

I think I do I actually cross cross check this with like, a philosophy lecture at a university teaches logic. And she did. Give me the answer. If you had to take a punt totally fine. If you’re wrong, if you had to take a punt. Yeah,

Craig Barton 1:02:02

I’d say this one. See this my own bias, right. So I have a bit of long term memory and testing. I’d say this one is Yeah, it’s pretty solid. But I’m not convinced.

Ollie Lovell 1:02:13

Cool. So so this is a educational version of real study that was done by a Russian researcher, whose name I can’t pronounce, I’m not gonna try to. And it was, it was researching a thing called my site bias. And my side bias is the is our where our ability to evaluate the logic of statements or the validity of research and things like that. And the influence that our prior beliefs have on our ability to objectively evaluate things. So for you, Craig, it would be my hypothesis that you’d be more likely to classify that third, logical syllogism as valid based upon your prize and less likely to classify the the middle syllogism as valid because of your prize. The opposite would be different. For some, the opposite would be the case for someone else. It is in fact the case that both the second and third syllogisms were invalid. I’m so glad that worked. That was just like, So twist.

Craig Barton 1:03:22

Yeah, that was that was good that off? Yeah.

Ollie Lovell 1:03:26

So the point here, you know, you can learn something from everybody, what the heck do these syllogisms have? To me, one of the biggest challenges in education is our inability to listen to each other. There is something that you can learn from everybody. I just came back from a trip to the UK, I visited three schools that were the most different schools I could find. In England, I visited the self managed Learning College, which is a school with absolutely no curriculum, almost no structure, they only have structures around the kind of meeting in the morning in the afternoon, I visited XP, which does explicit instruction, but it also does expeditionary learning. And it also has a big focus on pastoral stuff. And then I visited Mikayla, which is, you know, famously the strictest school in the UK. And I learned stuff from all three of them. And it was great. But the point of these syllogisms is, if we find if we do actually find ourselves in a corner, in, you know, in a particular educational paradigm, or educational corner or something like that. And we start to associate aid ourselves and our beliefs with a certain way of thinking or a certain brand or something like that. It doesn’t only have a kind of impact in terms of who our friends are, and kind of what we choose to engage with. It also actually means that if we do say, alright, I’m actually going to have a crack and try to understand this other side of the story. Like we’re actually in capable of, of objectively analysing the facts like you just can’t get past it’s my side bias. And so, to me the only way around that the only potential way around it, because there’s probably no full way around it, the way to lessen the impact is to try to be knowledge driven, rather than belief driven. And this is a big distinction, a lot of people it’s like, it’s like, my goal is to have a bit of a have an impact, or my goal is to be a good teacher, or whatever it might be. That might be a belief driven, but if we’re knowledge of and it’s like, my goal is to truly understand the mechanisms behind this, it’s to truly understand, like whether when I check for understanding my students have lent moral or not, is to truly understand the argument of this person I disagree with, or I feel like I might disagree with that’s the only way we can start to circumvent this. What one other one other point on this. Dylan William has a great quote, which I from he said, In my podcasts, and I have it in tools for teachers, he said, The Measure of a researcher or test the measure of a researcher by asking what are two or more research results that you believe and trust, but that you do not like? I think is another great question. And he said, he said in his case, the two were the importance of IQ for educational achievement. And even more depressingly it’s heritability. And the second is cognitive load theory. He wished that problem solving was best taught through problem solving. So yeah, that’s that’s that takeaway. That’s level one of that takeaway. You can learn something from everybody. The Level Two here is that change in the world often depends upon zealots. Right? I can’t remember exactly. But I think it’s a George Bernard Shaw, quote, Tim Ferriss, pretty fond of it, you’re probably familiar with it to Craig, it’s something like the the reasonable man adapts himself to the world. The unreasonable man tries to adapt the world to Himself. So that’s one way to put it. And another way is, you know, often the people who create these interesting schools like the reason why Mikayla exists. And the reason why they’re self managed Learning College exists, is because there are people out there who have such conviction about their beliefs, that they’re willing to put everything on the line, reputation, finances, family relationships, to actually create something in line with those beliefs. And if everyone was was, you know, pontificating about what the what the honest, what the true answer to everything is, we probably wouldn’t end up with these phenomenal schools that take completely different directions, but that actually help us to have a clearer understanding of what works, or more importantly, what works for whom, under what circumstances for what purpose, how and compared to what to quote, Adrienne Simpson, and add a little bit as well. So, you know, being Nigerian is great. Being belief driven is great as well. Everybody wins. But most importantly, you can learn something for everyone.

Craig Barton 1:08:12

Great that Oh, that’s fantastic. One reflection, one question. So first themes, I always like that mantra, find someone smart, who you disagree with, I was like that, like find real smart people who have the alternative view and just try and listen to them. So there’s got to be some some basis to that. So I like that. And my second question is to be my final question for you all. And you mentioned those three schools give just give me just just one takeaway from each something that you learn from from each that maybe either surprised you or has influenced your practice. Sure.

Ollie Lovell 1:08:40

Okay. Self Managed Learning College. A belief in students in a in a young person’s ability to to self govern, and like unfaltering belief in that can actually unlock phenomenal things in young people.

Craig Barton 1:09:02

That’s just what age with these kids are, they

Ollie Lovell 1:09:04

were I think it’s like nine to 16.

Craig Barton 1:09:08

Wow, okay. That’s good. Yeah, I’d love to see that. That’s great.

Ollie Lovell 1:09:11

It’s pretty interesting place XP. Or XP. It’s just like, if if you get relationships, right, so much else follows. Some would say everything else follows but so much follows when you get there. Right. And Mikayla? You don’t know what high standards are until you’ve been to Macau. Have you been there?

Craig Barton 1:09:38

Not yet. No, I can’t wait.

Ollie Lovell 1:09:41

This is absolutely madness. So yeah.

Craig Barton 1:09:46

That was brilliant. That’s brilliant. Well, they were five absolutely fantastic tips. So let me let me hand over to you what should listeners be checking out of yours and I’ll put links to these in the show notes as

Ollie Lovell 1:09:55

well. I’d love it if, if listeners checked out the education research Freedom podcast. See if lots of fun on there. So much fun. I had you on there twice Craig. I’ve recently done it, people have seemed to enjoy Cognitive Load Theory in action as a concise and actionable guide to cognitive load theory. If people are keen to go deeper, I have recently released an online course that you can find them on my site on called Cognitive Load Theory mastery. We’ve had a few people complete that that one now even though it’s only been up for a couple of weeks, and had some really, really positive feedback. tools for teachers is another book. That’s, that’s out now. And it’s now even been used in some kind of university initial teacher education courses. And so that’s really encouraging that people are finding enough value in that. But apart from that, just remember you can learn something from everybody.

Craig Barton 1:10:44

That’s lovely that just final thing for me I just two episodes of yours that I read well while I revisited and while I listen to for the first time, so I love your your dog love interviews, fantastic. I love I love the structure that you do it that way you give yourself a little time to get through. And he really embraces that as well. That’s really good. And what what I liked, I like dogs must have been interviewed 1000s of times, right? And he’s probably been asked the same questions. But he really warm to that structure that that challenge of having to be concise, and he got through so much practical stuff from us, I thought it was a wonderful episode. One of the things I’m trying to do at the moment is, instead of consuming new content, make sure I revisit content that I’ve got something out of in the past, just with this old classic speak to your condition because you probably take something new from it and so on. And that was a definite example of that. But particularly when he talks about paired work and stopping paired work almost too soon riding this crest of the wave because you don’t want it to kind of fizzle out things like that I thought was a wonderful interview. And then you’ll have to forgive me because I’ve forgotten the name of the guy but you alluded to early on that the science teacher guy you had on hold. What was his name? I’ll

Ollie Lovell 1:11:49

post Bensley.

Craig Barton 1:11:51

Yeah, he was good. Hey, he was good. He was good. I really really enjoyed that aback and formative assessment and stuff so I’ll put links to both of those in the show notes because they were great. Wow well this is always been a pleasure speaking to you I got I always give a little behind the curtain appearance here so you’ve got last time we were on the podcast I think you put your name as the best podcast or something like that. Today you’ve got the original t for t creator So what are these claiming here listeners is because he’s got tools for teachers and I’m tips for teachers that there’s some kind of legal battle could ensue here but yeah, I’ll I’ll he was the first with the t for t but we’ll see. We’ll see what happens in the long term.

Ollie Lovell 1:12:27

I think I think last time the last time you came on with the the original podcaster I think I should I just wanted to come back at you with the T 51.

Craig Barton 1:12:37

Well, only novel airs or is always a pleasure. Thanks so much for joining us today. Thanks, Craig. It’s always fun.