***You can purchase a book on Diagnostic Questions in paperback or on Kindle, or a 90-minute online workshop that you can share with colleagues at a CPD event or departmental meeting here***

Multiple-choice diagnostic questions are one of my favourite ways to check for understanding. I love them so much that I first built a website to house them called DiagnsoticQuestions.com. Then, I co-founded an assessment platform built on them called Eedi.

- Diagnosis

- Evidence

- Solution steps

- Use case 1: Challenge students to get a diagnostic question correct

- Use case 2: Challenge students first to answer the question without the choice of answers

- Use case 3: Challenge students to explain the wrong answers to a diagnostic question

- Use case 4: Challenge students to make the wrong answers correct

- Use case 5: Challenge students to generate the wrong answers to a diagnostic question

- Use case 6: Challenge students to create their own diagnostic question

- Use case 7: Challenge students to reverse engineer a question

- Want to know more?

- Implementation planning

- Book and 90-minute online workshop

Diagnosis

- What role do multiple-choice questions play in your teaching?

- What is your process for asking them and collecting students’ responses?

- How do you respond to the data?

Evidence

What is a diagnostic question?

All the multiple-choice questions I write have the same structure: one correct answer and three wrong answers – known as distractors – each designed to reveal a specific mistake or misconception.

Of course, there are other types of multiple-choice diagnostic questions, such as those with more wrong answers, multiple correct answers, or those where the correct answer is subjective. These may be more suited to different subjects.

In this section, I will focus on the structure of the diagnostic questions I use. So, feel free to adapt my strategies accordingly.

What things can diagnostic questions assess?

Broadly speaking, diagnostic questions can assess three different aspects of understanding.

1. Factual recall

Can students recall a fact or relationship?

2. Procedural

Can students correctly carry out a given procedure?

3. Conceptual

How secure is students’ conceptual understanding?

Why are multiple-choice diagnostic questions a good way to check students’ understanding?

There are several reasons:

- We quickly see the responses of all our students. This gives us a more reliable sense of our class’s understanding than if we relied on one or two students who volunteer or who we Cold Call. It is also a more efficient way to get a sense of our students’ understanding than if we relied on circulation. Finally, we see responses from all our students without having to hand out equipment such as mini-whiteboards, opens and rubbers, which are prone to misuse. This paper is good on the efficiency of diagnostic questions.

- Wrong answers are interpretable. Good diagnostic questions have targeted distractors – in other words, incorrect answers designed to reveal a specific misunderstanding or misconception. Hence, if a student gets a multiple-choice diagnosis question wrong, we immediately know why without spending time and attention in a busy classroom trying to figure it out, as with open-response questions. This also means teachers can plan for error – looking at distractors in advance, figuring out why a student might choose them, and planning how they will respond if they do. This paper is good on the interpretability of distractors.

- We can use questions to assess specific concepts. Because multiple-choice diagnostic questions are quick to ask and gather data on, teachers can ask several quickly. So, we can choose several questions, each targeting a specific skill rather than asking one broad question. This supports the interpretability of the wrong answers and broadens the range of concepts students are asked to retrieve, thus strengthening their memories. Again, this paper is good on the specificity of diagnostic questions.

- Multiple-choice questions can be more cognitively challenging than open-response questions. Whilst it may seem that multiple-choice questions are easier than open-response questions because students can guess the answer or pick up on cues as to what the correct answer is, a well-constructed multiple-choice question, with plausible and well-designed distractors, can be more challenging than an open-ended question because it forces students to engage in a process of active evaluation, reasoning and retrieval and to avoid the lure of the distractors in their quest to get the question correct. This paper is good on this often-overlooked point.

- We can do interesting things with the distractors. My mantra is: Thinking does not need to stop with the correct answer. Once we have established the correct answer, we can turn our attention to the distractors, challenging students to consider why others may choose them or even create their own distractors.

When might teachers use a multiple-choice diagnostic question?

Multiple-choice diagnostic questions are flexible in their use. Here are a few times you might choose to use a diagnostic question to assess your students’ understanding:

- During a spaced retrieval Do Now. We could start our lesson with, say, four diagnostic questions based on concepts students have encountered in the past to reduce the chances of them forgetting.

- To assess relevant prior knowledge. We are about to teach a new idea and so use some diagnostic questions to ensure the foundations are secure.

- Following an explanation. After a teacher-led model, we can ask a diagnostic question to see how much our students have picked up before we set them off on consolidation work.

- As a hinge point. Partway through a lesson, we can ask a diagnostic question to see if our students’ understanding is secure enough for us to move on to the next phase or whether they need more time and support.

- As an Exit Ticket, at the end of a lesson, we could ask a diagnostic question to gauge our students’ progress and inform us of where the next lesson should start.

- In a homework or Low-Stakes Quiz. We may use diagnostic questions in written assessments as an alternative to open-response questions.

What makes a good multiple-choice diagnostic question?

Not all diagnostic questions are created equally. Much research (see this paper and this paper in particular) has been done into what makes a good multiple-choice diagnostic question.

Here are the four things I consider when writing or selecting diagnostic questions:

- Each distractor should be plausible and reveal the specific nature of a child’s misunderstanding (see below for a distractor deep-dive!).

- There should be no ambiguity in either the question or the answers

- The question should not require several steps to arrive at the answer as it is hard to write distractors to identify where the misconception lies

- It should not be possible to get the question correct for the wrong reasons

Here are some examples of diagnostic questions that break these rules:

The intended correct answer is B. But C is also correct.

With no markings on the diagrams, you could argue none of the answers is correct. But assuming we are to go by inspection, A, B and C are valid answers.

A student could get the correct answer of 4 by working out the mean or the median.

None of the calculations gives the correct answer apart from A. So, what is the question assessing? Can students work out addition problems or interpret what numbers need to be added?

More general guidance comes from this paper about constructing written test questions for the basic and clinical sciences:

Distractor deep-dive

The quality of the wrong answers – the distractors – makes or breaks the multiple-choice diagnostic question. My principle of: Each distractor should be plausible and reveal the specific nature of a child’s misunderstanding, encompasses many subtleties. There are swathes of research on the quality of distractors – this paper, this paper and this paper are good starting points. If you really want to geek out on it, here are some findings from research relating to multiple-choice distractors:

- Item Difficulty: Distractors directly influence the difficulty of a question. Well-written distractors that are plausible make a question more difficult because they require students to engage in effortful retrieval of the correct answer from memory, rather than simply recognizing it among obviously incorrect options. Conversely, if distractors are not plausible, students can easily rule them out, increasing their chances of guessing the correct answer.

- Item Discrimination: Distractors should be selected more often by low-performing students than high-performing ones. Effective distractors help differentiate between students with different levels of understanding. If a distractor is chosen equally by both high and low-performing students, or if it is not chosen at all, it does not effectively contribute to the item’s ability to discriminate.

- Question Reliability: The reliability of a question can be affected by the quality of the distractors. If distractors are not functioning well, meaning they are not plausible or are not chosen by students, then the question may not be accurately measuring the knowledge of the students. The probability of randomly selecting the correct option decreases as the number of options increases, but only if the distractors are plausible. If the distractors are not plausible, adding more options will not improve reliability.

- Student Learning: Distractors can influence learning outcomes. When distractors are plausible and share important information with the correct answer, they can elicit beneficial retrieval processes that improve memory retention. However, if distractors are unrelated to the correct answer, they can introduce misinformation, thereby decreasing memory retention. The number of unrelated distractors can also adversely affect memory retention.

- Diagnostic Information: Distractors can provide diagnostic information about students’ problem-solving skills and misconceptions. If distractors are developed based on common student errors, they can help teachers identify specific areas where students are struggling and adjust instruction. This also allows a teacher to target instruction more effectively.

- Test Security: The position of the correct answer relative to the distractors can influence the difficulty of items. Randomizing the position of distractors can reduce the possibility of cheating and improve question security.

- Test Wiseness: Item writing flaws related to distractors (such as grammatical cues, inconsistent language, or illogical options) can make it easier for test-wise students to guess the correct answer, regardless of their understanding of the content. These flaws undermine the validity of the test.

- Number of Options: The number of distractors impacts test quality. While more options might seem better at reducing guessing, research suggests that using two distractors (for a total of three options) is often optimal. It can be challenging for content specialists to create three or more distractors that are highly plausible but still incorrect, and that may lead to the inclusion of ineffective or implausible distractors.

In summary, distractors are not just filler; they are integral to the quality of a multiple-choice question. They influence item difficulty and discrimination, contribute to diagnostic information, and affect the reliability and validity of the data gathered. Well-designed distractors are plausible, based on common misconceptions, and help to differentiate between high- and low-performing students. Poorly designed distractors can lead to inaccurate assessments, student confusion, and reduced learning. Therefore, careful attention to distractor development and analysis is essential for creating high-quality multiple-choice tests.

Solution steps

Once we have selected or written a good diagnostic question, and chosen an appropriate time in our lesson to use it, the next challenge is to consider how to use it.

Use case 1: Challenge students to get a diagnostic question correct

This is by far and away the most common use case, so it needs special attention.

Routines

I am a great believer in the power of habits and routines. Here is the routine I teach my students for answering diagnostic questions, along with the justifications for each step:

- Think in silence… so you can fully concentrate

- You can do working out if you like… to help organise your thoughts

- Think about the answer and rehearse how you would explain it… so you are ready to share with the class

- Don’t look at anyone else’s working… as I want to know what you think so I can help you if needed (everyone needs help sometimes)

- Only show your me your answer when I ask… so everyone has a chance to think for themselves

That middle step – rehearsal – is a key one. If you don’t include that as part of the routine, two problems emerge:

- When you call upon a student to explain their thing, they haven’t prepared and so do a lot of summing and ahhing as time ticks by

- The only students who think hard about how they would explain their reasoning are the ones you call upon.

Thinking time

This will depend on the complexity of the question, but generally speaking, the thinking time for most diagnostic questions I ask in maths is:

- Between 5 to 10 seconds to think of the answer

- About 10 seconds to internally rehearse the explanation

- TOTAL ≈ 20 seconds per question

Again, step 2 is the key here. If this routine is new to students, I will explicitly remind them to do their rehearsal after the first 10 seconds or so of thinking time.

Seeing the responses of all our students

Seeing the responses of all our students is one of my key principles for checking for understanding, and one of the main reasons I like using diagnostic questions.

Here are some options:

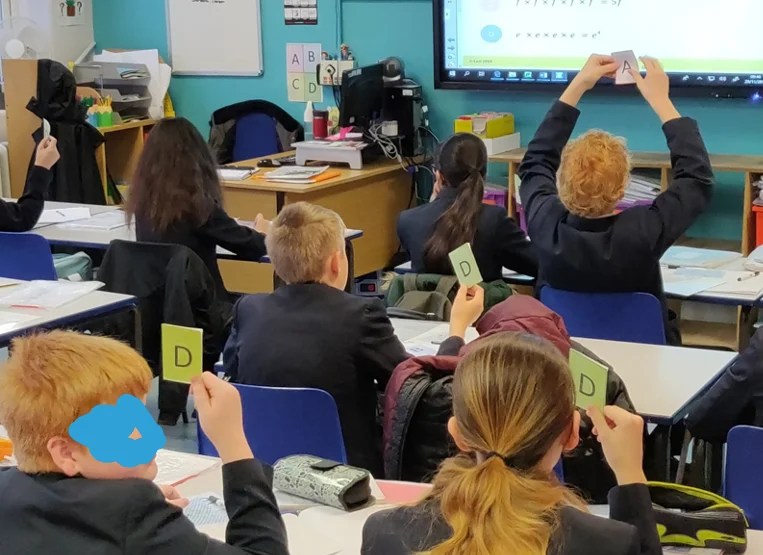

1. ABCD cards

These come in a variety of formats. Make sure the letters are coloured differently to distinguish between student choices in a large class easily.

An alternative to handing out ABCD cards is to stick them to books and ask students to orientate their book to indicate their choice:

2. Use mini-whiteboards

Mini-whiteboards have the advantage that students can also do their working out on them. But they have the disadvantage that it can be hard to see students’ answers:

So, if using mini-whiteboards, be clear how you want students to display their answers, or they will choose themselves:

3. Use fingers

Students may forget their homework or their exercise book, but they rarely forget to bring their fingers to class. Hence, you can quickly check for understanding without the need to give out any equipment by asking students to raise one finger for A, two for B, and so on.

Voting on fingers has a few issues, though! First, distinguishing between students’ choice of answers can be tricky. Second, it is very easy for a student to switch their answer. Third, some students have been known to display rather less than appropriate gestures on their fingers, like this football crowd whom I can only presume are voting A to a diagnostic question:

4. Use technology

There’s a wonderful world of technology for collecting student responses in class. Plickers is probably the most well-known.

Three things to be aware of if using technology in this way:

- Technology issues – whether they be hardware, software, or wifi. Is this a barrier for you?

- Time – does using the technology save you time versus something like ABCD cards? If not, what extra benefit is it bringing you?

- The message – as soon as students are aware that their answers are being recorded somewhere, the incentive to cheat or opt-out increases. How will you counteract this?

5. Heads down

Here is science teacher and podcast guest, Pritesh Raichura, getting his students to respond to a diagnostic question:

Here are three benefits of collecting responses in this way:

- You don’t need to give out any equipment

- It reduces the flow of information for the teacher

- It is much harder for students to copy each other

How to respond?

Once we have seen the answers of all your students, we need to respond. Here, I use my model of responsive teaching, focussing on three broad scenarios:

If we find ourselves in the middle scenario where some students know the answer and others do not, it is important to ask students to explain the reasons behind their choices. This can happen during a turn-and-talk or via Warm Call. Students giving explanations helps develop their verbal reasoning and allows you to diagnose whether students are guessing or if their understanding is secure.

Make sure students know the correct answer

However, you choose to res[ond, make sure at the end of it that students are aware of what the correct answer is. This is always important following a check for understanding, but particularly so in the case of multiple-choice diagnostic questions where you will likely have spent time discussing and thinking about the wrong answers.

Research suggests that feedback can reduce the likelihood of students remembering the wrong answers. That feedback does not have to be written. The authors recommend: an indication of accuracy (correct/incorrect), a re-presentation of the question, the response the student selected, and the correct response.

This can be achieved in the classroom by physically crossing out the wrong answers and/or circling the correct answer.

Two extra checks for understanding

Two extra checks for understanding you can quickly ask when you have seen your students’ responses are:

1. Ask students to write their reasons. Mini-whiteboards are good for this, and the answers can often be revealing:

2. And now tell me… Give students a follow-up question based on the question they have just answered.

For example, this teacher asked their students to give two features of the perpendicular bisector that they have just correctly identified:

Use case 2: Challenge students first to answer the question without the choice of answers

Research suggests that asking students to guess the answer before showing them the options improves memory and recall. The participants in the study were challenged to translate words, so there is no guarantee that the same effect transfers to mathematics or any other domain, but it is worth a go. We hope to research this on our Eedi platform in the future

Use case 3: Challenge students to explain the wrong answers to a diagnostic question

I have a mantra regarding diagnostic questions: Thinking doesn’t need to stop with the correct answer. Sure, students can explain why B is the correct answer. But can they explain why someone else might think D is the correct answer? Furthermore, how would they convince that person that their answer is wrong?

This is a good challenge to give to a group of students whilst you support the rest of the class (they can then compare their answers with another student who is working on the same task), or to give to everyone if they get the initial question correct.

Use case 4: Challenge students to make the wrong answers correct

This one works particularly well in maths. Once we have established that the correct answer is B, we can again focus on the incorrect answers. This time, the challenge is to change the question as little as possible to correct one of the incorrect answers. As little as possible is the key. It taps into one of the key principles of variation theory, changing one key element, holding everything else the same, and observing its impact on the solution.

So, how little can students change the question so C is the correct answer? Some may go for What is 10 times 43? Others may opt for What is 10 more than 420. Again, this can be a worthy challenge for a group of students or the whole class.

Use case 5: Challenge students to generate the wrong answers to a diagnostic question

Here, we can use the Derring Effect, whereby deliberately committing errors even when one already knows the correct answers produces superior learning than avoiding them, particularly when one’s errors are corrected.

So, we can present students with the question without the four possible answers and ask students to generate plausible wrong answers for the question (alongside the correct answer). Students can swap answers with their partners and explain their reasoning. Then, the big reveal can come when we show students the original choice of answers.

Use case 6: Challenge students to create their own diagnostic question

This is a step up in challenge from the previous option. Students must generate a question, the correct answer, plausible wrong answers, and reasons for those answers. This makes a fantastic Exit Ticket, homework assignment, or assessment question, allowing students to demonstrate the depth of their understanding.

Use case 7: Challenge students to reverse engineer a question

This is a fun one. You tell students the topic – in this case mental addition – show them the four answers, indicate the correct one, and challenge them to think what the original question was. Again, they can swap ideas and justifications with their partner before the big reveal.

Want to know more?

For thousands of maths multiple-choice questions, check out our Eedi Quiz page, and for questions for all other subjects, check out diagnosticquestions.com.

Implementation planning

Here are the different ways of using diagnostic questions we have discussed:

- Answer the question correctly

- Answer the question without the choice of answers

- Explain the wrong answers

- Change the question

- Generate the wrong answers to a diagnostic question

- Create your own diagnostic question

- Reverse engineer the question

Use these ideas to complete the prioritisation exercise here.

Book and 90-minute online workshop

***You can purchase a book on Diagnostic Questions in paperback or on Kindle, or a 90-minute online workshop that you can share with colleagues at a CPD event or departmental meeting here***